Maybe it’s the sense of the passing of the seasons and the proximity of the next British general election, but recently I’ve been asked a lot about whether a Labour government would make a bold move on EU relations.

Mujtaba Rahman has obviously also been finding this, with his report today about various member states being up for flexing to get the UK much closer in the wake of the war in Ukraine:

If I’m hesitant about the degree to which the EU might actually bend single market arrangements after making so much of cherry-picking, and about how widespread such views are, the simple fact that this is even being discussed points to the potential for fluidity in relations.

That said, what the EU wants/might accept is far from the only variable. Not much of postwar European policy really makes sense without considering the domestic political constraints and incentives in the UK itself.

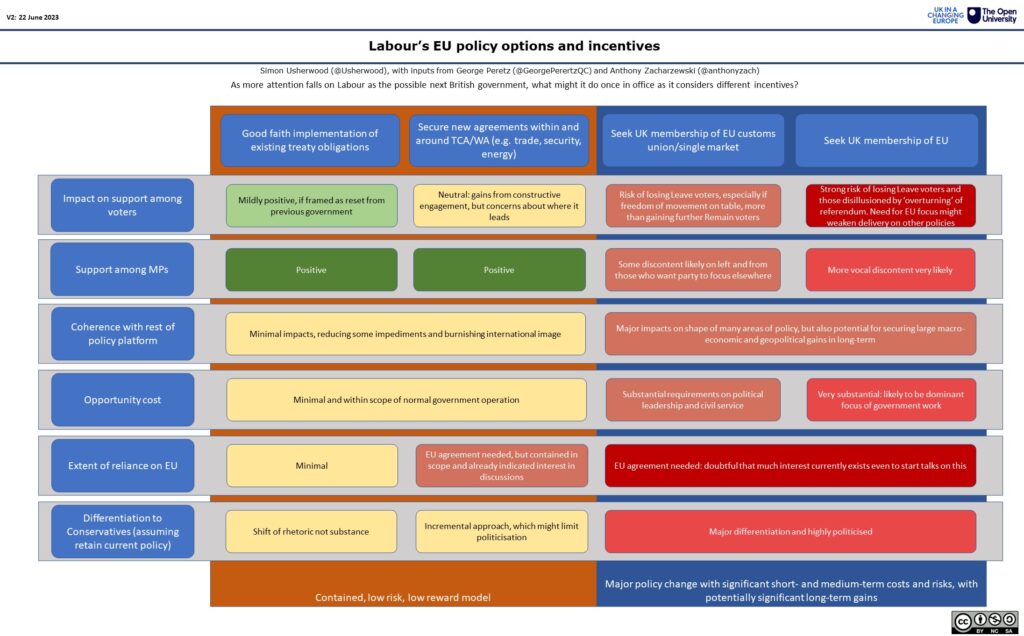

With that in mind, I have been turned over this problem for a while to produce the graphic below.

Factors

I’m assuming here that political parties are shaped by a number of factors. First there is ideology, but if we accept that centrist left thinking has never quite settled on whether internationalism is compatible with national solidarity then I don’t think this is much of a factor here, so I omit it.

What can’t be left out is voter support. Labour has been assiduous in targeting those things that have lost it votes (e.g. Corbyn and the radical left) and those things that might win it votes (e.g. competence in economic management). That’s worked really well, even if aided by late-stage Tory rule, so any EU choice needs to be seen in that light.

Let’s note Labour is already home to most Remain voters and has built up its recent success on the back of attracting Leavers from the Tories, all while not really talking about the EU at all (see Kelly Beaver’s presentation to the recent EU-UK Forum conference for more).

Even if the salience of things European has dropped markedly, there has to be some concern that a move to a major reworking of relations (i.e. either single market membership or rejoining) under a new government will cause some of those Leavers to reconsider their support, more than might be offset by the tapping into people’s clear frustrations over the situation right now.

Internal party cohesion also matters. As any Labour leader can’t fail to have noticed by looking across the aisle, ‘Europe’ can be a highly divisive force within a party. Even if Labour isn’t quite as exposed as the Tories were during the last 20 years, there are clearly a range of positions on European integration and the UK’s relationship with it.

Part of the peace on this recently has been exactly because the leadership hasn’t pushed a radical line. If that changed then we’d expect to see some MPs break on that, especially if the Commons majority is small; in that, the legacy of Spartan ERG rebellions by MPs utterly unwilling to bend to their leader’s will is likely to live on.

We also have to remember that parties have more than one policy. This carries two main implications.

