Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Past Issues

- Issue 7 (2016)

- Sarah Walton

Sarah Walton

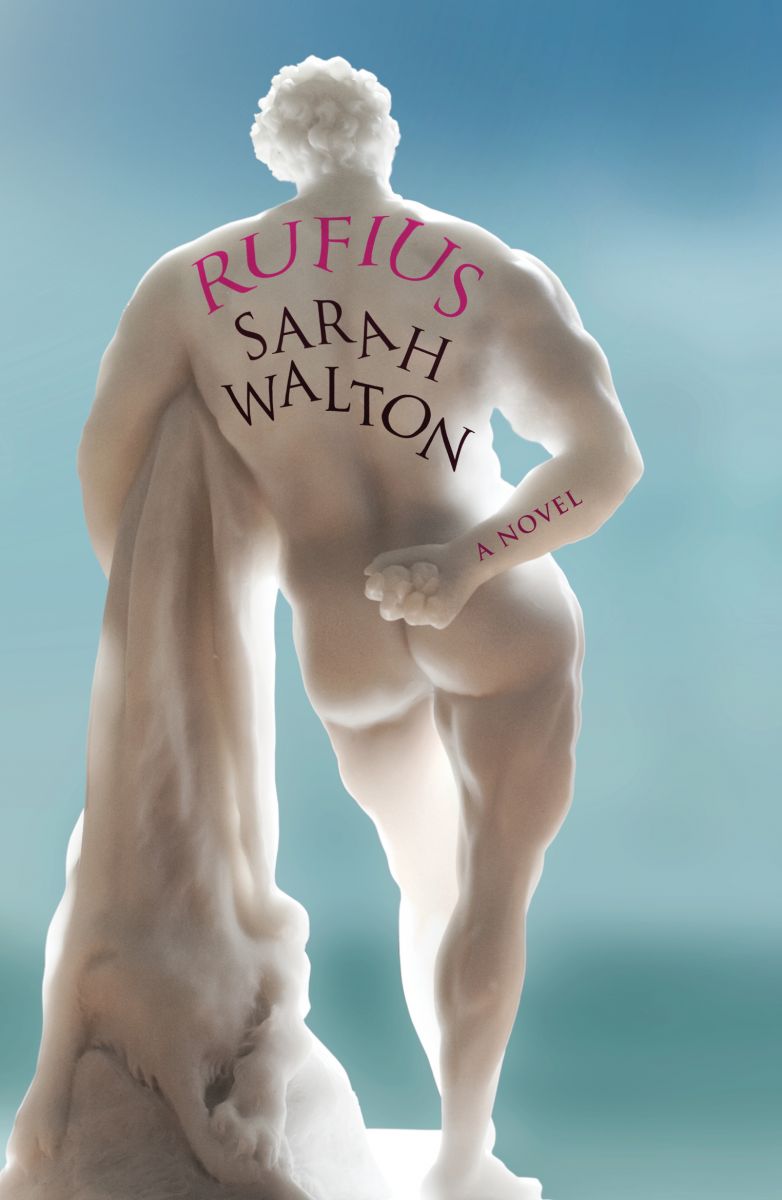

Sarah Walton is a novelist, whose debut novel, RUFIUS (Barbican Press, 2016) is set in fourth-century AD Alexandria. She has a PhD from the University of Hull’s Philip Larkin Centre, where she taught Creative Writing. Her academic research looked at the representation of ancient Roman sexuality and gender in modern fiction and the relationship between history, fiction, film and TV. The Hostess Detective (novel in progress) was long-listed for the MSLexia women’s novel prize. She also has a career in digital innovation.

In this piece for Practitioners’ Voices in Classical Reception Studies, Sarah reflects on the process of researching and writing RUFIUS.

A PDF of this essay is available for download

RUFIUS is an illicit love story set in fourth-century Alexandria during the rise of orthodox Christianity. The novel’s back cover blurb reads:

In 4th Century Alexandria, a poor orphan learns to scribe. Meanwhile Rufius, a rich Roman, tends the books in his care and yearns for the youth on the streets. It’s a time of rampant bishops, mad heretics, and a city so ruled by passion it is set to consume itself along with the world’s greatest library. As the poor boy and the rich Roman unite, hell almost literally breaks loose.

