Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Past Issues

- Issue 5 (2014)

- Benjamin Jasnow and John Woodman

Benjamin Jasnow and John Woodman

.jpg)

John Woodman is an English painter who has exhibited across the United Kingdom and internationally. His most recent solo show took place at the Milton Gallery in London in 2013. Ben Jasnow is a Classicist and poet based at the University of Virginia. In this interview conducted via Skype in August of 2013, Woodman and Jasnow talk about their ongoing project to illustrate and translate the Idylls of Theocritus, an ancient Greek poet from Sicily (3rd century BC), credited with the invention of pastoral poetry. Each verse translation is paired with several of Woodman’s contemporary, interpretive illustrations. In April of 2013 they exhibited a selection of their work at the Bridge PAI in Charlottesville, VA, and hope to publish an edition of their illustrated translation in the near future.

Benjamin Jasnow's translations of Idylls 1 and 6 are available as a PDF file and also appear at the end of this interview.

JW. What drew you to Theocritus, and how did you come up with the idea for a collaborative approach?

BJ. Theocritus was so different from anything I’d ever encountered. I didn’t know what to make of him, especially his bucolic poems. The bucolic, or pastoral, world has this special type of physical beauty that’s charged with divinity and danger. The shepherds always sing in a shady spot, beside a spring or a brook, enclosed by lush vegetation. But lurking in the background is the threat of angering Pan, or being snatched away by the Nymphs. I was attracted to this from the beginning.

And then there’s the incredible difficulty of the poems—I can’t figure them out so I can’t let them go. The Idylls are so complex in their tone—grotesque and sublime, funny and dead serious. The ambiguity of the Idylls, the way that Theocritus is able to approach a topic from different angles, that’s one of the real pleasures of his poetry.

This complexity is one reason I thought illustration would suit Theocritus well. There are so many different sides to his poetry that no translation is going to be able to pick up every angle. But with you as a visual translator, making pictures and approaching the poems from your own perspective, then someone who reads our translation might get a fuller experience of the Idylls. Having pictures and words together broadens the interpretive context. Theocritus can be really difficult, since he’s full of unfamiliar names, places and situations. I hope that your images will catch the attention of people who wouldn’t otherwise have been interested in Theocritus, or in Ancient Greek poetry. And then they’ll get trapped like I did.

How about you? What was your first reaction to Theocritus?

JW. I didn’t know anything about Theocritus when you suggested this idea to me. As you say, not knowing the context in which Theocritus is writing or the references that he is making can be alienating. We began with Idyll 7, and I remember reading it with my sketchbook and being amazed by the description of the yearning for a boy felt by Simichidas’ male friend. It is shocking that it could be described without any kind of judgment or moral implication as would happen now. It suggested some very potent images.

It’s amazing how much I have sympathised with the characters Theocritus describes. When reading the Idylls, the context slips away and the situations in which these characters find themselves take precedence. These situations feel very natural and are just the kind of things that we deal with every day. For example, Polyphemus in Idyll 6 is a really moving character. His deluded speech perfectly describes the perverse mixture of loneliness and pride that one can see so often in single men. Similarly the jilted young girl in Idyll 2 is remarkable. She feels the abandonment so keenly and gets caught up in it with just the right level of intensity for someone of that age. There is a wonderful naivety about her which most people will recognise from their own experience. That Theocritus was able to inhabit the mind of the girl so convincingly is amazing.

BJ. So what have been your biggest artistic influences for this project?

