Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Past Issues

- Issue 5 (2014)

- Gillian Bevan

Gillian Bevan

Gillian Bevan is an actor who has played a wide variety of roles in West End and regional theatre. Among these roles, she was Dorothy in the Royal Shakespeare Company revival of The Wizard of Oz, Mrs Wilkinson, the dance teacher, in the West End production of Billy Elliot, and Mrs Lovett in the West Yorkshire Playhouse production of Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Gillian has regularly played roles in other Sondheim productions, including Follies, Merrily We Roll Along and Road Show, and she sang at the 80th birthday tribute concert of Company for Stephen Sondheim (Donmar Warehouse). Gillian spent three years with Alan Ayckbourn’s theatre-in-the-round in Scarborough, and her Shakespearian roles include Polonius (Polonia) in the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre production of Hamlet (Autumn, 2014) with Maxine Peake in the title role. Gillian’s many television credits have included Teachers (Channel 4) in which she played Clare Hunter, the Headmistress, and Holby City (BBC1) in which she gave an acclaimed performance as Gina Hope, a sufferer from Motor Neurone Disease, who ends her own life in an assisted suicide clinic. During the early part of 2014, Gillian completed filming London Road, directed by Rufus Norris, the new Artistic Director of the National Theatre. In the summer of 2014 Gillian played the role of Hera, the Queen of the Gods, in The Last Days of Troy by the poet and playwright Simon Armitage. The play, a re-working of The Iliad, had its world premiere at the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre and then transferred to Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, London.

Chrissy Combes spoke to Gillian at the Globe Theatre on 27 June, the day before the final performance of the play.

All production photographs are reproduced with the kind permission of Jonathan Keenan.

CC. I am talking today at Shakespeare’s Globe in London to the acclaimed actor, Gillian Bevan. This summer, 2014, Gillian has been playing the role of Hera in The Last Days of Troy, a play by the poet Simon Armitage. The play had its world premiere in May at the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester, and then transferred here to Shakespeare’s Globe in June for a short season. There will be one more evening performance tonight (27 June) and then a final matinee tomorrow, after which the run will end. Gillie, I know you will be off to Manchester again soon, to start rehearsals for the role of Polonius (or Polonia) in Sarah Franckom’s production of Hamlet at the Royal Exchange. So thank you very much indeed for making the time now to talk to me about The Last Days of Troy.

GB. Hello Chrissy, It’s good to meet you and to talk to you.

CC. I wonder if we can begin by discussing Simon Armitage and the genesis of this play? Simon Armitage is, of course, a greatly celebrated poet, and rightly so. He received the CBE for Services to Poetry in 2010 and he has published ten volumes of award-winning poetry in the UK and the USA, in addition to versions of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and The Death of King Arthur. He is also a broadcaster, a playwright, a novelist, and a writer for television and radio. His harrowing Black Roses - The Killing of Sophie Lancaster, initially written as a drama documentary for BBC Radio 4, transferred as a play to the Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester, to very great acclaim. All in all, his output is staggering. But, perhaps, an aspect of his work which will be of greatest interest to PVCRS readers is his fascination with Greek mythology and classical themes. For instance, his play Mister Heracles is based on Euripides’ Heracles. Above all, Simon Armitage seems to be drawn again and again to Homer. He adapted The Odyssey for BBC Radio in 2008, and, two years later, produced Gods and Monsters, a programme for BBC2 about Odysseus’ journey home from Troy. In the programme, the poet was filmed sailing from Troy to Ithica, re-tracing the full journey of Odysseus. And The Last Days of Troy is largely based on The Iliad. So, do you think that writing The Last Days of Troy was something Simon Armitage felt compelled to do in order to complete his work on Homer?

GB. Yes. Absolutely. Simon talked about it a lot. He adapted The Odyssey several years ago and after that he certainly felt that he had unfinished business with regard to Homer. But he said he needed the right opportunity to do this new play, to get a commission, to have something to fire him up to do it, as opposed to just doing it on spec. As you know, Simon lives in West Yorkshire, and one day he had a chance meeting in Hebden Bridge Cafe, he was having a cup of coffee there, and Sarah Franckom, Artistic Director at the Manchester Royal Exchange, also happened to be there. They were chatting, and she asked him what he would write if he had the choice of doing absolutely anything he would like to do. He said straight away that he would write a play about Troy, the last days of Troy. And that’s how it all began, there in the cafe.

