In April earlier this year, I met up with colleagues from the ‘Re-Assembling Democracy: Ritual as Cultural Resource’ (http://www.tf.uio.no/english/research/projects/redo/) research group at the Comptoir Voltaire, a café on the corner of Boulevard Voltaire and Rue de Montreuil, in Paris. Last Friday, at 21:40, a terrorist blew himself up there. The attack on the café was one act in an unfolding horror of a war that has never been declared, has no fixed territory and no clearly defined protagonists. ISIS/ISIL/Daesh, a billion dollar brand franchise, are the enemy, but their fighters are French, Belgian (and British), their Wahhabi ideology is the state religion of the key Western ally Saudi Arabia and numerous theories abound about support ISIS/ISIL/Daesh (may) have received from Assad (to fight the Free Syrian Army), the USA (to fight Assad) and Turkey (to fight the Kurds). Amidst the confusing welter of claim and counter-claim, right-wing media in the UK have linked the attacks in Paris to the refugee crisis. No thought that the refugees are fleeing precisely the same kind of horror. And, more perniciously, in seeking an immediate cause for the violence, the much deeper causes that lie behind the rise of ISIS/ISIL/Daesh are implicitly put to one side in favour of easier headlines that prompt bad decisions by policy-makers.

PhD in Religious Studies: funding opportunities

If you are interested in doing a PhD in Religious Studies at the OU, then you might consider applying for funding through the CHASE Consortium. The new round for entry in October 2016 is now open.

The CHASE Consortium (which alongside the OU, includes the Courtauld Institute of Art and Goldsmith’s College at the University of London and the Universities of East Anglia, Essex, Kent and Sussex) offers fully funded PhD studentships for UK students. (For EU students the award covers fees only.) Up to 75 studentships (part-time or full-time) are available across the consortium for October 2016 entry. The studentships include excellent opportunities for skills training and networking with other students.

To apply for a CHASE studentship, you will need to go through the standard Open University application process, with submission of the application form no later than 13 January. Early application is strongly encouraged. For more information about the application process, please visit http://www3.open.ac.uk/events/jobs/2015113_49612_o3.pdf . To find out more about CHASE, visit the consortium website at http://www.chase.ac.uk/

If you are interested in making an application, we encourage you to contact potential supervisors in the department as soon as possible – please visit http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/religious-studies/staff.shtml

Islamic state, Dabiq, the Mahdi and the end-times

Dabiq is the name of a small town in northern Syria with no special claim to fame apart from the fact that the Umayyad caliph Sulaiman ibn Abd al-Malik (674-717 CE: reigned 715-717) was buried there in 717. So why has Islamic State (ISIS) called the magazine it publishes Dabiq? The main reason appears to be that according to Muslim eschatological tradition it will be the site of a major battle that will be fought between Muslims and Christian invaders, a battle that will be one of the signs that the end-times have begun[1].

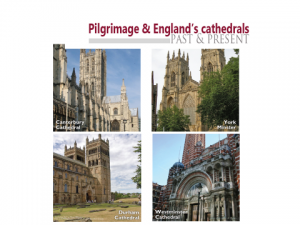

‘Pilgrimage and England’s cathedrals, past and present’

As you know from this blog, the research focus of this Religious Studies department is ‘contemporary religion in historical perspective.’

Fortunately for me, this is at the heart of ‘Pilgrimage and England’s cathedrals, past and present’, the AHRC-funded, three-year research project which commenced in November 2014. Working as a Co-I with Dee Dyas, University of York (PI), Simon Coleman, University of Toronto (Co-I) and post-doctoral researchers Dr John Jenkins and Dr Tiina Sepp (both based at University of York), we have had a busy, fascinating and stimulating year, as you can see from the project website http://www.pilgrimageandcathedrals.ac.uk/

Towards a global history of American evangelicalism

One of my highlights of the summer was taking part in the ‘Towards a global history of American evangelicalism’ workshop at the Roosevelt Study Center, Middelburg, Netherlands. This workshop, funded by the Luce Foundation, followed up from a conference, of the same name, at the University of Southampton in 2014. The workshop was to discuss the planned production of a special issue of Journal of American Studies on the same theme. You can see what a happy and intellectually stimulated group of folks we were in the picture (courtesy of Hans Krabbendam: from left to right, David Swartz , John Maiden, Uta Balbier, Hans Krabbendam, Melani McAlister, John Corrigan, Heather Curtis, Timothy Stoneman, Brandi Hughes, Axel Schäfer and Kendrick Oliver ).