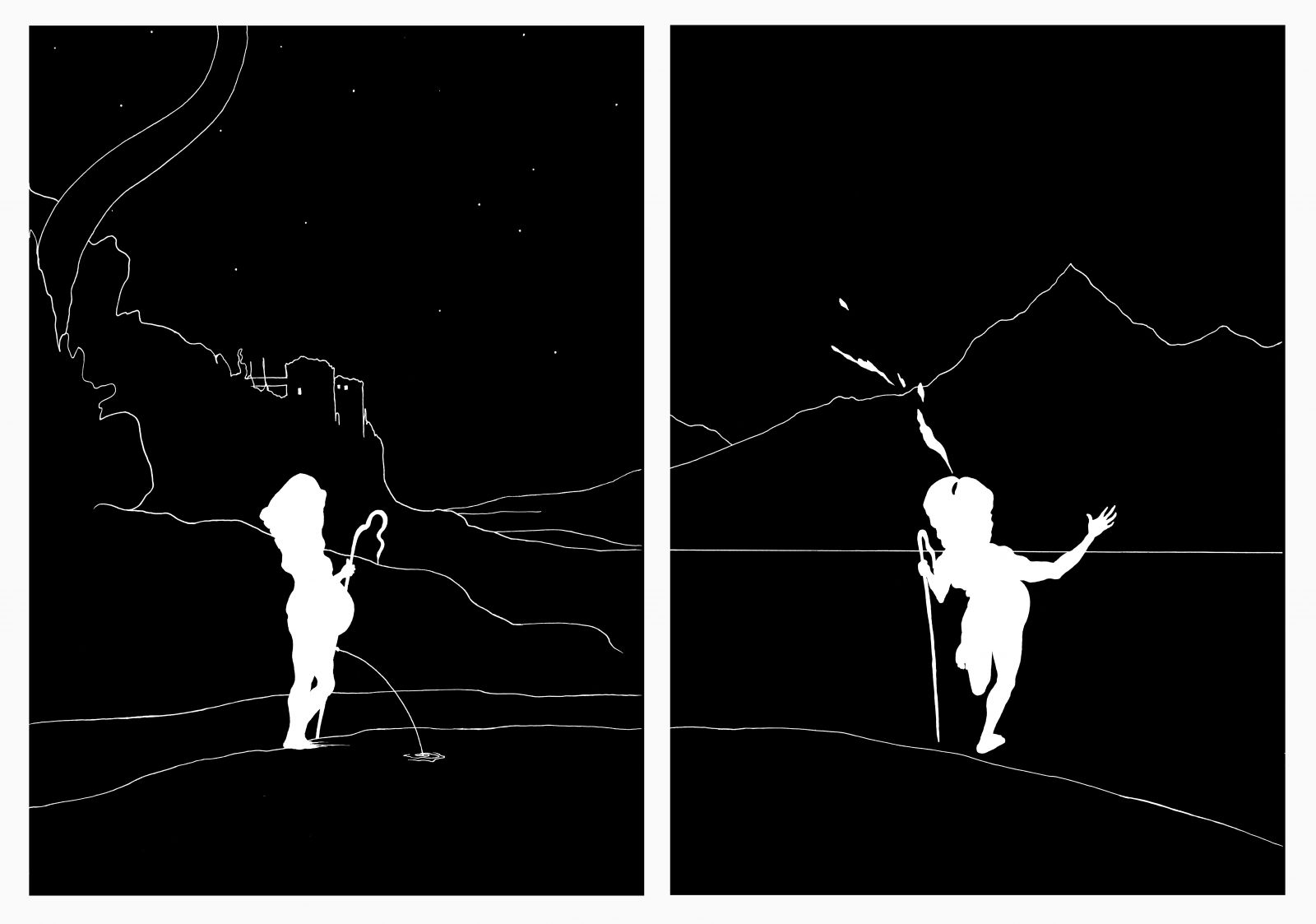

JW. There are lots of artists that influence all of my work, but for this project I particularly had in mind the silhouette work of Kara Walker, and The Eraser and Amok album artwork by Stanley Donwood. I love their approach to monochrome work and thought it was just the right method for the Idylls. People often mention Aubrey Beardsley to me when they see the pictures but I actually do not know his work very well.

The way I use colour in my painting is very hard to replicate in printed form. As such black and white images really do make a lot of sense. I also wanted something that would force me to work quickly. When I paint I can be a bit pedantic and this would require lots of images for each Idyll: it had to be a quick method! This has been one of the nicest elements of this project. Making so many pictures has allowed me to dip into lots of different ways of making images and this is feeding back into the painting.

BJ. So there are practical advantages to using black and white. What types of artistic concerns went into that decision?

JW. Practical issues are always important in such decision-making. That said, it is not the only concern. There is a kind of jarring sensation that happens when you look at a silhouetted image: it takes time for the image to clarify and it is rather akin to my experience of reading Theocritus. When it clicks, it’s hard to shake. Originally I wanted to only use silhouettes but as more images are made it becomes clear just how many things one can do with black and white. It is really exciting.

