A bit of tricky one, this. It partly explains the hiatus in posting of late, although that might also be down to the rubbish weather.

As we move towards a General Election, interest has naturally turned towards what a Labour government might look like and do. And EU policy is a recurring question.

On the one hand, the party played down the issue. It’s not that salient among voters; the party worries its views might dissuade swing voters; and the Conservatives will make full use of an ‘will of the people’ argument on any big changes in relations.

On the other, the relatively distant trading relationship with the EU is a deadweight cost to the economy, instinctive sympathies for close relations exist throughout the party leadership and there’s an incentive to demonstrate how to ‘make Brexit work’ is more than just about tone.

Which leaves observers in a position of some uncertainty.

I have yet to speak to anyone who thinks there is a more developed and ambitious EU policy within the party, awaiting the moment it can be unleashed, presumably after a crushing election victory.

At the same time, the piecemeal and hopeful approach of what we already know appears to be not fully fit for any constructive purpose. As Tim Shipman noted last week, it’s not enough to say that you’re not the Tories and hope everything falls into your lap. Both the EU and its member states have already secured their key objectives in the TCA/WA treaties, so the UK needs to have a more compelling sell if changes are to ensue.

All of which is a prelude to a graphic-in-progress.

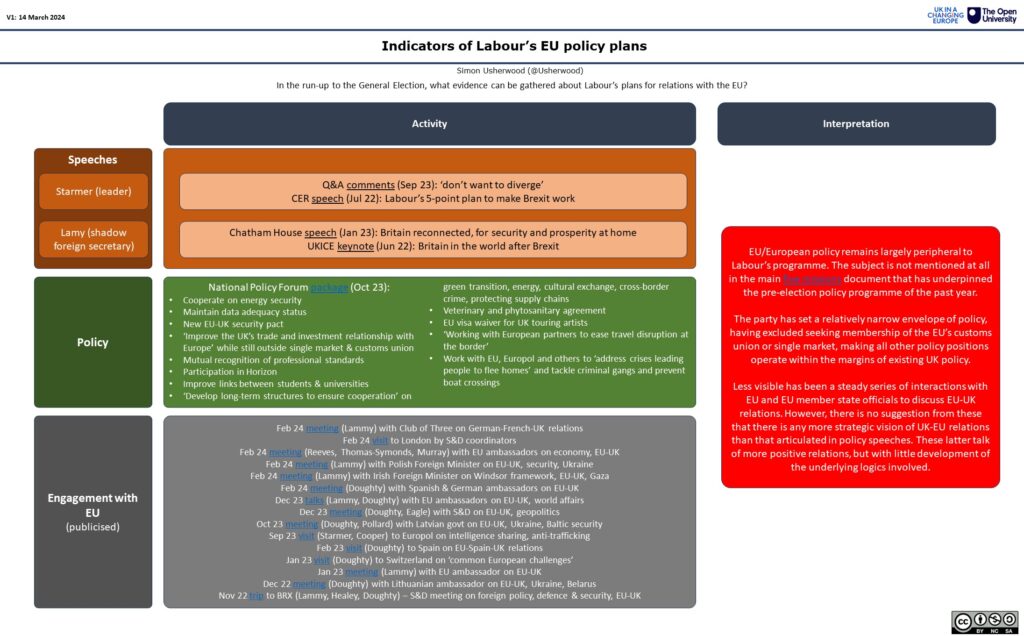

Here I’ve try to gather all the public elements of Labour’s EU work in the post-Johnson period. That includes speeches substantively about the subject (although all of these drift off into broader framings to various degrees), policy statements and interactions with relevant people.

It’s a limited overview, since there are various other things going on that I’m aware of, but can’t easily substantiate. However, there’s nothing that suggests any significant divergence from the broad picture presented here: lots of getting-to-know-yous, warm words, but minimal policy development beyond that.

At a guess, the intention is to get a few (relatively) simple wins – on SPS, on security – and then to leave more involved options for the fabled second term. Of course, those more involved options are also the ones that need more time to negotiate, so whether anything significant could be wrapped up in time is a moot point right now.

But that is to miss the wider point, namely that while there is an agenda of strengthening the UK’s profile as a key partner, within which EU relations sit, the starting point is one of minimising spending of political capital, rather than a strategically-grounded reassessment.

That’s understandable from a political management perspective, but it runs the risk of leaving a Labour government underpreparing for handling any future bumps in the road, foreseen and unforeseen. Just as the Major government found that reactive European policy had its limits in the 1990s, so too might Starmer discover that leaning-in is the less politically-costly option in the long run.