Inspiration for Rufius

The idea, or rather a seed of an idea, was ignited by days spent poring over a Gnostic Christian manuscript, commonly referred to as the Pistis Sophia, in the British Library in 2004 – which resulted in a voice and the images of the characters whose handwriting scribed the Coptic (Egyptian written with Greek letters) [1]. Whilst procrastinating, I had made a random search of the British Library catalogue when I should have been researching another novel, The Hostess Detective. The search results came up with a manuscript called the Askew Codex MS 5114. This ignited my curiosity. I contacted the curator of the manuscript, Dr Nersessian and requested access to the book. He asked me why. As I knew nothing about the book, I said I was doing research on ‘Gnostic Christian Goddesses’ (the key words I used in the search).

I became fascinated by several sentences in the manuscript which scholars had failed to translate. With a Coptic dictionary compiled by one of the translators and a splattering of undergraduate ancient Greek, I undertook to make my own translation of these sentences. My BA was in Linguistics and I could see that the sentences did not present the expected syntax and that the groups of vowels were often repetitive. The Moscow Library of Foreign Literature was also undertaking a translation of the Askew Codex into Russian and we made contact. By this point I’d come up with the theory that the ‘sentences’ which often proceeded rituals, led by a resurrected Jesus on the Mount of Olives preaching to his disciples, were a form of Christian mantra along the lines of Hindu or Buddhist mantra – and that these groups of sounds had no semantic meaning, but were repeated in order to take the devotees into a trancelike state, or prevent the mind from ‘thinking.’ Dr Nersessian agreed that the mantra idea was plausible.

All of a sudden, I was no longer in the British Library reading room, but in an ancient scriptorium....

If these ‘untranslatable sentences’ were early Christian mantra, I wondered which people held this book sacred – how did they use this mantra, and for what end? The writings in the manuscript have been attributed by scholars to early Christian Gnostic groups – suggestions include the Valentinians, the Ophites and, the Sethians, to name a few. Fiction benefits from simplification and so I decided on the Ophites (called the ‘Snake People’ in the novel). I set out to recreate the Ophite group. In fiction, unlike history, one aims at delivering an emotional truth, or a truth that historical speculation alone cannot reach – I wanted to ‘show’ the emotional and experiential spiritual relationship of a group who held these writings sacred; it mattered less which group I chose. The Moscow Library of Foreign Literature invited me to present a paper on how I would do this, which prompted longer hours with the manuscript to ponder how these ‘mantra’ might have been incorporated into ritual practice.

It was after a long day in the Oriental Reading Room in 2004 that I had a vision: the novel, its atmosphere, its urgency and required pace, its main two characters – in a snapshot. Guessing at the pronunciation of Greek letters – αοι αοι αοι (aoi aoi aoi) – I repeated them in the fashion my experience of Buddhist and Hindu meditation had taught me. All of a sudden, I was no longer in the British Library reading room, but in an ancient scriptorium: scrolls were stacked on shelves and between rows of writing desks, and a fat man in a toga rushed towards me with a scroll in his hand saying, ‘take the book and run’. An atmosphere of urgency and impending doom – and smoke filled the scriptorium. He was shouting at a youth in a tunic, who replied: ‘I’m not leaving you’. Love filled the space between them.

Then I was back in the Oriental Reading room with a sensation like jetlag, as if I had travelled a vast distance. My imagination brought something back with me – the voice of Rufius.

Writing Rufius

To write Rufius I undertook a PhD, which specialised in ancient Roman sexuality in literature, and devised a model-based literary composition tool, which I called the ‘pivot of authenticity.’

To write Rufius I undertook a PhD, which specialised in ancient Roman sexuality in literature, and devised a model-based literary composition tool, which I called the ‘pivot of authenticity.’

The first obstacle faced in the writing of Rufius was one of history. In fact, history nearly prevented the novel from being written at all. When research suggested that the voice of the portly man in the scriptorium (the character who has since been named Rufius) was likely speaking from ancient Roman Alexandria, I tried to ignore it for one reason: I knew nothing more than the general reader about the ancient Roman world – that is, nothing more than a handful of Hollywood films, school trips being marched around Roman villas and GCSE Virgil (and basic undergraduate ancient Greek). Ancient Roman novels were written by classical historians, or writers with knowledge nearing that magnitude, which put this novel out of my scope. How would I ever know whether I had achieved the level of authenticity (or rather plausibility) integral to the voice?

