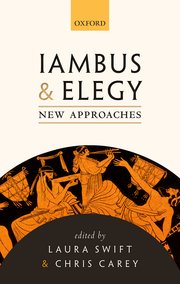

I’m really happy to be joining Classical Studies at the Open University, in my first post since finishing my PhD. I’d like to thank publicly all of my colleagues for already having made me feel so welcome! Having discovered Classics by accident when I was persuaded to sign up for a Classical Civilisation A level instead of one in History, I began my Classics career in earnest as an undergraduate at Royal Holloway, University of London in English Literature and Classical Studies. While there, I began work on the Athenian forensic speeches in a dissertation on legal language and rhetoric in [Demosthenes] 59 Against Neaira; the forensic speeches would come to be my primary research focus. I then moved to the University of Bristol, where I gained a Masters in Classics and Ancient History and continued my interest in forensic rhetoric with a dissertation on invective in the courts. Finally, I ended up at University College London to study for my PhD under the supervision of Professor Chris Carey. This project, entitled ‘Athenian Homicide Law in Context’, explored the distinctive nature of homicide in Athenian law and culture, and the ways in which the legal system set homicide apart from other crimes. My primary focus was exploring how this distinctiveness played out in rhetoric, by examining several prominent features of forensic speeches on homicide: Athenian ideology, religious pollution, relevance, and the twin issues of motivation and intent. The project illustrated that although the Athenians would regularly speak about homicide in a way that implied it was always subject to especially solemn and rigorous treatment, in practice speeches in trials for homicide or where homicide was a secondary issue were just as commonly exploited for personal and political gain as any other. A secondary goal of the project was to explore the courtroom context of delivery and the effects this may have had on rhetoric; I noted several significant differences between homicide rhetoric delivered in the homicide courts and that delivered in the popular courts. I am currently in the process of turning my thesis into a book, provisionally titled Homicide in the Attic Orators: Rhetoric, Ideology, and Context.

The next research project that I’m looking to undertake grows out of the secondary conclusions from my thesis. I’m interested in how space and place played various roles in Athenian oratory – of all genres, not just forensic. In this project, I’ll be following two major strands of enquiry. Firstly, I’ll look at how the physical space of delivery could affect the rhetoric used in a speech, by way of both visual impact and ideology. In the case of the homicide courts, the visual and ideological markers of religious solemnity – the location of all of the homicide courts at religious sites, the proximity of shrines to the Areopagus, the performance of distinctive sacrifices and the swearing of particularly weighty oaths – must have made the religious danger of homicide causing pollution particularly clear to those present at the trial, and therefore may have decreased the need for or effectiveness of pollution rhetoric. This might partly explain the apparent dearth of references to pollution in the forensic speeches for homicide. I’ll examine how this pattern extends across the courts, the assembly, and locations for public funerals, by looking at the physical features of the delivery spaces, as well as the psychological associations that they would have for those present. My second strand of enquiry looks at how spaces and places are constructed, invoked, and used rhetorically in the speeches, particularly in addressing issues of identity and ideology. The very existence of places – in my framework, locations with a particular meaning to a particular individual or group – implies identity, both for the place and for the people for whom it is meaningful. Spaces – locations defined more physically – often have effects on individuals’ behaviours and identities. Both spaces and places can invoke strong ideological associations, an effect that was no different in Athens. Thus, these themes could be deployed in rhetoric to particular effect in front of Athenian audiences. I am currently preparing a chapter on an initial case study for this project, entitled ‘Space, Place, and Identity in Antiphon 5’.

Besides my primary research interests, I’m particularly keen on 20th and 21st century receptions of Greek drama. While at UCL, I helped to organise a series of events called Conversations with Iphigenia, which presented discussions between the playwrights of the Gate Theatre Notting Hill’s Iphigenia Quartet, other theatre practitioners, and academics from Classics, Theatre Studies, and Translation Studies. A transcript of the roundtable discussions from these events will appear in the OU’s Practitioners’ Voices in Classical Reception Studies journal in 2018. I also work regularly with the London-based By Jove Theatre Company, where I am their research and education co-ordinator and blog editor. By Jove focus on new writing, particularly women’s writing, that presents old stories for a new audience, and has staged new versions of Greek tragedies, Shakespeare plays, and Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice over the last 5 years. For more on the company, or to read the blog, see www.byjovetheatre.org. I’m also really interested in applications of feminist theory and translation studies to Classics.

When I’m not doing research, teaching is my passion. Though I enjoy teaching all aspects of Classics – particularly themes on Classical Athenian history, society, and culture, as well as Greek law – I’m an especially keen teacher of Ancient Greek. My favourite classes are students of Greek who are coming to the language as undergraduates or later, as I myself never had an opportunity to study ancient languages at school, and only started study as an undergraduate. Such courses tend to be fast-paced and high intensity, and thus require a lot of dedication and persistence – from the teacher as well as the student! Nevertheless, some of my most rewarding teaching experiences have been in Greek classes, where students have finally grasped a difficult grammatical concept after a long struggle. I think there’s a lot of enjoyment to be had in learning Greek, not only because of its extensive and poetic vocabulary and far more precise grammar than in English, but also because translating a complicated passage often feels like trying to break a code – with the same sense of achievement (and access to hidden information!) when you’re done.

I’m really looking forward to my next two years at the Open University, and I hope to meet many new faces along the way! If you’d like to find out more about me, follow me through the next couple of years, or just say hi, you can find me on Twitter @chrissieplastow or on my personal website and blog at christineplastow.com.