CC. And the finished piece has the absolutely glorious role of Hera, Queen of the Gods, for you.

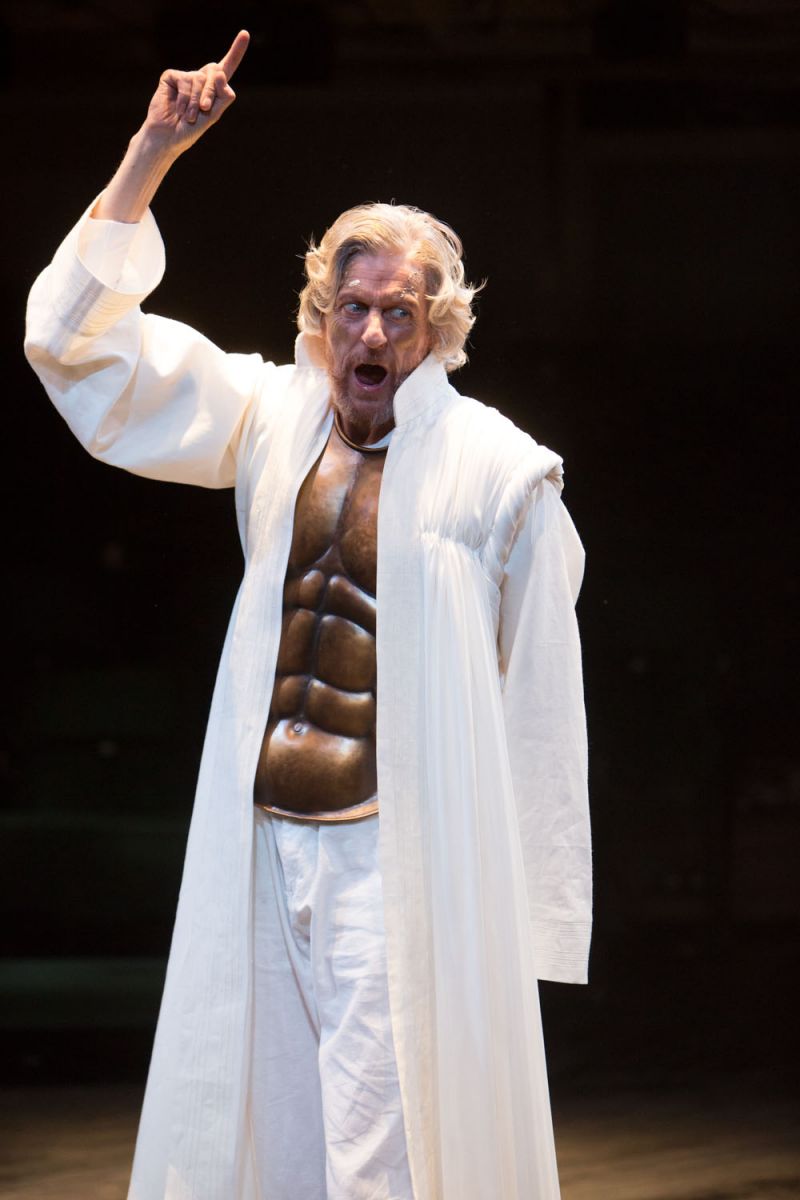

Gillian Bevan as Hera in ‘The Last Days of Troy’

GB. Oh yes, I have loved playing this character, she is wonderful. In fact, they are all wonderful characters!

CC. As in The Iliad itself, Simon Armitage makes Hera and the gods into important players in the action, doesn’t he? And, it is fascinating to see that he translates many major and iconic episodes from The Iliad to the stage, bringing out the dramatic qualities of the epic poem for contemporary audiences. To name just two examples, the touching scene from Book 24 of the The Iliad, where Priam pleads with Achilles for the return of Hector’s body, and the beautiful episode from Book 6, Hector’s farewell to Andromache and Astynax, clearly moved audiences when performed onstage.

Hector’s farewell to Andromache. Simon Harrison (Hector) and Clare Calbraith (Andromache)

GB. Yes, there are so many very touching scenes in the play. Garry Cooper (Priam) and Claire Calbraith (Andromache/Thetis) played many of them, brilliantly.

CC. And the director and designer have used the theatre spaces very imaginatively to bring these scenes alive. For instance, the famous scene from Book 3 where Helen identifies to King Priam each of the Greek warriors, from the vantage point of the battlements of Troy, above the Scaean Gates, worked extremely well when played up on the first gallery at the Royal Exchange.

DB. And also, after we transferred here to the Globe, the scene was played from a gallery position, with Priam and Helen talking across the groundlings from opposite sides of the auditorium.