In her reflections on Memoirs of Hadrian, Yourcenar states: ‘It took me years to learn how to calculate exactly the distances between the emperor and myself’ [2]. This sums up the challenge contemporary novelists face when calculating the distance between modern readers and ancient Roman culture. It seemed I was not alone in grappling with how to represent the ancient past.

I devised a measuring gauge to judge the distance between modern readers and the perception of ancient Rome in fiction. The ‘pivot of authenticity’ measures the relationship between the author’s aim with respect to historical authenticity and the reception of the reader. It provided a gauge to check consistency in Rufius’ aim for plausibility, and acted as a compass when deciding my point of departure from the primary sources, as well as providing a rough measurement of perceived distance when deciding where to pitch the novel in terms of characterisation, voice, gender and sexual identity, anachronism, and tone pertinent to the milieu of fourth century Alexandria.

Modern novels of ancient Rome are displaced in terms of time, language and authorship – which demand different degrees of anachronism. To bridge the gap in time, novelists shift the ‘pivot’, often overlaying modern morals and sexual norms on to their ancient Roman characters. The credulity of the reader, their willingness to suspend their disbelief, and their knowledge of history will alter the position of the ‘pivot of authenticity’. There could be any number of reader types, although generalisations are useful. To write Rufius, I considered the general reader (with only general knowledge of the ancient world) and the classical historian, but in terms of ancient Roman sexuality, I judged the ‘pivot’ from the academic perspective.

After the pivot was set for composition purposes, the author-reader contracts were established. Vague boundaries then hung around the historical sources; if I strayed too far from them, I was in danger of breaking that contract.

The relationship of the novel with the classical historian seeks the result that this expert reader would not be jerked from the flow of the story to reflect on the implausibility of the behaviour of the characters in a world he knows intimately. It does not seek to perform a pedagogic function, simply to avoid irritation. However in some instances, the novel speculates on historical possibility where there is insufficient evidence to forge a credible historical argument. An example is the existence of Gnostic Christians in fourth century Egypt, and assigning the Pistis Sophia to the Ophites as their sacred book. By the fourth century, the Ophites had not been heard of for at least a hundred years, but I played with the idea that they may have gone into hiding as a result of the laws condemning heresy and growing dangers of extremism as the Orthodox bishops’ power increased. My fictional speculation was aligned to archaeological speculation. Archaeologists found evidence on 2011/2012 digs that dated red crosses in cave communities in Egyptian deserts to the fourth century AD [3]. The evidence is too limited to draw any academic conclusions as to whether or not these are Gnostic. I decided to trust my intuition and assign the Pistis Sophia to the Ophites. When one talks of intuition, one instantly departs from the sphere of academia, and enters the realm of the imagination. There may be some valid points of research that might lead both academic and novelist to speculate about the existence of fourth-century Gnostics in Egypt, but the two will part ways at this point. The novelist will venture forward; the archaeologist will return to the dig with his spade to look for more evidence. [[[quote-5 left]]]

Where firm evidence existed, however, I stuck to the historical sources. When writing about the destruction of the Serapeum, the contemporary historical sources were only of limited use. Several conflicting accounts of the events leading up to and including the destruction of the Serapeum in 391 AD have survived. The two contemporary accounts are from the Christian historian Rufinus’ Ecclesiastical History and the pagan historian Eunapius’ Lives of the Philosophers. Neither of them were eyewitnesses. There are other historians (Socrates, Sozomen and Theodoret) who wrote about the destruction of the Serapeum, but were not contemporary to the events. It is probable that the Christian accounts are as hyperbolic in their exaggeration of bloodshed as is Eunapius’ conflicting insistence that the soldiers met with no pagan resistance when they attacked the statues in the Serapeum. My only firm conclusion of the historical sources is that the two contemporary accounts are so starkly in opposition that neither of them present the actual events – so I speculated that truth resides somewhere between the two. I added elements from Socrates and Sozomen’s later accounts (although I doubt their veracity) to add some ‘pagan spice’.