How do you approach translating the poems? Who are your influences?

BJ. My approach changes poem by poem, and that’s by design. The first thing I do is sit down with an Idyll and reread the Greek carefully, letting the poem do its work on me. I try to assemble a reaction to the work, more of a feeling than anything I can articulate at first, although I’m sure my scholarly work also ends up influencing this type of aesthetic response. Then I begin to consider issues of poetic form, like rhythm and verse length, that might help me convey my impressions. My chief concern throughout a translation is to try to come up with verse that is in keeping with this impression I’ve formed, and will hopefully come close to replicating that emotional reaction in my readers.

So, literal linguistic accuracy is not always of first importance. I’m hoping instead for a different kind of accuracy, something more like aesthetic accuracy. I want to replicate the types of sounds and rhythms that Theocritus uses, his tone and linguistic register. In many cases a totally ‘literal’ translation would really be far less accurate, because it wouldn’t satisfy any of the aesthetic concerns of the poem. Idyll 1 is a good example, since it uses a refrain. I needed to convey the rhythmic, religious force of the refrain, which is calling on the Muses to inspire—to conjure up—an entire mode of poetry. This one repeated line bears a huge amount of poetic weight. And that’s how it feels in the Greek. But a literal translation into English just couldn’t convey all this. It would have gone something like this: ‘Begin, dear Muses, begin the bucolic song.’ Instead, I wanted something that sounded a bit like a magic spell and had the rhythmic force of an incantation, and also felt somewhat like a folk song. To achieve that, I had to make some changes to the original. I made the refrain two lines instead of one, and changed the language. ‘Begin, my Muses, my Muses bring, / Begin the song the herders sing.’

An important influence in this regard has been British and American folk poetry and folk song. I like to sing and play a little Appalachian music, which has its roots in Britain. Since the bucolic poems (at least ostensibly) claim a heritage in folk poetry, I try to think of those rhythms when I’m translating, where it’s appropriate. Of course a major influence has been Theocritus himself, and Homer, since they both used Dactylic Hexameter. And then there are English language poets who, like Theocritus and Homer, have a rhythmic power combined with grace: Whitman, Hopkins, Thomas, Pound.

JW. What makes Idyll 1 such an important and meaningful poem?

BJ. Idyll 1 is positioned as the first poem in the collection, but it is also the ‘first poem’ in a more metaphorical sense. Theocritus was supposedly the inventor of Greek bucolic poetry, the first author to take this kind of folk song and raise it to a high literary level. Idyll 1 initiates this new mode of poetry, almost literally: it calls on the Muses to ‘begin bucolic song’. The poem dramatises the creation of this new type of poetry, but also the creation of art and culture in general. Two shepherds meet on a beautiful, deserted mountain side, and they agree to exchange works of art, a beautiful goblet for a beautiful song. The topic of the song is the death of Daphnis, the legendary first singer of bucolic poetry. Within that song, Daphnis himself is portrayed as singing, lamenting his own death. So the poem is very much about the creation of art—art from chance encounter, art from beauty, from other art, from suffering.

How did you come up with the images for Idyll 1?

JW. We both took a long time to work on Idyll 1. When I first read it, some vivid descriptions in the poem suggested images such as the old fisherman or the setting sun. These were very easy and quick to make. I then got stuck trying to depict Daphnis. I tried to do what had worked so well with the fisherman and sun images and be quite literal in my depiction: even having confused conversations with my Dad who was translating specific words for me trying to help me work out what was going on. I only found out how to depict Daphnis Dying after you and I spoke in Charlottesville about him. You tried to explain who Daphnis was and did an impression of what you imagined his death looked like: wading into the water all the time melting into droplets. This had a massive impact and made the picture very clear in my mind.

Do you feel a pressure trying to do justice to Theocritus’ poems?

BJ. Oh God, yes. I have stayed up at night, worrying about the translations. It’s a fine line to walk, to make the translation poetically satisfying, yet also convey the sense of the original. I don’t want to do Theocritus a disservice.