Helen reviews the champions. Garry Cooper (Priam) and Lily Cole (Helen of Troy) at the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre

CC. But the play is not simply a re-working of The Iliad itself, is it? Homer’s epic poem focuses on just a few weeks from the Trojan War but Simon Armitage has added to the material, showing the ending of the war and the fate of the principal characters. He has taken the story to a conclusion. Could you please tell us about his sources for The Last Days of Troy?

GB. Well, I think The Iliad contributes to about two thirds of Simon’s play. Homer leaves the story at the funerals of Hector and Patroclus. Simon continues and completes the story. His source for details about the fall of Troy is Virgil, the Roman poet, who was obviously writing many years after Homer. As you know, Virgil’s poem The Aeneid tells the story of Aeneas , who escapes from Troy and goes on to be the founding father of Rome. In Book 2 of The Aeneid Aeneas recalls how Troy fell, there is narrative about Sinon and the wooden horse, and so on. So Simon used all that detail (Brendan O’Hea played Sinon as well as Patroclus in the play). And Simon also referred to a couple of passages from The Odyssey where the wooden horse is described. And then he invented other scenes, threads to do with the death of Paris, for instance, and he created a final scene on Troy’s beach. And, in fact, in the published version of the play, you will find these scenes, including the death of Achilles – a superb scene.

CC. So Simon Armitage has combined old and new material in the play?

GB. Yes, a great deal of material. In fact, when we had our first preview (the World Premiere!) we didn’t come down until 11.15 pm – extremely late. Both Simon and Nick Bagnall, the director, needed to see the piece in its entirety at least once before cuts were made. We had a meeting the following morning to shorten the play. Everyone understood the necessity of this and what had to be done, and many of us suggested cuts that could be made from our own parts (even if they were our favourite bits). We effectively reduced the running time so that the play came down by 10.30 p.m. It was a big ask for author, director and company, and I was proud of how everybody dealt with what could have been an agonising process. Unfortunately, the death of Achilles got lost in this process. But it is certainly there in the published text, and was played superbly all through rehearsals – and for that one opening night – by Jake Fairbrother.

CC. Might I ask you about the text? The language seems very muscular and vivid. I would imagine it’s a good text to speak?

GB. It’s fantastic, because it is dealing with epic themes, of course, but it is very visceral as well and also very contemporary, and often very funny. And it works well for a young audience, particularly at the Globe, where you can pay £5 and stand for three hours, which is hard, particularly if you don’t know the context of the play. Simon is very keen, and Nick is very keen on absolutely making sure that the story is central and that the whole thing moves along at a fair pace. Simon has written a wonderful new piece of epic poetry but he knew that Nick needed to theatricalise it so that it could stand on its own as a play. I think, between them, they have achieved that really well.

CC. It must have been a mammoth task for Simon Armitage to reduce the sources to something that was manageable and accessible onstage. He was spanning two great Greek epic poems and one Latin epic poem, as well as adding material of his own, in order to complete the story of Troy in its final days. Yet the structure is tight and the narrative is clear. And there seems to be a real balance in the text between current, quite spare prose, and beautiful, very rich verse passages, doesn’t there?

GB. Well, Simon is one of our greatest living poets. Some of his images take your breath away

CC He brings out the scale and the grandeur of the events. Was he a presence at rehearsals?

GB. Yes, he was. He came for a few days early on and we could all ask him our questions. It was such a fantastic opportunity to have the author there for a while (something you don’t have if you are doing a classical text such as Greek tragedy or Shakespeare). He said something wonderful one day. Everyone in the company had done lots of research before rehearsals started and we were forever going up to him saying ‘Should I do this? Should I do that? Hera is the goddess of this and also the goddess of that. What bits of mythology should I use?’ And he said ‘Look, I’ve done the research so you don’t have to. Just play the scenes.’ And that was quite liberating. He told us to trust him, trust the text. To bring what we wanted to what was there in the text. It was a very generous thing to say to the actors and a great note to be given.

CC. Nick Bagnall. the director, must have himself had a huge task on hand. The Last Days of Troy was being played in repertoire at the Royal Exchange Theatre with Britannia Rules the Waves by Gareth Farr, winner of the Bruntwood Playwrighting competition. Both plays are about men going to war – a fitting theme, of course, during 2014 and the commemoration of World War 1 – and both plays were directed by Nick Bagnall, who then, later, had to transfer The Last Days of Troy to the Globe. What was Nick Bagnall’s approach to rehearsals for The Last Days of Troy?

GB. It helped that Nick had worked very closely with Simon for about two years with regard to the play. He was in on the genesis of the play, discussing how to get it off the page and into the theatre. And he is very conversant with the Globe space, having directed the three Henry VI plays here. In fact, I think it was probably his connection to the Globe that meant we transferred here. And Nick has been an actor so he understands the difficulties that an actor can have with epic language.