The contract with the general reader in Rufius has a pedagogic function, particularly in terms of ancient Roman sexuality. What the classical historian will receive as established knowledge, general readers might find exotic and new. Most people do not question the sexual paradigm of the twenty-first century in the West. If the novel were being written solely with the classical historian in mind, certain assumptions about knowledge of the ancient Roman sexual schema could be made and the use of Latin would not need elaboration. Writing with both audiences in mind, I wrote for the reader who will view Rufius as homosexual in the modern sense. Therefore the ancient semantics of the word cinaedus had to be ‘explained’, and ‘shown’. Cinaedus is the only Latin word used in Rufius, with the exception of toga virilis [4]. This choice was made with the general reader in mind, to create a focus on this word, and avoid approximating it with an English equivalent.

My approach to research also included interviewing authors about their aims – rather than extrapolating those aims and speculating solely from their body of work. Very few literary theorists (Jerome De Groot being an exception to some extent) have sought to interrogate authors directly regarding the act of composition. To be fair, it would require a medium to interview Scott, Proust and Stendhal. Even in the case of living authors, theorists tend to draw certain logical and sensible conclusions based on the end product. However, creativity does not rely on logic alone; the required skill is to go beyond logic and access the imagination, then to present it in a framework with the appearance of logic (i.e. a book). Jerome De Groot speculates based on logic when he states: ‘this scrabbling of authors to cover themselves has various motivations …’ [5] and goes on to explain what the authors’ motivations were in writing an Author’s Note. All of his assumptions are highly likely, but Jerome De Groot cannot know the authors’ motivation for certain without asking them directly. He can only speculate. For example, one could assume that Allan Massie’s Author’s Note to Tiberius – ‘In 1984 the autobiography of the Emperor Augustus was discovered in the Macedonian monastery of SS Cyril and Methodius’ [6] – was intended to add authenticity, or the appearance of it. In interview he dispelled any such speculation by saying any reader who thought it true must ‘be very credulous’ [7]. He was having a bit of fun.

Novelists ‘play’ with history. Although literary theory did not influence the process of composition of Rufius, the research of classical historians did. Without research of the classical historians, as well as the guidance of modern historians including ecclesiastical historian Dr David Bagchi and experts in ancient Roman sexuality - Dr Craig Williams, Dr Kelly Olson ('fashionista of the ancient Roman world'), Tom Sapford (cinaedi and music) and Dr Jennifer Ingleheart, to name a few - Rufius could not have achieved its aim of historical plausibility. Modern novelists of ancient cultures are not so far removed from some ancient historians in antiquity – if we don’t know, we make it up!

To write Rufius I became a part of the Classics community and presented papers at Classics conferences (something initially very daunting). Since publication, I’ve been invited to talk at events about the relationship between art and history. At the Petrie Museum’s LGBT History Month 2016 Objects of Desire, I discussed how I used ancient objects from archaeological digs in Egypt as inspiration for writing Rufius.

Writing the cinaedus

The voice I heard in the British Library initially made me think Rufius was gay – a camp, flamboyant queen. After my initial research into ancient Roman sexuality, I realised that Rufius was a cinaedus. I decided that I would not only bring to life the ancient Gnostic group, but that I would attempt something far more challenging – to resuscitate the extinct gender / sexual identity of the cinaedus for a modern readership.

Cinaedus is often translated into English as ‘catamite’, but it took me a novel to demonstrate the meaning of the word, which loses its sense when separated from its social context.

Cinaedus is often translated into English as ‘catamite’, but it took me a novel to demonstrate the meaning of the word, which loses its sense when separated from its social context. Cinaedus comes from kinaidos, the Greek word for an “effeminate buggeree”. A cinaedus was an adult male who dressed effeminately and wore make-up, and the Latin insult implied that he was the receptive partner. The ancient Romans defined their sexuality – not on a spectrum with gay at one end and straight at the other – but as whether you conquered, or submitted. If you were a rich adult man, you were expected to conquer and penetrate. According to many, it was a social outrage to deviate from the hard ideal of Roman masculinity, wear make-up and bend over for your pleasure. In 390 AD, a law was passed which sentenced cinaedi to death by public burning.