How about you?

JW. I don’t really feel a pressure in that way. It is different for me working in another medium. I feel an obligation to our efforts and want to make images for each Idyll that feel like a complete set. It is important too that both of us are in pulling in the same direction. I normally start working from Verity’s translation and later as your translation arrives in my inbox change to that one. It is amazing how different they tend to be. It always makes me rethink my understanding of the writing and thus my approach to the drawing. Over time we both bounce off each other and eventually end up with something which tends to be quite surprising. Idyll 1 is a great example of the clarity your writing brings to my work. The end of that poem is quite convoluted and hard to interpret. It is wonderful but finding the right images for it was very tough. It took a long time and the final image is almost an abstract response.

BJ. That reminds me. I hadn’t yet received any images from you when I completed my first draft of Idyll 7. But then I got your pictures, which were so visceral, and I realised I had not done my job well enough. I scrapped my draft and began again.

JW. When there is a famous section of a poem, or a particularly important portion, do you approach it differently?

BJ. I wouldn’t say so. I take a careful approach to every passage, and try to strike the right tone. That’s my goal in every case.

I do feel a pressure to live up to Theocritus, like I said before. And I suppose part of that pressure, to me, is capturing the complexity of the characters he portrays. There has been some tendency, I think, to belittle or dismiss certain figures from the Idylls, and I do try to stick up for them. The end of Idyll 7 comes to mind. People have tended to think of that poem’s narrator as somewhat ridiculous. But at the end of the poem he has this incredible communion with the natural world, at a festival to Demeter in her sacred grove. It was important to me that I convey the beauty and gravity of that moment. Earlier you mentioned the Cyclops, from Idyll 6. I really wanted to capture the humor of his speech, much of which lies in what you might call his lack of self-awareness, while also communicating the pathos of his situation.

Many of your images are very funny, and a lot of this humour is sexual. Can you explain the role of sexuality in your illustrations?

JW. The sex in Idyll 1 and in Idyll 7 is described pretty clearly in the text. The description of the shepherd being jealous of the ram mounting the sheep is an amazing section and the imagery it conjures is at once very funny and very sad. The sexual element in the image of Daphnis Dying is there in part to explain why it is he is dying. He says it himself:

I am lost at the hands of Love,

Drawn already into Hades.

I also really liked the other implications it brings when included in this picture. It complicates the feelings he might be having. It is important that it be relatively hidden. The viewer tends to read the title and take in the rest of the picture, then this element can come as something of a shock and cast doubt over their earlier impressions.

BJ. What about the illustrations for Idyll 6?

JW. Idyll 6 was an extremely difficult one to get right. The poem is quite short but touches on lots of different themes and tones. The first image I had in mind was Polyphemus blowing on a pipe while someone danced along a trunk of a fallen tree. I could see the image really clearly and felt that it would do justice to the serene elements described towards the start of the poem. However the drawing would not work no matter how many different approaches I tried. Whenever this happens it means that there is some fundamental mistake in what you are trying to do. In this case I was sticking too closely to the text. Instead the best way to tackle this Idyll was to use the fact that I sympathised so much with the Cyclops. Cyclopes have been very badly depicted in art. There are terrible examples of human beings with a single eye in the middle of their foreheads, and yet two hollows where human eyes would be as well along with random floating eyebrows. The only good examples I can think of are those by Redon and Turner – and Turner did it by turning it into something of an abstraction. If you imagine drawing a Cyclops there is a very clear danger that the head will look phallic, which could undermine the story you are trying to tell. However the proud manner that Polyphemus has and the shortsighted way he interprets his situation suggested that you could use the phallic imagery when drawing his head quite directly: you can turn it into something else entirely. Once this decision was made I imagined a huge number of situations which I could draw, most of which were quite humorous. That said I find these drawings of Polyphemus are the most moving ones for me. Polyphemus is a tragic and very recognisable figure, so the important thing for me was to find a way of showing these things. Although these pictures could be interpreted as poking fun at him (as could Theocritus’ poem) I rather hope that the empathy I feel for the character will come across most of all. None of the Cyclops images are described in the poem. But in some cases sticking very literally to depictions of the text does not actually give you an accurate response to the poetry.