CC. Had you worked with him before?

GB. Yes, and most of the cast had worked with him before. He’s absolutely fantastic. He’s like an energetic terrier! He’s got so much vitality and is so inspiring and so appreciative of anything that you bring to the table. He’s so very encouraging and will let you try things out. It feels a very safe rehearsal room. And what was really gratifying is that the cast, everyone, loved this play, loved this piece so much that we wanted to be around all the time, not just for our own rehearsals but to watch all the other rehearsals. For instance those of us playing the gods wanted to watch the rehearsals that the Greeks were in and those the Trojans were in. It soon developed as a kind of trust among us all. The main thing that Nick wanted was to make sure that the story was absolutely clear, that we could all drive on with the story. And he trusted us all enough so that we could all question, ask questions in order to clarify the story. We would all say, I would say things like ‘I’m not sure why Odysseus is doing this, why is Achilles doing that?’And if it wasn’t clear, we would all sort it in a hugely collaborative way. It was a wonderful, very easy rehearsal period in terms of everybody being able to take ownership of the play. And I think, possibly, this was really useful because the play tells such a huge story and the combined experience of that cast was considerable. Obviously, Nick was the leader, he had the final say. But that kind of shared rehearsal doesn’t happen that often.

CC. It occurs to me that the designer, Ashley Martin-Davis, had quite a challenge. The Royal Exchange is in-the-round and an interior space, while the Globe is an Elizabethan platform stage in the open. They are very different spaces, aren’t they?

GB. Oh yes. Ashley Martin-Davis worked very closely with both Nick and Simon to create a fairly minimal, quite spare set that would accommodate the confines of the Royal Exchange but also enable us to bring the play to the Globe. People outside thought the transfer would be relatively easy. They thought because we, the actors, knew the lines it would all be the same once we got to the Globe! But it’s not the same at all. Once we had transferred, the staging was different, the timing of every entrance was different. And, of course, here at the Globe, you are not allowed to have any lighting effects or recorded sound, so all that was very different. You could enhance, say, a battle scene at the Exchange through lighting in a way you can’t at the Globe. And all music and percussion was played live at the Globe.

Lighting effect at the Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester

CC. Could we talk about the Trojan horse a little? It is never mentioned in The Iliad though it is referred to in The Odyssey and of course it is described in detail in Book 2 of The Aeneid. Simon Armitage wanted the wooden horse to appear in the play, but perhaps this was the greatest challenge of all for the designer, especially with two spaces? Could you explain the two differing interpretations of the horse for us?

GB. Well, at the Exchange we had this marvellously symbolic representation. A huge wooden drum descended from the ceiling. The drum encompassed the young boy playing Astyanax bringing on a little tiny toy wooden horse. It was a wonderful image. But, of course, at the Globe you can’t fly down a massive wooden drum. So, in this space, it was decided that the entire auditorium should, in a sense, become the Trojan horse. The actors simply stare upwards. It is almost as if the Trojan horse is coming out of the sky. Then, eventually, the actors playing the Greek soldiers emerge from under the stage, via the built in trapdoor. It works extremely well, the trapdoor suddenly opens and the Greeks emerge from it. And audiences go with it, you know. They know that in a film, such as Troy, you can have a realistic representation of the wooden horse. But they also understand that The Last Days of Troy is a piece of theatre, that imaginations have to be used.

CC. Did Ashley Martin-Davis design the costumes as well?

GB. Yes, Ashley did a wonderful job of making things clear and keeping things simple. The Trojans are in a sort of beautiful mulberry purple costume and the Greeks are in dark black and brown. That really helps the storytelling, clarifying who is in each camp. For the gods, he wanted to bring in echoes of Greek statues so the gods are dressed beautifully in white and gold.

On Mount Olympus. Richard Bremmer (Zeus) with Gillian Bevan (Hera) and Francesca Zoutewelle (Athene, with helmet)

CC. Let’s talk about those gods now. In his Introduction to the published text of The Last Days of Troy Simon Armitage describes how, for dramatic purposes, he had to reduce Homer’s pantheon of gods to just four: Zeus, Hera, Athene and Thetis, Achilles’ mother. In the play, he makes Zeus and Hera both gods of the ancient past and contemporary characters. They frame the action, almost like a Greek chorus. Zeus, in particular, plays a big narrating role. In fact, it is Zeus, as a contemporary character, who opens the play, posing as a living statue and holding aloft a cardboard imitation thunderbolt. Could you talk about Zeus and Hera as both the ancient and modern characters

Richard Bremmer (Zeus) in the opening scene of ‘The Last Days of Troy’