The voice of Rufius (as I later named the portly Roman in my British Library vision) came practically ready-formed. I added speech tags like ‘by Bacchus’ as the research progressed. The shape of the character of Rufius was not far off either – a lot is carried on a voice and first impressions, as anyone who has ever interviewed will know. Humans judge one another in an instant, and as books like Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink tell us, these judgements are more than knee-jerk reactions. It was thus with Rufius. In the short moments of my vision, I felt him: his reluctant courage, his hedonism, his trangressive, to-Hades-with-it nature, and his love of life’s comedy. All this in the blink of an eye. I knew instantly that if I could muster the creative skill to put him on paper, Rufius was strong enough to carry the story that had been forming around the Gnostic Christians of Egypt and the fall of the Serapeum and a vast chunk of the Great Library of Alexandria.

It is difficult to reconstruct the creative processes which led me to rendering Rufius’ character into the fully-formed shape he takes in the novel. Rufius emerged from a combination of the voice I first heard in the British Library, a social life in the gay community, reading gay literary fiction, and laughing at Kenneth Williams’ rendition of Julius Caesar in Carry on Cleo [8]. (It was only after doing the research into ancient Roman sexuality that I realized Rufius wasn’t gay; Rufius was a cinaedus. If Suetonius’ The Lives of the Twelve Caesars is based on more than just rumour and gossip, Kenneth Williams was perhaps a better choice than more brawny actors who have been cast to play Caesar in film and TV).

I was privileged to have access to the latest research and to discuss ‘off the academic stage’ what historians speculated about, but didn’t dare write in academic journals as the speculation lacked the rigour required by the academy. Perfect for fiction. My gratitude to the historical experts who humoured my questions is immense – without their generosity to engage with me in speculation, Rufius would have been a far more two-dimensional, stereotypical character, heavy with historical research, but lacking the human ‘messiness’ of real life sexuality and gender identity.

Although ancient Roman literature, theatre and poetry inform us of ancient Roman attitudes to cinaedi – ‘a catamite (cinaedus) entered, the stalest of all mankind’ [9] – we have no first person statements from a cinaedus in Roman antiquity. Cinaedus was a word used as an insult, like the words faggot or bastard in modern English. Although men were generally their preference, cinaedi were sometimes interested in women; their sexual (and general) excess was the problem. Before deciding Rufius’ preference, I asked one of the world’s leading experts in ancient Roman sexuality in interview, Dr Craig Williams, whether he thought it plausible that a cinaedus might be interested in an adolescent on the cusp of adulthood (as there was an adolescent in my British Library vision). He thought it plausible and worth exploring. Fiction is an ideal vehicle to explore this type of speculation, and for the creation of rounded fictional characters it is a good idea to veer away from stereotypes.

Williams suggests that behind every description of a man as a cinaedus ‘lurked the image of the gallus’ [10], the emasculated Priest of Cybele, as well as the image of an Eastern ceremonial dancer. So the word cinaedus carries with it the sense of performance. The cinaedus, pathicus and effeminatus stood in stark contrast to the ideal Roman male, and was a stock comic character, as we can see from Petronius’ Satyricon, and the poetry of Catullus, Martial and Juvenal. As Aeson (Rufius’ lover) watches Rufius playing up to his stereotype, he muses over the mixed feelings society has towards these ridiculed, condemned, as well as comic figures.

‘Come on, cinaedus. Show us what you’ve got.’ A woman hangs out of a first floor window and heckles like she’s at the theatre.

The cinaedus pouts his lips, puts his hand on his hip and lisps, ‘At least I don’t look like Venus after a night on the town with Bacchus, dear.’

I can never work out if people love or hate the cinaedi.’

Rufius

p. 48

When I asked his opinion in conversation, Williams agreed with the idea that it was plausible to explore further in fiction the idea that some ancient Romans might be endearing towards cinaedi. The Egyptologist J.J. Johnson pointed out in an interview about Rufius at London’s Petrie Museum (Objects of Desire, LGBT History month 2016) that in most ancient texts cinaedi are represented as prostitutes and carve out sad figures. That is the case, but although Rufius’ rendering was influenced by the ridiculed cinaedi of the ancient sources, I was intrigued by the story in Suetonius’ The Lives of the Twelve Caesars in which Julius Caesar was ridiculed by his political opponents (and the people, if we take the graffiti and legions’ songs into consideration) for being a cinaedus, but maintained his status as emperor. Caesar denied being a cinaedus. But what if we had a man with nothing to lose, a man who openly presented as a cinaedus and took the taunts on the chin? Add to that a man who had his own money through inheritance. The Romans were materialists. Money talked. A cinaedus could never wear the thick purple stripes of the Senate and take up public office – but what if he couldn’t care less? What if being authentic were more important to him than his social status? In short, I researched thoroughly then played with the material and speculated.