).

The American foreign missionary enterprise expanded from the 1820s, alongside the nation’s economic and imperial growth. During the Cold War period, evangelical missionary work expressed a universalist vision of American power, with Christianity often understood and utilized as a spiritual bulwark against the perceived global threat of Communism. In the later part of the 20th century, the numerical balance of Christianity in the world – and evangelicalism and Pentecostalism – has increasingly shifted to the global south. Scholars have highlighted the emergence of ‘world Christianity’ and the ‘diffusion’ of evangelicalism; and with it indigenous evangelical leaderships and practices, resistance to western paternalism, the reflexivity of missions, and increasingly transnational exchanges and flows of resources. What have been the changes and continuities in American evangelicalism’s engagement with the wider world during this long period?

There were papers here on conferences (1966 Congress on World Evangelism and Lausanne 1974) and organisations (e.g. Prison Fellowship International; Sharing of Ministries Abroad USA); print and radio media; gender and mission; race and civil rights; foreign policy and international aid. The paper I presented concerned ongoing research on an US Episcopalian charismatic mission network, and its activities in Latin America and Africa since the 1980s. I argued that this network displayed a strong emphasis on the mutual sharing of resources and responsiveness to local priorities and leaderships in its work with dioceses abroad; and this reflected both and a growing emphasis in evangelical theology and practice of mission on interdependence and a blurring of lines between ‘sender’ and ‘receiver’. I’ll keep you posted on developments with the special issue as they emerge.

Iconoclasm, Daesh and Modernity

Howls of outrage from Western media greeted recent evidence of organised iconoclasm by Daesh. Footage of statues being destroyed by cadres armed with drills and sledge hammers in what is thought to be a museum in Mosul in Iraq (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-31647484) followed claims that they had also burnt down the city’s library. Since then, evidence has emerged that they have bulldozed the archaeological site at Nimrud (http://www.wsj.com/articles/islamic-state-militants-bulldoze-ancient-nimrud-archaeological-site-1425600798). This latter act was described as a war crime by the UN and has fed a frenzy of media stories about Daesh (‘Isis demolition is war crime against heritage, says UN’ The Times 07-03-2015). In this short post I follow the example of thought experiment cum unsettling juxtaposition (of Immanuel Kant and Sayyid Qutb) by Caroline Rooney in her piece ‘From Religion and Security to Religion and Liberty’ http://www.paccsresearch.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Religion-Security-Global-Uncertainties.pdf). Specifically, I want to juxtapose acts of iconoclasm from sixteenth century Europe and twenty first century Iraq to interrogate how they are narrated and understood.

During the sixteenth century, European cities including Antwerp, Basle, Wittenberg and Zurich were rocked by riots, arson, looting and the removal, theft or destruction of books and statues (among other things) from convents and churches. Inspired if not actually led by men such as John Calvin, Andreas Karlstadt, Martin Luther and Heinrich Zwingli, these upheavals have become integral to a popular historical and sociological narrative whereby Protestant rationalization of (pathologically) elaborate (and corrupt) Catholic ritualism opened up space for the emergence of a new (but gendered) subject able to access the Word (of God) and interpret it without the mediation of the Catholic Church. This event transformed Western Christianity (and indeed ‘religion’) into a private mental state called belief, and envisioned ‘the believer’ applying Reason to read and interpret Scripture. This story (or myth) elided the iconoclastic violence of the Reformation to tell a story about freedom from despotic authority and the emergence of Reason. Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism implicated this subject and the narrative of freedom and Reason in the development of capitalism and the modern political and social order or in short, modernity.