GB. Yes, I think that Simon’s treatment of Zeus and Hera is an inspired device which works extremely well in the play. They have scenes both as the original gods, living on Mount Olympus, and as contemporary down and outs, living in present day Troy. Simon actually got the idea when he went to Hisarlik in Turkey which is, obviously, the site believed to be that of ancient Troy, and is a famous archaeological and tourist venue. On one visit to Hisarlik, he saw a man standing on a suitcase, pretending to be Zeus. So he absolutely stole that idea, and it is a marvellous device, although rather sad. In one line of the play Zeus says: ‘I ruled over the cosmos once. Now look at me, a glorified beggar, seller of knick-knacks and souvenirs.’ Zeus and Hera have been forgotten because people no longer believe in them. I think that Simon feels nowadays we have lost our gods. Our gods are reduced even though they are meant to be immortal. The gods of banking, the gods of religion, the gods of the church. We’ve had the Leveson inquiry – the gods of the press can no longer be trusted. Society has lost its way; we don’t have any belief. There is constant war. And the genius of Simon’s writing is that he always manages to make it really personal so it has resonance to us in our daily lives. It is really interesting to see Zeus and Hera brought down to such meagre circumstances. For instance, in one later scene, Hera is reduced to peeling potatoes and scrabbling around to get a meal together. It is almost as if Zeus and Hera, king and queen of the gods, have become Syrian refugees. Symbolically, that helps an audience to engage with the concept of the breakdown in society, in the cosmos, and with the effects of warfare within the epic nature of the play.

CC. So, it is very much the idea of the death of god? Rather, the death of gods?

GB. In a sense, yes. Although near the end of the play, Zeus laments the fact that he is immortal. And Hera comments wittily that he has an eternity to get used to the idea! But we talked about the nature of belief a good deal in rehearsal, the role of religion, and who would have believed in what in Homer’s time. I suppose throughout history there have always been people who go along with the public face of religion. But it is very much less the case today and for today’s audiences.

CC. The appearance of a spray-painted Zeus with a collection tin is a terrific theatrical idea as well, isn’t it? It makes such a clever opening to the play. In the production, Zeus (Richard Bremmer) addresses the audience, asks the Goddess of Memory to draw from his throat the story of Achilles and his wounded pride, then takes little action figures of Achilles, Agamemnon and Priam out of his suitcase to illustrate the siege of Troy, as he begins to describe it. And Richard Bremmer draws the audience into the story immediately. He holds them from that moment, doesn’t he?

GB. He is a marvellous actor, and he has a great deal of work to do in the play. He has the lion’s share of the big speeches. He does it all terribly well.

CC. Later in the play, he lists the famous ‘catalogue of ships’. Simon Armitage condenses the passage from The Iliad, but the speech is still very lengthy and extremely detailed. It must be a devil to remember and to deliver?

GB. Yes, but Richard does it brilliantly. He talks to the audience, stages it, makes it thrilling to watch, makes them see the ships. The speech brings home to the audience how this extraordinary Greek fleet has been built up, how men from this disparate group of islands and men from the mainland have come together as a nation for the first time, under a common cause.

CC. Could you describe how you and Richard Bremmer portray the ancient gods in their home on Olympus? I am wondering whether you make any distinction between playing the contemporary characters and the gods of the ancient past? For instance, do you want to represent any super-human qualities when you are on Olympus ? Or suggest divine immortality?

GB. Both in Homer and in Simon’s play, there is a very domestic quality to the gods. We discussed the nature of godhead but we discovered quite early on the domestic nature in Simon’s language. And he (again, like Homer) essentially uses the gods as a comic device. The subject matter about war is so grim, you want some humour to alleviate that. When something terrible is at issue, lots of playwrights, such as Shakespeare, will flip a play on its head a bit. This is what Simon has done. And all the gods’ scenes, whether modern day or on Olympus, are beautiful to play, especially at the Globe. The groundlings absolutely appreciate the humour and the irony of the scenes. The gods are really fun characters to play, so recognisable. Hera, of course, is written as a nagging spouse and Zeus talks about getting grief from his wife. For instance, he is especially uneasy in the scene where Thetis comes in to charm Zeus, to persuade him to side with the Trojans.

Thetis visits Zeus. Clare Calbraith (Thetis) and Richard Bremmer (Zeus); Francesca Zoutewelle (Athene) in background

CC. And Hera, who has been quietly watching Zeus and Thetis, has a great first line: ‘I saw that!’

Hera (Gillian Bevan) reacts to the meeting between Zeus and Thetis

GB. Yes, it is a wonderful first line. Zeus is completely caught out. There is always a great burst of laughter from the audience. Nick is always very keen to emphasise any of the lines that can be at all comic. So, at the Globe, while Zeus and Thetis are onstage, I watch them from different positions in the yard. I am in among the groundlings, watching the scene with them, sharing the situation.