After years of reading, attending Classics conferences and interviewing experts in the field of ancient sexuality and ethics, I was presented with a problem: the general reader would assume Rufius was gay as I had. Jerome De Groot emphasises the influence of television and film on the readers of historical fiction:

We might suggest that the cultural forms of history and memory such as film, television or literature are extremely influential in creating and sustaining a particular type of historical imaginary, and one which is probably at odds with or at least a simplified version of the historical ‘reality.’

De Groot

p. 49

Television is the most ubiquitous entertainment medium in Western culture. As Jerome De Groot asserts, the general audience is naturally influenced by the representations of history viewed on screen. We can see this even in novels where the ‘pivot of authenticity’ is at the more ‘authentic’ end of the spectrum, like Allan Massie’s and Steven Saylor’s novels.

Steven Saylor and Allan Massie both adhere to the primary sources but draw on familiar modern imagery to develop character and voice. In turn, ancient Roman gender identities become accessible thorough echoes of the familiar in our own culture. That this approach was common to two veteran authors who both aim at the appearance of authenticity (their approach was acknowledged in interview [11]) dispelled my concern about the anachronism that I suspected might be creeping into my rendering of the character of Rufius. I was concerned he sounded too modern, too high camp – a type we are accustomed to seeing on television. However, that familiarity is exactly what was needed to ease the general reader into identifying with the lost identity of the cinaedus.

Rufius’ speech tags ‘dear’ and ‘by Bacchus’ draw on the diction of an old ‘queen’ in the modern sense, as well as reminding the reader that Rufius is a hedonist, a pagan, and at odds with the ethos of Christianity. On one level, he represents the dying pagan world – Julius Caesar’s first-century BC world may have accepted his rumoured gender deviance, but in the era of the Christian emperors, tassels on tunics wouldn’t be tolerated.

For modern Westerners, as for ancient Romans, there is a preoccupation with what constitutes masculinity, and what is acceptable behaviour for a ‘real’ man.

Next, I needed to present what a cinaedus would have looked like. A cinaedus is a man ‘whose eyebrows are shaved off; who walks around with plucked beard and thighs … who is fond of men as he is of wine’ [12]. I was lucky enough to meet Dr Kelly Olson, an expert in ancient Roman dress, at a conference. Olson describes how a cinaedus dressed: ‘The cinaedus was a man who wore loose colourful clothing, perfume and curled hair, who walked along with a mincing gait, and who was apt to be anally penetrated and enjoy it.’ [13]

For modern Westerners, as for ancient Romans, there is a preoccupation with what constitutes masculinity, and what is acceptable behaviour for a ‘real’ man. As long as the general reader can grasp the perceived importance in antiquity of ‘real’ men being ‘active’, and the social stigma of being ‘passive’, they will move closer towards the ancient Roman sexual paradigm.

So now I had the voice, knew what Rufius looked like and how ordinary Romans might view him. Considering the importance of the context (the fall of paganism), I needed to research how Christians (the orthodox type in the context of rising extremism) might view him. Under the Christian emperors, the laws against cinaedi and pathici increased in severity. A new law was promulgated on 6 August, 390 AD (so during the period in which the novel is set), which condemned cinaedi to public execution: ‘All persons who have the shameful custom of condemning a man’s body, acting the part of a woman’s, to the sufferance of an alien sex (for they appear not to be different from women), shall expiate a crime of this kind in avenging flames in the sight of the people’ [14].

Although there is plenty of evidence for accusations in political texts, poetry and graffiti, I found no evidence of any ancient trials having taken place. I speculated that as this crime is practically impossible to prove – as with section 377 of Indian law which, put simply, criminalises anything other than the missionary position between heterosexuals – this Roman law might have been used to blackmail cinaedi as section 377 allegedly has been used to blackmail ‘hijra’ (transgender people) in modern India.