It is important to draw responsible conclusions from thought experiments of this kind. A simple place to begin might be that contemporary understanding of the Antwerp iconoclasm of August 20, 1566 (represented by Hogenberg in an etching titled The Iconoclasm c. 1570, showing the looting and destruction of a church by men carrying clubs under the cover of darkness – note the figure bottom right carrying a candle https://www.google.co.uk/search?q=hogenberg+iconoclasm&espv=2&biw=1517&bih=714&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ei=bGkVVay4L87iapnYgAg&ved=0CAYQ_AUoAQ&dpr=0.9) is dramatically different from the people who actually lived through it. Catholic commentators of the time certainly did not regard it as an event likely to precipitate any kind of Enlightenment. In like fashion, understanding of the Mosul and Nimrud iconoclasms is likely to alter through time. But benign historical relativism is not where I want to end. The iconoclasms at Mosul and Nimrud are difficult to understand but most difficult of all is the recognition that Daesh see themselves as engaged in emancipatory acts guided by the application of Reason. As such, their acts of iconoclasm are unfolding within what is a very familiar mental architecture. Is it possible that by seeing ourselves in Daesh we will understand ourselves and Daesh with greater clarity? And by doing that, will we in turn become much clearer about the people we want to be and the kind of society we want to preserve?

Paul-Francois Tremlett

New video on teaching RE

We’ve been asked to publicise this new video to recuit applicants for RE. Please promote ‘RE: teaching beyond the ordinary’ through your networks.

We’ve been asked to publicise this new video to recuit applicants for RE. Please promote ‘RE: teaching beyond the ordinary’ through your networks.

http://www.teachre.co.uk/beyondtheordinary/

“So much universe, so little time”: honouring Terry Pratchett

Terry Pratchett, creator of the Discworld and co-creator of the Long Earth died at home on Thursday 12th March 2015, aged 66. His award winning books and talks have amused and inspired many. They have also sometimes provoked new thoughts and even awed or humbled us. How do you tell people that you are dying, slowly as parts of you fail? Terry Pratchett, inspired by Richard Dimbleby’s taboo-breaking announcement of his struggle against cancer, told the world. His support for dementia research was more than financial – although he was more than generous financially too. His efforts were of a piece with the kind of thing his Discworld characters would do: naming a demon as a first step in slaying it. Terry was also a vociferous supporter of the right to live and die with dignity. He insisted that being able to chose when to die was a matter of decency and respect for life.

Terry Pratchett, creator of the Discworld and co-creator of the Long Earth died at home on Thursday 12th March 2015, aged 66. His award winning books and talks have amused and inspired many. They have also sometimes provoked new thoughts and even awed or humbled us. How do you tell people that you are dying, slowly as parts of you fail? Terry Pratchett, inspired by Richard Dimbleby’s taboo-breaking announcement of his struggle against cancer, told the world. His support for dementia research was more than financial – although he was more than generous financially too. His efforts were of a piece with the kind of thing his Discworld characters would do: naming a demon as a first step in slaying it. Terry was also a vociferous supporter of the right to live and die with dignity. He insisted that being able to chose when to die was a matter of decency and respect for life.

Skydiving!!!

This month Clifford Dadson, who studied A332 Why is religion controversial? with us this year, is turning 95. Cliff not only completed a BA Open (Hons) this year as the oldest OU graduate, he also took part in a tandem skydive from 13,500ft, which raised nearly £2,000 for the charity Action for Children. Happy birthday, Cliff!

Times Higher awards!

The OU’s Religious Studies department has long been known for its formal dress code. Here are John Wolffe, John Maiden and Gavin Moorhead attending the Times Higher Education awards in London, where the project ‘Building on History: Religion in London’ was shortlisted in the Widening Participation or Outreach Initiative of the Year category.

This public engagement initative enabled the project team work alongside various community stakeholders in order to enhance understanding of the history of religious diversity in London and promote local engagement with religious history. You can learn more about the project at http://www.open.ac.uk/arts/research/religion-in-london/ .

The project team are joined here (top picture) by Graham Harvey (RS Head of Department) and Annika Mombauer (Associate Dean, Research). The University of Sheffield – many congratulations to them – were eventually presented with the trophy by the comedian Jack Dee, but even so it was a great evening!