CC. It is fascinating to see how closely and how cleverly Simon Armitage has translated the events from Book One of The Iliad to the stage.

GB. Yes. And this scene is very important, both in the poem and the play. Thetis persuades Zeus to favour the Trojans at the request of Achilles who, of course, feels himself hugely insulted and is enraged by Agamemnon’s taking of Briseis. The course of the war changes when Zeus nods to Thetis.

The rage of Achilles. Jake Fairbrother (Achilles) and, his back to camera, David Birrell (Agamemnon)

CC. Hera is immensely jealous of Thetis, isn’t she?

GB. Yes, she is, but she has a lot of cause. She feels that Thetis and Zeus have been scheming behind her back, conniving, hatching plots. And Zeus, of course, is basically a philanderer. Hera certainly has a right to be jealous. She is portrayed as the nagging wife and he as the henpecked husband. But my sympathies lie very much with her, she can’t trust him.

CC. And Hera’s sympathies lie very much with the Greeks, don’t they?

GB. Oh yes, ever since the rejection of Hera and Athene in the Judgement of Paris, both goddesses have been hostile to the Trojan camp. Both Zeus’ wife and his daughter firmly support the Greeks.

CC. In Homer and in Virgil the gods are continually taking sides, playing with the heroes, controlling the action. This same sense of divine intervention, of the gods being key players and having favourites, is evident in the play. Paul Vallely (Independent) in his review of The Last Days of Troy describes the gods in the play as ‘petulant squabbling partisans’. Yet, although there is a great clash of wills between Zeus and Hera, she is afraid of his anger, isn’t she? He can silence her?

Zeus silences Hera. Richard Bremmer as Zeus, the king of the gods.

GB. Oh yes. He is the king of the gods. And, as in Homer, Simon indicates a dangerous back story between Zeus and Hera, the fact that Zeus has much more power in their relationship and has the ultimate power on Olympus. So, although they both have their favourites, and although she riles him and tells him off in public, she knows he is capable of great violence. When Zeus finally shouts her down because he objects to her interference over his decision to back the Trojans, she has to capitulate. But it’s different in the modern scenes. This is where Simon’s writing is so brilliant. In Olympus, Zeus is quite scary. Even though Hera is queen of the gods, he is all powerful. But, curiously, in the modern day scenes it is almost as if he is a man who has been a chief executive and has had to retire and doesn’t quite know what to do with himself. And in these scenes, Hera comes into her own. She looks after him, she cares for him. She is the one who is peeling the potatoes but she is also organising him, looking out for him, telling him to pick up his suitcase as there’s a tour bus coming and they need to earn money in order to eat. I think it is deliberate in Simon’s writing, Hera is in charge in these modern scenes. And Zeus is very sentimental about their relationship.

CC. Yes. There’s a beautifully written scene between Hera and Zeus near the end of the play which is quite tender, isn’t it? It is in the middle of all the scenes of fighting, and the two gods sit side by side and reminisce about their very first meeting when Zeus appeared to Hera in the guise of a cuckoo.

ZEUS: A poor little cuckoo with a broken wing. The illusion was quite astonishing.

HERA: You flapped about at my feet. So to keep you warm I lifted you into my arms.

ZEUS: To your breast, Hera. Lifted me to your breast. And the rest, as they say, is history.

HERA: In fact these days they say it’s mythology.’

(Lines from ‘The Last Days of Troy’ by Simon Armitage).

GB. Richard and I love playing this scene. And Nick hit upon the idea of not removing any of the bodies from the stage. There is still Paris’s body onstage. The scene takes place with Paris’s body there. And Zeus is still obsessed, even thousands and thousands of years later, with what happened at Troy, and with how responsible he was for all the carnage. So it is interesting to play that lovely scene just in a lull in the fighting, with blood all over the stage. That scene, with its gentle banter and reflective mood, is beautifully written and beautifully placed in the piece.

CC. Let’s not forget that it is beautifully played as well, by two astonishingly accomplished actors! But, talking of the fighting, the play is often very grim to watch. The death of Hector is horrifying...

The death of Hector. Jake Fairbrother (Achilles) and Simon Harrison (Hector)

GB. Yes, the battle scenes are terrific, all choreographed by Kevin McCurdy. You really believe in the brutality of what is happening in front of you. The killing of Hector by Achilles is especially dreadful to watch, and Achilles’ mutilation of Hector’s body, the cutting of his tendons, is chilling.