It was important to depict ancient Roman attitudes towards cinaedi as early on as possible, so as to avoid the reader assuming that being ‘gay’ in the modern sense was the problem. To communicate this complex information without boring the reader I showed other characters’ attitudes to Rufius. Here is an extract showing Aeson’s first impression of Rufius when they meet on Venus Street:

The fat Roman has a cinaedus’ lisp, but his voice is deep, not high like a woman. Hand on his hip … he must be the cinaedus Lanky mentioned. Usual curled hair and eyebrows painted on like a eunuch, but there’s something different about him …’

Rufius

p. 48

Rufius’ character development may have borrowed something from modern film and television to help reader identification, but I wanted the reader to view him as ancient Roman, operating in an ancient culture. Rufius is a pagan from the privileged patrician class; he is a hedonist, with a big intellectual ego. His ego is seen tête à tête with another big ego: the Archbishop’s. In Chapter 36, the characters of Rufius and Archbishop Theophilus of Alexandria offer a glimpse of the battle between two dominant ‘religions’ of the era (paganism and Christianity) through the pinhole of their personal power struggle.

‘Enough, Rufius! You mock the church, you mock the Empire, you mock mankind … Harbouring heretical books is the reason I am here. Your motivation does not interest me. Nor will my inspectors be interested in the protests of a cinaedus. I can pin you down with heresy or infamy.’

‘Oooo! Pin me down!’ A swing of the hips is in order. ‘Bring on your inspectors, Bishop. This old Roman could do with a little fun.’

Rufius

pp. 267-68

Rufius is an ancient Roman, with elements borrowed from modern culture in order to enable the reader to identify with him, but as in the case of Sir Walter Scott’s characters, my aim is that his inner life is historically authentic to a large degree. The decision to use the Latin word cinaedus throughout the novel rather than find an English equivalent – the closest being ‘an effeminate buggeree’ [15], ‘catamite’, or ‘passive male’ [16], or the even more academic and somewhat clinical term, ‘receptive partner’ – is to retain the historical context and avoid layering the modern sexual paradigm on to the ancient one. I would hope that the use of this obscure Latin insult also adds to the general reader’s pedagogic satisfaction. One of the joys of reading both history and historical fiction is a release from the narrow confines of one’s own culture. My aim was for the character of Rufius to be a vehicle for entertaining time travel. In a recent interview in Brighton Waterstones [pictured left], I was delighted to be asked by two members of the audience for a sequel – they both wanted more of the character of Rufius. He’s a rogue, and utterly immoral by our own standards, but some readers love him.

Rufius is an ancient Roman, with elements borrowed from modern culture in order to enable the reader to identify with him, but as in the case of Sir Walter Scott’s characters, my aim is that his inner life is historically authentic to a large degree. The decision to use the Latin word cinaedus throughout the novel rather than find an English equivalent – the closest being ‘an effeminate buggeree’ [15], ‘catamite’, or ‘passive male’ [16], or the even more academic and somewhat clinical term, ‘receptive partner’ – is to retain the historical context and avoid layering the modern sexual paradigm on to the ancient one. I would hope that the use of this obscure Latin insult also adds to the general reader’s pedagogic satisfaction. One of the joys of reading both history and historical fiction is a release from the narrow confines of one’s own culture. My aim was for the character of Rufius to be a vehicle for entertaining time travel. In a recent interview in Brighton Waterstones [pictured left], I was delighted to be asked by two members of the audience for a sequel – they both wanted more of the character of Rufius. He’s a rogue, and utterly immoral by our own standards, but some readers love him.

The other major challenge I had was that it was imperative that Rufius did not succumb to stereotype if I wanted to deliver one of the messages in the novel: in Rufius' own words, ‘One’s sexuality is as individual as a fingerprint’ (Rufius, p. 116). It was my goal that Rufius didn’t simply satisfy the standard stereotype for a cinaedus (an effeminate buggeree), but that the novel showed the messiness and idiosyncrasies of sexuality. Although my research led me to believe cinaedi would on the whole wish to be penetrated by the antithesis of themselves (hairy men), we know from gender research over the past forty years that sexual preferences and gender identity are also highly individualised. The majority of cinaedi may have fancied ‘manly’ men, but, as in real life, human sexual preferences are not defined according to strict categories. Rufius likes adolescents on the cusp of manhood, those youths who will become hairy men, manly men, like Aeson. As noted earlier, research demonstrates that some cinaedi had relationships with women.