How do you bridge the gap between translation and poetry?

BJ. I think that’s true of the poetry, too, that being too dogmatic about the literal meaning of the text may lead to a less accurate translation overall. But still, I almost envy your position as a visual artist. I am bound to the text—I’m not entirely free in my response. The translations are very much filtered through my own aesthetic vision, but, in the end, I am doing my best to convey what is on the page. There’s always an element of failure in that effort, since what’s on the page is so complex. But often your images develop the themes of an Idyll that wouldn’t be in the foreground otherwise. That’s why our project is best viewed as a whole, and why an illustrated translation is so appropriate to this poet. Viewing both of our individual responses to the Idylls at the same time makes for a richer interpretive experience, hopefully giving access to Theocritus’ genius, but also making something new.

John Woodman (info@johnwoodman.com) and Ben Jasnow (bbj9t@virginia.edu).

IDYLL 1: THE SONG OF THYRSIS (translation by Benjamin Jasnow)

THYRSIS

Sweet song of whispers, goatherd, there, by the springs,

The pine tree sings, and you too sound sweet

On your pan-pipes. You’d be first after Pan, second place.

And if he’d get the he-goat with horns, you’d get the she.

And if he’d get the she-goat as his win, you’d

Get the kid. And the flesh of a kid is fine till you milk it.

GOATHERD

Sweeter still is your song, shepherd, than the splashing

Stream as it slips off the stones from high up.

If the Muses will lead off an ewe as their gift,

You’ll take a lamb from the pen for your glory. But if they

Are pleased to take the lamb, you’ll lead the ewe and go after.

THYRSIS

Would you please, in the name of the Nymphs, be pleased to sit

On the slope of the ridge, where the tamarisk is, goatherd,

And play us your pipe? In the meantime I’ll pasture your goats.

GOATHERD

It’s not right, shepherd, at noon we’ve no right

To play the pipe. Pan keeps us frightened. For it’s just then

He’s tired from the hunt and comes in to sleep, but

Sharp tempered. And an angry rheum hangs always at his nostril.

But since you, Thyrsis, always sing the Sorrows of Daphnis,

And the songs of the herders are your deep devotion,

Let’s sit beneath the elm and by Priapus,

Facing the Nymphs of the springs, just where the shepherd’s seat

Sits amongst the oaks. And if you should sing as once

You sang in your match against Libyan Chromis,

I’ll give you a goat with twins to milk three times,

(She may have two kids, but she’ll fill two pails besides),

And this deep wood cup, washed over with sweet wax,

Two-handled, new-cut, the scent of the blade still on it.

Up at the lip of the cup winds ivy,

Ivy twined with helichrysum, and all throughout

The tendril twists in the glory of its golden fruit.

And there a woman, like a wonder of the gods, is crafted,

Adorned with a robe and a fillet. Two men crowd round,

Lovely themselves with their long hair; each with the other,

Each with the other they quarrel with words. But she

Pays them no mind. Now laughing she glances at one of the men,

Now again her will flits in another direction. But they

Labor in vain, a long time, with swollen eyes, for love.

Alongside these a fisherman is crafted,

And a rough rock, where he’s standing, looking lively.

The old fisher’s hauling in his huge net for a cast;

He looks just like a man working hard.

You’ll say he’s fishing with all the strength of his limbs;

All the muscles of his neck are straining,

Even if his hair is grey. He’s got a young strength.

Just a bit further on from the old, sea-beaten man

Is a beautiful vineyard, weighed down with bunches of dark grapes,

And a small boy sits on the wall of dry rocks,

Keeping watch. But a couple of foxes get right past.

The one creeps through the rows, plotting mischief

For the fresh fruit; the other’s using all her craft

To get at the boy’s satchel and says she won’t let up

Until she gets to breakfast on his biscuits.

But the boy, meanwhile, plaits a lovely cricket cage,

Weaving asphodel with rushes. He has no care

For his satchel, nor do the vines concern him,

Not nearly so much as he rejoices in his weaving.

And curling acanthus spreads over the chalice in every direction,

A goatherd’s marvel, a wonder to bewilder your heart.

I gave a goat to a Calydnian ferryman for it,

And I paid him a big, white, milky cheese besides.