CC. It also comes through strongly in the play that women are victims in war as well as men. At one point Hera, goddess of marriage, voices concern for the suffering of the women of Greece.

GB. Yes. The gods are not angelic gods. They are always bickering, highly competitive, very capricious. But they are quite human in many respects. And they are sensitive to the fact that that bad things happen to good people. And, in war, those people are often the children and, of course, the women on either side, for instance, Briseis who is a war prize, Andromache who becomes a war widow, even Helen. After all, Helen sings ‘The Song of the Lonely Wives’ in the play.

The Song of the Lonely Wives. Lily Cole as Helen of Troy

CC. Again, Lily Cole singing that song was a stand-out scene. In writing the scene, Simon Armitage was clearly referring to Book 4 of The Odyssey, Menelaus’ description of Helen standing underneath the Trojan horse and calling out to the Greeks in the voices of their wives, in order to lure them out. Nick Bagnall describes in the programme how he asked Simon Armitage to write a lyric for a Helen of Troy song in this scene. He comments that when he saw the finished words to the song, it was an unforgettable moment in his life because the words were so heart-breaking they made him gasp.

GB. The song is incredibly beautiful. Lily sings it in Greek, but the lyric captures the agony of the wives who are always watching, always waiting for their soldier husbands to sail off to new wars in new countries: ‘Leaving us shell, Leaving us sand.’

CC. So, do you think that Simon Armitage is engaging with war from the female perspective?

GB. Yes, he definitely has compassion for women and their grief during war. And in this year, which marks the centenary of the 1914-1918 war, the theme has great relevance. Wives suffer terribly. So do mothers when their sons go off to fight. I mean, look at Thetis, both in Homer and in the play. She is a sea nymph, a goddess, but although she knows Achilles is fated to die once he has killed Hector, she cannot prevent her son’s death, indeed, she gets him new arms. In the scene after Patroclus’ death, where Thetis comforts Achilles, you see her agony too; the audience has sympathy for her.

Thetis cradles Achilles. Clare Calbraith (Thetis) and Jake Fairbrother (Achilles)

CC. What about Helen? Do you think that that the audiences are intended to have sympathy for her?

GB. Helen is a challenging character to write and to portray. She is extraordinarily beautiful, a living legend. And she is one of those characters who is projected upon, especially by men. But Simon’s interpretation of Helen is so clever. He says that in The Iliad she is a shadowy figure, little more than a walk on part, so he wanted to make her more pivotal, more central. She still works at her embroidery, as she does in Homer, in the play she is embroidering a tapestry (not a robe) depicting the events of the war as they happen, and you are never really sure which side she is presenting herself on in the tapestry. Is she Trojan? Is she Greek? Was she abducted? Was she seduced? Even at the end of the play, you are still not really sure whether she went to Troy willingly. Paris doesn’t even know. And I love what Simon has done with Paris as a character. He is beautiful but so flawed, a bit of a dilettante. But when Troy has been destroyed he is absolutely desperate to know whether Helen will die with him or return to Menelaus and go back to her old life. Tom Stuart, who played Paris, conveyed that need to know so well, and the audience identified with him at that moment.

CC. Lily Cole plays Helen as very remote, very cool, quite secretive, doesn’t she?

GB. Helen is an enigma and I think Lily does an extraordinary job with her. She brings out how isolated Helen is. Andromache is hard on Helen. She says that when Helen walks in a room, the men smell sex, that Helen has been sleeping with men since she was the age of ten. Helen’s retort is that she was actually raped on a riverbank at the age of ten and there was no sleep. The point is that she didn’t have much choice. Women didn’t. Andromache dislikes Helen but Helen is wise, she understands human psychology she reads people and she understands where Andromache’s hardness comes from. She has become hard herself and that fact has saved her life. To a great degree, Helen is a survivor. She was a queen in Sparta. She is a princess in Troy. And highly respected in Troy, people pay court to her. She survives. The men are definitely bamboozled by her but she is a very isolated figure. At the end of Simon’s play, Menelaus doesn’t come to claim her.

CC. Yes. In Euripides’ The Trojan Women Menelaus is a character. But there is no Menelaus in The Last Days of Troy, is there?

GB. No. Simon had to reduce the cast of The Iliad to about twelve people. He omitted Menelaus for that reason, but as the play developed, he found Menelaus’ absence to be a very useful dramatic device. For instance, in the final scene, on the beach, Menelaus isn’t eager to see Helen, even though the war has supposedly been fought and won for her. Agamemnon tells her that Menelaus is down on his ship, stowing the vessel with gold and diamonds, the plunder from Troy. And his absence makes the audience question the real motives behind the war. Menelaus isn’t rushing up to Helen, saying ‘Hi Darling, how are you? Odysseus actually says to Helen at the end: ‘Do you really think Greece risked its life to haul home an unfaithful wife?’