As pederastic relationships were acceptable to the ancient Romans (as long as the youth showed signs of physical maturity), I had to show that the characters didn’t have issue with the relationship between Rufius and Aeson on this count. Rufius needed to be free of the type of moral tension that we see in Nabokov’s Lolita if I were to achieve my aim: to show sexuality through the ancient Roman lens. The moral judgement is instead directed towards Rufius’ gender deviance, not his choice of lover.

Rufius - the sequel

I have been asked by readers at two Waterstones’ events and the London Launch at Gay’s the Word bookshop if there will be a sequel. I did not originally envisage writing a sequel, but since I didn’t have the heart to kill my favourite character off at the end of the novel, it is possible – although that’s not my current focus.

I am currently editing the novel I was writing when I was so rudely interrupted by Rufius – The Hostess Detective. I am also developing some ideas about Saint Damasus and Saint Jerome and the writing of the new Vulgate bible. So much fascinating research falls by the wayside when writing a historical novel, as the loyalty must be to the story. The editorial process for Rufius resulted in the chapters with Damasus and Jerome being chopped – and the novel has benefitted in terms of pace and flow – for I was looking to write ‘an action book’, not a heavy historical drama. I wanted a fast-paced read and the Saint Jerome chapters had to go. It is a better book because of it, but it hurt to delete those chapters, which I spent eighteen months researching. So, there might be a novel about Saint Damasus and Saint Jerome in the future.

Notes

[1] The Pistis Sophia (Egypt, c. 200-300 AD) is unlikely to be the original title, but the manuscript is referred to as such due to one of the scribes scribbling this in the margin.

[2] Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian (London, Penguin, 1959), 271.

[3] From a conversation with archeologist Dr. Gillian Pyke at the ‘Pagans, Christians and Muslims: Egypt in the First Millennium AD’ conference, British Museum, July 9, 2012.

[4] Toga virilis is used to add another layer of meaning to the reader’s understanding of cinaedus – namely that cinaedi never mature into wearing a man’s toga. In a sense, a cinaedus is the eternal boy.

[5] De Groot, 9.

[6] Allan Massie, Tiberius (London, 1990), 15.

[7] Allan Massie, Edinburgh Interview with Sarah Walton: Summerhall Historical Fiction Festival (Edinburgh, 2013) [website] The University of Hull <https://hydra.hull.ac.uk/resources/hull:8372>, 1:45.

[8] Carry on Cleo, Gerald Thomas, dir. (Pinewood Studios: Anglo-Amalgamated Productions, 1964) [Film].

[9] Petronius, The Satyricon, (Gutenberg EBook produced by David Widger, 2006), 23.

[10] Williams, Roman Homosexuality (1999), 177.

[11] Steven Saylor, San Francisco Interview with Sarah Walton: Bouchercon Crime Writing Conference (San Francisco, 2010) [website] The University of Hull <https://hydra.hull.ac.uk/resources/hull:8374>

Allan Massie, Edinburgh Interview with Sarah Walton: Summerhall Historical Fiction Festival (Edinburgh, 2013) [website] The University of Hull <https://hydra.hull.ac.uk/resources/hull:8372>

[12] Williams, Roman Homosexuality, 23. This was an attack by the consul Scipio Aemilianus in 147 B.C. against a certain P.Sulpicius Galus.

[13] I am grateful to Dr Olson who shared with me a draft of her paper, ‘Masculinity, appearance, and sexuality: Dandies in Roman Antiquity’ prior to publication in the Journal of the History of Sexuality.

[14] Theodosian Code and Novels and the Sirmondian Constitutions (ed.) Pharr, C. (USA: Princeton University Press, 1957).

[15] Walton, S. Rufius, (London: Barbican Press, 2016), Historical Note, p. 411.

[16] Amy Richlin, ‘Not before Homosexuality: The Materiality of the Cinaedus and the Roman Law against Love between Men’. Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol 3, No 4, (USA: University of Texas; Apr, 1993), 529.

Find out more....

Rufius is available in the UK & USA in paperback and eBook: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Rufius-Sarah-Walton/dp/1909954160

You can discover more about Sarah’s work on her website: www.sarahwalton.org

Watch Olivier Award-winning actor, Christopher Green [pictured below, third from left] as Rufius at London’s Southbank: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gTww8SjH9-o

Rufius adapted as a monologue for the stage for Polari on Tour, October 2016. Rufius is played by Tony Leonard, pictured below (photograph by Richard Peacock) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rkzyvs-XdvY&feature=youtu.be