This is an extended version of a blog originally posted with UK in a Changing Europe by Simon Usherwood and David Moloney.

The conclusion of the Windsor Framework has rightly been taken as a moment for UK-EU relations to reset. As part of that, belated notice has fallen on the review clause of the Trade & Cooperation Agreement (TCA). The provision sets up five-yearly reviews of this cornerstone treaty between the two parties and has been seen by some in the UK as a place to engage in wholesale renegotiation of relations. By contrast, the EU is pointing towards a much more technical exercise, while others still point to the potential for further tensions.

We argue here that given the vagueness of the provision, what actually happens is primarily a function of what the two parties decide to make of it and as a result there is much still to be settled. If the review is to produce anything of substance, then both Brussels and London need to agree on a process and a realistic set of objectives.

The context

Article 776 of the TCA is short and to the point:

“The Parties shall jointly review the implementation of this Agreement and supplementing agreements and any matters related thereto five years after the entry into force of this Agreement and every five years thereafter.”

It’s a provision that can be found in a number of other agreements concluded by the EU in recent years, such as with New Zealand on data exchange for law enforcement or with the US on Passenger Name Records. It differs from provisional application provisions (like for the EU-Canada trade deal) that were historically more common in that the agreement is in full effect and there’s no explicit mention of having to pass a hurdle to move to a permanent arrangement. As such, it’s also not quite the same as the six-yearly review in the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement, where specific options are listed, including deciding to terminate it all.

Notably, international law on treaties is silent on such reviews. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which is the standard benchmark in such matters, sets out how contracting parties can invalidate, terminate, withdraw from or suspend a treaty, but leaves it to case-by-case choices on reviews.

Instead, it’s best understood as a primarily technical process, largely reflecting the increasingly technical nature of provisions and the need for the joining up of numerous national systems and processes. Note that it speaks about reviewing the ‘implementation’, rather than the TCA itself. The terse and generic formulation does not explicitly engage any of the numerous bodies created by the TCA nor require any formal approval or even acknowledgement by the two parties.

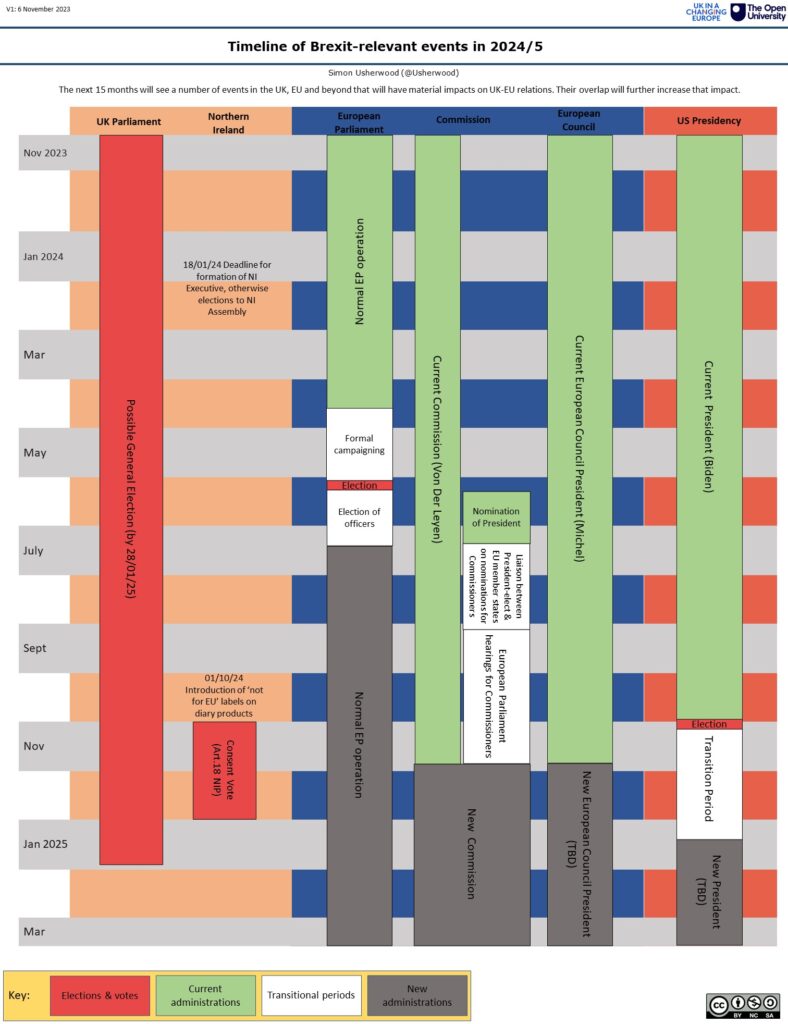

Indeed, this is best underlined by the question of timing. While many in the UK have suggested that the five year period would be concluded by 30 December 2025 or 1 May 2026 (five years since the provisional or full application respectively), the EU has more recently suggested that the latter date would be the start of any review. Given that the UK has not pushed back on this, the latter timetable is more than likely to prevail, especially since various parts of the TCA have still yet to come into effect.