It hasn’t yet touched my lip, but still it remains

Unused. I would gladly offer you this pleasure,

If only you, my friend, would sing me that lovely hymn.

I won’t sneer. Come then, man, for you can’t

Keep a song down with Hades, who utterly forgets.

THE SONG OF THYRSIS

Begin, my Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

I am Thyrsis, my voice is fair,

Fair-voiced is Thyrsis of Aetna.

Where Nymphs were you then, when Daphnis longed,

Nymphs, when with love he was drowning?

Did you get by Peneius, its lovely glades,

Did you get by the glades of the Pindus?

For you did not stay by our mighty flood,

You abandoned the river Anapus;

You abandoned Aetna and its climbing crags,

And the hallowed streams of the Acis.

Begin, my Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

As he died they were howling, the jackals and the wolves,

The lion did lament him from the coppice.

Many cows round his feet, and many were the bulls,

Many calves and heifers who were crying.

Begin, my Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

First came Hermes down from the mountain,

And 'Daphnis,' did Hermes say,

'Who wears you down, O good my son,

For whom is your love so great?'

Begin, my Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

There came the neatherds, came shepherds and the goatherds,

All asked what the sorrow might be.

Priapus came, and said 'Daphnis, wretch,

Oh why do you melt away?

For there's a lass who waits at every fountain

She wanders through the glades for thee.'

Begin, my Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

'You love like flint, you're set as stone,

No more do you a neatherd seem.

But like a goatherd watches how the she-goats bleat,

And watches as they're mounted by the hes,

And he melts with longing, and he drowns his eyes

That a billy he's not born to be,'

Begin, my Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

'So you, when you see the maidens how they laugh

Your eyes melt just to dance with them.'

To these the neatherd made no response,

Naught but continued all the same,

And brought to an end his bitter love

And brought to an end his fate.

Begin again, Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

And sweet Cypris came, laughing all the time,

She was laughing in her secret heart,

But in anger she spoke, heaving with rage,

'You boasted you could wrangle Love.

But Daphnis, now, tell me who is tripped up,

And who bested by grievous Love?'

Begin again, Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

'Cypris of grief' did Daphnis now answer,

'Cypris who nurses resentment,

Cypris detested by all mankind,

Do you dream that our sun has set?

To Love will Daphnis be a hateful spite,

Always, and even in Hades.'

Begin again, Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

'And who hasn't heard of Cypris and the neatherd?

Get then to Ida and Anchises.

There the bees are humming, lovely by their hives,

There are the galingale and oaks.'

Begin again, Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

'And Adonis is there, in his perfect hour,

And there puts his sheep out to pasture,

And there takes aim at every hare

And tracks every beast of the mountain.'

Begin again, Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

'Or go face to face again with Diomedes,

Stand close to him and say,

"Now I have vanquished the neatherd Daphnis,

Come, then, and fight with me!"'

Begin again, Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

'Farewell O wolves, O jackals, farewell,

O bears who are lurking in the mountains,

I Daphnis no longer am neatherd in your woods

No longer in your glades or in your coppice.

Arethusa farewell, and the beautiful waters

Of the rivers pouring from the Thybris.'

Begin again, Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

'Daphnis am I, who in this place

Puts out his cows to pasture;

Daphnis am I, who in this place

Waters his bulls and his heifers.'

Begin again, Muses, my Muses bring,

Begin the song the herders sing.

'O Pan, Pan, if on lofty Lycaeus,

If you haunt enormous Maenalus,

Now come to the island of Sicily,

Leave the Helice highland,

And leave the steep barrow of Lycon's son,

Grave that's a wonder to the gods.'

Bring an end, Muses, my Muses bring,

Bring an end to the song the herders sing.

'Take my pipe, my Lord, well-bound about its lip,

That smells like honey from the wax,

For I am lost at the hands of Love,

Drawn already into Hades.'

Bring an end, Muses, my Muses bring,

Bring an end to the song the herders sing.

'Now the brambles, may you blossom with violets,

And blossom with violets the acanthus,

The juniper grow lovely with locks of narcissus,

Each thing become another.

Let the pine bear pears, since Daphnis dies,

Let the hart now rend the hound.