CC. The character of Odysseus is able to see matters clearly throughout the play, isn’t he?

GB. Oh yes. And it is a wonderful performance by Colin Tierney. He shows that Odysseus is a brave soldier, very strong and courageous, but also a highly intelligent man, a great strategist who is always thinking, always assessing a situation. Always weighing things up.

Colin Tierney as Odysseus

The male characters in the The Iliad, live by the heroic ideology. They are willing to look death in the face, to fight for glory and immortality. Do you think Simon Armitage is portraying the male characters in the play as extraordinary heroes?

GB. Yes. But he makes them flawed as well, as they are in Homer. Simon’s characters are very layered and that makes them so interesting. They are a bit like Shakespearian characters. They have foibles. Look at Agamemnon. He is a great king, a great warrior, but there is something of the little boy about him as well. He’s preoccupied with all the trappings of kingship. He is bossy with Odysseus, quick to order him around, but has to take guidance from him often. And his quarrel with Achilles, the squabble, that is quite reminiscent of many contemporary politicians. And conflict so often starts for petty individual reasons, then it escalates into the slaughter of thousands of men.

CC. The wrath of Achilles drives the action in The Iliad, reverberates through it. Does this come over in the play?

GB. It does. It is an extraordinary feud between Agamemnon and Achilles and it has dreadful consequences. Everyone suffers because of it, the women suffer, particularly Briseus. I would say that Achilles is a bit more rational compared with Agamemnon. But Jake (Fairbrother) gives a passionate, very physical performance and conveys the character’s wounded pride, his sense of being greatly dishonoured by Agamemnon. And the scene with Priam is wonderful. Achilles has avenged Patroclus’ death by killing Hector but his behaviour with Hector’s body is appalling. In the play you see Jake (Achilles) dragging Hector’s mangled body into his tent. But then the scene with Priam as a supplicant redeems Achilles, it is his saving grace, it restores him to humanity. He respects Priam’s courage, and has Hector’s body washed and returned to him for proper burial. He stops being obsessed with himself and his own love and grief for Patroclus and begins to understand the war from Priam’s viewpoint and sees the terrible effect of Hector’s death on his grieving father.

CC. I’d like to ask you one final question, Gillie. Homer’s epic poem, composed over 3,000 years ago, was itself about war in a previous, remote, archaic age. In your opinion, why does this story still need to be told to contemporary audiences?

GB. Well, firstly, because it is such an exciting, monumental story about the last days of a great, beautiful civilisation, and has such vibrant characters. As Simon says in his programme notes, The Iliad is the fountainhead of Western literature. And we need to have plays like The Last Days of Troy, particularly for young people who might well go on to read Homer and Virgil for the first time after seeing the production. They are spellbound by the play. They gravitate towards the stage, wanting to know what the story is. We have had loads of school parties in and they are really entranced by the story. I think it is especially important that it is being staged now, at the commemoration of the centenary of World War 1. Then, of course, the story has such an extraordinary afterlife. It is still so relevant. The epic poems and the Greek myths and classical drama speak directly to our psyche. The events in them echo through time. I saw a production of The Crucible at the Old Vic last night. Arthur Miller said, when writing the play, that the job of an artist is to remind people of what they’ve chosen to forget. And I think that powerful thought applies to Simon’s play. When we were rehearsing it, the pages of the newspapers were full of the situation in Ukraine, of stories about Syrian refugees, about people leaving Africa in boats. We think that we are civilised today, of course we do, and technology has moved in to our world, but terrible wars are still happening. Zeus says in the play:

‘A blood-coloured river

runs down to the sea

between west and east’

That is sadly, still so true. Simon sees Troy as a blueprint for a conflict that still rages today. He believes that the Hellespont, the channel that runs from the Bosphorus to the Dardanelles, continues to symbolise a political, cultural and religious fault line between east and west. For example, the idea of Turkey being admitted into the European Union causes major controversy. And you can see Troy in the knee jerk reactions of western countries to the east, you can see Troy in the western greed for oil, you can see Troy in the lack of any real understanding of Islam. History repeats itself. And Simon’s play reminds us of that blood-coloured river, something we would rather forget. I feel privileged to have been associated with this fabulous play and I shall miss it very much indeed.

CC. Gillie, thank you for talking to us today about The Last Days of Troy.

GB. Ah, it’s been a pleasure!