Because European policy is cross-cutting, changing basic trading and political relations with the EU would come with implications for the rest of the policy platform. Trade policy with the rest of the world is an obvious example, but recasting economic links with the single market would also affect the government’s ability to pursue unilateral state aid or public procurement. Business would face another uncertain transitional period to any new arrangements, weakening or delaying investment choices, which in turn might cause short-run negative impacts, even if they ultimately unlocked longer-term benefits. As we know from recent history, a weaker economy also affects tax income, monetary policy and the overall pursuit of government objections.

Moreover, that cross-cutting nature of EU policy also means that moving beyond the TCA framework risks generating significant opportunity costs. As we’ve seen with Brexit, EU rules have been deeply intertwined with domestic processes and structures, and returning to significantly closer relations will carry a need to rebuild that. This then requires a diversion of political and bureaucratic capital that could otherwise be used for pursuing other policy goals (and ones that voters consider more important, let’s not forget).

While we might note that governments regularly walk and chew gum at the same time, the experience of 2016-19 should also point to the potential for the EU to become an all-consuming issue.

In all this, the EU itself matters. As we noted at the top, while there might be a variety of views among member states, anything that goes beyond just implementing the current treaties requires the EU’s explicit approval. That might be relatively easy for things like refinements to the TCA, such as a veterinary agreement or work on energy cooperation. But as the ongoing impasse on Horizon membership shows, even this level of work can be tricky.

But moving to readmitting the UK to single market institutions, let alone full re-accession, carries big questions for the EU. Partly that’s about a concern of whether this second volte-face is going to last any longer than the one that led to the 2016 referendum, but partly it’s also about whether the EU feels it needs the UK in general. The Union’s ability to progress on several policy fronts in the last three years and extent to which some member states have improved their profile in that time reflect how the UK would not be coming back to the same organisation it left.

And finally, there’s a dollop of good old party politics. Here I’ve focused only on differentiation to the Tories, since they would be the main opposition to a Labour government. Even on a conservative [sic] assumption that there wasn’t a shift to a more radically sceptical EU policy in such an event, we would expect there to be an effort to continue portraying Labour as European lapdogs, whatever they do.

If policy swung towards a more full-on shift to closer links, then the Conservatives will be more than happy to jump on that and make a ‘will of the people’-style argument to try and tar the entire Labour programme. Of course, if the Tories did that in an extreme way, under a ultra-hard Brexiteer, then that might help Labour narratives about how the opposition have lost the plot, but it still comes back to the opportunity cost point above; the more you spend time and effort on this, the less you have for other stuff.

I’ll note in passing that a more radical sell on the EU might be beneficial to Labour in covering any similar effort by the Liberal Democrats. However, even here we might note that the LibDems seem to have reverted to their 1980s/1990s approach of hyper-localism, coupled to passive internationalism, instead of pressing on with the very vocal pro-Europeanism of 2017-19.

Policy options

So overall, what we have are a range of factors, against which I’ve mapped four policy choices, ranged from ‘steady as she goes’ to full-on re-accession.

All of this seems to me to point to only two viable paths for Labour to follow at this juncture.

The first is the one they are on right now, the ‘make Brexit work’ model. This means tinkering with policy and working to reestablish good faith relations, possibly with a few new agreements of the kind already mentioned on trade, energy and possibly security.

This keeps things contained and allows the party to focus on what it sees as the lower-hanging fruit on economic and social reform that voters want. It also limits getting dragging into justifying itself to a Conservative opposition.

But it also means that there is a conscious closing off of options that might produce more significant effects down the line, economically and politically.

Hence the other, radical option is to use popular disillusionment over how Brexit was ‘done’ to leverage much closer ties with the EU. These ties would markedly improve (or more accurately, undo the damage done by withdrawal) economic access to the European market and be a marker of full-spectrum British reengagement with the world (because the current European hole doesn’t really help).

However, this radical model comes with clear short- and medium-term costs. Quite apart from endless Tory heckles about taking the Leave-voting majority for fools, it would suck up a huge amount of political resource, also raising questions about whether the rest of the manifesto could be pursued if new EU-inspired constraints were coming down the line. Plus, the EU might well not want to even play ball in starting negotiations, let alone reach an agreement of such a kind.

Which is all a long way of saying that as things stand now, I’d argue that Labour isn’t going to risk its current position by going for a markedly different European policy. If you want an historical analogy, then it’s a ‘second term issue’, much like single currency membership was for New Labour in 1997.

And you’ll remember how that turned out.