Let the wide-eyed owls sing down from the mountains

And drown out the nightingales.'

Bring an end, Muses, my Muses bring,

Bring an end to the song the herders sing.

He said so much and stopped. And Cypris

Wished to raise him back up,

But the flax of the Fates had spun too far

And Daphnis went into the flood.

The eddies washed over the friend of the Muses,

Whom the Nymphs had never detested.

Bring an end, Muses, my Muses bring,

Bring an end to the song the herders sing.

Now, give me the goat and the pail, so I

Can milk her and pour to the Muses. Farewell,

Ye Muses, a thousand times farewell. For you

I’ll ever sing another hour, a sweeter song.

GOATHERD

Full of honey be your lovely mouth, my Thyrsis,

And full of honey-comb too. May you eat

A sweet fig from Agilia, since you sing

Better than any cicada. Here’s your chalice. See

How beautifully it smells, my friend. You’d think

The Hours had filled it at their spring. Cissaetha,

Come ‘ere. Go on and milk her. But you, miss goat,

Had better not strut, or that billy’ll get right up.

IDYLL 6: DAMOETAS AND DAPHNIS SING THE CYCLOPS (translation by Benjamin Jasnow)

Damoetas and Daphnis the neatherd, once,

Aratus, gathered their herds together

In a single spot. The one of these boys

Had just sprouted golden down, the other

Already had half a beard. These two

Sat near a certain spring, the both of them,

On a summer noon, and this is what they sang.

Daphnis went first, since he first made the challenge.

THE SONG OF DAPHNIS

Galatea’s slinging apples at your sheep,

Polyphemus, and taunting

Never will you learn to love a girl,

Just stick to goat-herding.

And you, poor Cyclops, never look her way,

Just sitting and piping

That sweet song. And now she’s pelting

The bitch who looks after your flocks.

It barks and looks into the ocean

And the lovely waters show

The dog’s reflection, racing up and down

The softly breaking shore.

Careful, Polyphemus, or the bitch’ll sic

Galatea as she’s coming from the water

And tear up the lovely skin

Of her ankles. But she’ll

Just flirt from there, Galatea;

Just like the lightest threads

Of thistledown, when summer’s fair and parching,

She flies from the one who loves

And chases the one who doesn’t,

Desperate to make a move.

For in love, Polyphemus, very often,

When fair seems fine, it isn’t.

Then Damoetas piped a prelude, and this is what he sang.

THE SONG OF DAMOETAS, SINGING AS POLYPHEMUS

I swear to Pan, I saw her throwing

Apples at my sheep;

It didn’t escape me, nor my one sweet eye,

Which I pray will see to the end.

And may Telemus, that seer who makes

Such baleful pronouncements,

Bring bale on his own house; he can

Keep it for his children.

Now I’m the one who’s teasing Galatea;

I never look her way, I say

I have a woman already. And when she

Hears that, my god,

She gets so jealous that she

Melts, she goes crazy,

Peeping up from the sea, looking

At my cave and at my sheep.

It was me who sicced my dog to howl,

Since, when I was in love,

It wined with its snout on its haunches.

And, maybe, when Galatea sees

Me doing these things so often,

She’ll send me a message.

If not, my door is locked, until she

Agrees to make

Her beautiful bed with me, here,

On my island.

Because my face isn’t nearly

As ugly as they say.

Just yesterday, when it was calm,

I looked into the sea,

And there, in that reflection, my beard

Was beautiful, and my

One eye was beautiful, at least

If I’m the judge,

And the gleam of these teeth was brighter

Than Parian marble.

To block the evil eye, I spat

On my breast three times;

It was the old witch Cotyttaris

Who taught me that.

When he’d said this much, Damoetas

Gave a kiss to Daphnis, and the one

Gave his syrinx to the other, and the other

Gave his lovely flute. Now Damoetas

Played the flute, and Daphnis the neatherd

Piped on the syrinx. And straight away

The heifers began to dance

In the tender grass. Victory belonged

To neither man, but both went unbeaten.

Find out more...

John Woodman's artist website contains a series of videos filmed at the Ancient Songs, Modern Muses exhibition in Charlottesville, as well as more images from the Theocritus series.