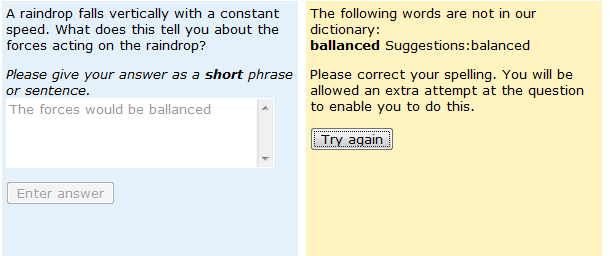

I get asked a lot about how the answer-matching copes with poorly spelt responses to our short-answer free-text responses, and this is certainly something that used to worry me. Fortunately all the evidence is that our answer matching has coped remarkably well with poor spelling – and this is true both for the IAT software that we used to use as well as the PMatch software that we use now. We’ve dealt with poor spelling in a number of different ways – for a long time we relied on fixes within the answer-matching software itself, but we now also use a pre-marking spell-checker, which warns students if they use a word that has not been recognised and suggests alternatives, as shown in the screen-shot shown below.

For obvious reasons, our analysis of spelling mistakes in student responses has used responses gathered before the introduction of the pre-marking spell-checker.

So how many of these responses contained spelling mistakes? This varied considerably, depending on the question and the mode of use (summative, formative, diagnostic), but an analysis of seven different questions and between 1500 and 20,000 responses per question showed there to be between 4.3% and 14.8% of responses that included at least one spelling mistake. At the lower end of the range were questions that could be answered using simple words in relatively common usage e.g. ‘The oil has lower density’ , ‘The forces are balanced’, ‘There is no verb’ whereas those at the upper end of the range frequently involved particular words associated with a large number of spelling mistakes, both words with a specialist technical meaning e.g. ‘fragmental’ and those that are in more-or-less everyday use in the English language e.g. ‘crystal’ and ‘align’. You would not believe the number of different ways people spell ‘crystallisation’, even allowing for the alternative ‘z’ and ‘s’ spelling. Where the same question had been used formatively and summatively, there are fewer spelling mistakes in summative use than formative-only use. Where the same question had been used formatively and diagnostically, there are fewer spelling mistakes in formative use within a module than in diagnostic use (when people used the quiz to self- assess their preparedness for study).

Is there variation in accuracy of spelling between first, second and third attempts? We wanted to investigate whether people corrected spelling errors in their responses when told that their response was incorrect (perhaps linked to thinking that they were being marked as ‘wrong’ because of incorrect spelling). Remember that at this stage no feedback was being given on spelling but in most cases spelling errors were not getting in the way of accurate answer matching. Therefore we decided to test the null hypothesis that the spelling error rate was the same at first, second and third attempt.

We were forced to reject our null hypothesis – but not for the reason we’d expected. For virtually all uses of all questions, the proportion of responses containing a spelling error increased from first to second to third attempt. We looked at some responses to investigate this more thoroughly and noticed that whilst students tend to correct typos (e.g. missing spaces between words) when they have been told that their answer is incorrect, they do not correct words that are in themselves incorrectly spelt (e.g. seperate instead of separate). Then, when students add to their answer at second or third attempt, they introduce more spelling errors. In particular, in adding to responses, students frequently end up with two words running together. It is also worth noting that second and third attempt responses are from the weaker students – the strongest students will have got the question right at the first attempt.

Is good spelling associated with correct answers? In general, correctly spelt responses are more likely to be correct in content than responses containing at least one spelling mistake. For some questions the differences were highly significant.