However, a technical process does not preclude political engagement alongside it. None of the other cases mentioned have covered nearly so much as the TCA does, nor were any of them produced under such pressure of time and politicisation. Which is to suggest that there are three logical paths that might be followed from 2025 into 2026.

Three pathways

The minimalist model is the most obvious, given the comments just made. If it followed the pattern of other agreements, the two parties would engage in no more than a technical check on implementation, underpinned by reports from the various sectoral committees, with a view to addressing any emergent issues and to refining processes.

This approach would be kept away from politicians, except in some final approval through the TCA’s Partnership Council, possibly accompanied by some declarations about actions to attend to whatever procedural or bureaucratic barriers inhibit the implementation of the treaty as it stands.

The attraction here is that it fits closely with much of modern international treaty management: no new negotiations or big political displays to coordinate, just technocratic optimisation by the people actually doing the work. If we assume that any new agreements – within or outside the TCA itself – would run on their own timetable, then this periodic check helps ensure more general ticking over of the machinery, albeit without offering an opportunity for more structural reform.

Such reform is however one of the major reasons the review is now receiving attention in the UK. The possibility of a new Labour government from the next general election has prompted calls for a root-and-branch recasting of relations. The review might, in this maximalist view, become the moment on which that turns.

The May 2026 start would come some 18 months into a new UK government, giving them time to organise themselves around a new mandate and to get going on the rest of their manifesto programme. With some practical demonstration of British good faith and a clearer picture of how an opposition Conservative party moves on the issue, the EU might be persuaded that the TCA review be rolled into a wider reconsideration of relations.

This would require both sides to establish specific mandates to negotiate. In the EU’s case, that would need the approval of member states and widespread consultation. If the ambition were to stretch to discussing participation in the EU’s single market, then the status and operation of the Northern Ireland Protocol could also come under inspection, meaning London would have to work closely with Belfast, where the (non-)existence of the Executive might become yet more relevant.

Such procedural hurdles are matched by the political risks. The EU knows well from the failed decade of negotiations with the Swiss over recasting their relations that even where there are clear logics of organisation or of trade, this does not automatically produce mutually-acceptable outcomes. The memory of the negotiations with the UK of both the Withdrawal Agreement and the TCA itself will also linger long in Brussels, where it was noted that these were difficult not only because of the Prime Minister but also because the UK has its own interests and preferences. To take a more recent example of this, talks on rejoining the EU’s Horizon research programme – flagged as an easy win back at the signing of the Windsor Framework this spring – have become bogged down in questions of finance.

If neither a very limited nor a full-on approach feel satisfactory, then a mixed model might seem to square the circle.

Rather than starting with an explicit intention of recasting relations, the framing would instead be one of a desire for broad reflection on how the UK and EU work together. Here the TCA review would become part of the evaluation of what does and doesn’t work and what might be the steps to address that. The door would be left open to negotiations or treaty amendments, but pushed down the line.

2025 and 2026 would therefore see increased contact between the parties, at both political and technical levels, with joint working groups drawing in consultation from relevant groups to produce options for consideration. By removing any initial obligation to particular outcomes, this might encourage engagement from a wider range of participants and improve the chances of producing more stable and resilient systems.

However, that same flexibility and open-ended approach risks creating a permanent instability, where each side speaks of wanting to improve things but without both being able to agree on how to do it. With the constant cycle of national elections in EU member states, quite aside from the vagaries of British politics, the lack of ability to be confident about holding a consensus long enough to translate it into a firm commitment of some kind points to potentially destabilising a relationship that has only just started to find its feet.

What matters

Ultimately, the review clause is an empty vessel, waiting to be used as the UK and EU see best, so far as they can agree on what that actually means. Unless and until they achieve a consensus on an approach, then even the minimalist model might look over-articulated.

So what will determine whether and how the two sides find a common understanding?

Firstly, the position of whatever British government is in office will be crucial. Is there a clear and reasonable strategy behind its European policy? Is it ready to invest sufficient political capital on an issue that most voters aren’t that interested in to overcome any domestic opposition, including from those on the other side of the Commons? If there is any doubt in EU minds on these points, then there is very little interest in doing anything more than the bare minimum.

Secondly, the EU itself matters. While the post-Brexit period has seen a big push towards strengthening international trade partnerships and while the invasion of Ukraine has stimulated cooperation on security, that might not still be the case in 2026, especially if all of the obvious actions have already been taken. Member states have many other policy priorities to work on, so is a return to working with the UK important enough to merit the effort?

And finally, we have to consider the TCA itself. At this stage, it is impossible to make a balanced judgement about its operation, especially given that various parts of it have yet to start operating at all. If the next three years end up with a piling up of problems (as we are starting to see with rules of origin on car batteries, for example) then pressure for a more involved review might build. Conversely, as market operators and politicians adjust to the much calmer post-Johnson world of working together, a low-key approach may prevail.

However it plays out, the bigger message is that it’s only by working together that the two are going to be able to make mutually-acceptable and durable decisions.