Unleashing State Hell: Attica 50 Years On

Joe Sim - Professor of Criminology - Liverpool John Moores University

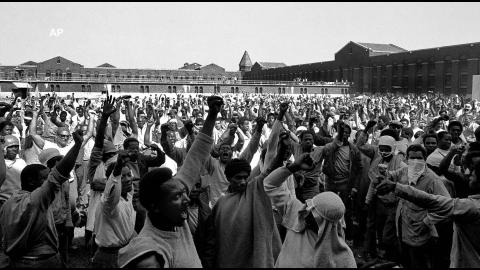

The 50th anniversary of the barbaric suppression of the Attica prison uprising occurred on September 13th 2021. The uprising, and the ferocious response by the American state, whose agents shot dead 43 prisoners and hostages, had a seismic impact on the radical prisoners’ rights movement which was emerging in the UK, and internationally, at that time, a movement which remains central to the struggles around prisons today. Attica brutally illustrated the terror and violence the state could mobilise when its legitimacy was challenged, the cheapness of prisoners’ lives and the blatant hypocrisy of a system that claimed to be rehabilitative but which was, in practice, based on the systemic delivery of punishment and pain. The punishment and pain experienced by Black prisoners was underpinned by institutionalised, racist dehumanization and degradation. A culture of almost complete immunity and impunity protected those who were responsible for the carnage aided and abetted by an uncritical, supine mass media.

Below is a review of Heather Ann Thompson’s magnificent book Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy which was published in 2016. The book systematically details the devastating events at Attica and the brutal aftermath. It provides a fitting and elegiac testimony not only to the dead and the survivors but also to their relatives and friends as well as shining a shimmering and unforgettable light on the endurance of the human spirit.

Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy by Heather Ann Thompson Pantheon Books[i]

Joe Sim

According to Franz Fanon, ‘we revolt simply because, for many reasons, we can no longer breathe’.[ii] Fanon’s insight is directly relevant to the barbaric events which unfolded at Attica prison in New York State in September 1971 when prisoners revolted against the suffocating conditions of their confinement. For four days they controlled the institution from D Yard before the state unleashed hell and launched a ferocious assault to retake the prison. The attack left 43 prisoners and hostages dead and 128 wounded, many seriously. Heather Anne Thompson’s monumental, haunting and deeply moving study, based on 10 years of meticulous research, provides a compelling analysis of the roots of the revolt, the brutal, remorseless revenge enacted by the state, the deceit and lies peddled to cover up how the prisoners and hostages died and the iron resolve of survivors and the families of the dead prisoners and hostages to achieve ‘truth, justice and accountability’.[iii] It is a story of institutionalized violence and torture, deeply embedded racism and state collusion, conspiracy and cover-up which has taken 45 years to finally bring into the light.

Why did the revolt happen? Its roots lay in the challenges posed by the civil rights movement and the increasing influence of the Black Panther Party, many of whose members were confined in Attica and who refused to accept the degrading treatment, casual sadism and systemic racism dispensed on a daily basis. Conditions were appalling. Prisoners were given one bar of soap each month and one roll of toilet paper which meant that they had to ‘limit themselves to ‘one sheet per day’. Expenditure on food amounted to ‘a mere 63 cents per prisoner per day…’ (p. 8). The book is based on a range of unpublished sources and documents which were stored, often dismissively, in boxes and store-rooms around the USA. Among the items Thompson discovered were the still-bloodied clothes of L.D. Bartley whose rousing and defiant oratory poignantly articulated the perspective of the prisoners: ‘We are men. We are not beasts and we do not intend to be beaten or driven as such. The entire prison populace, that means each and every one of us here, has set forth to change forever the ruthless brutalization and disregard for the lives of the prisoners here and throughout the United States. What has happened here is but the sound before the fury of those who are oppressed’ (p. 78). His defiance cost him his life when he was killed after the prison had been retaken. His, and the other deaths, were a direct result of the devastating and illegal firepower mobilized by the state.

The assault on D yard was led by troopers who were ‘armed with .270 caliber rifles, which utilized unjacketed bullets, a kind of ammunition that causes such enormous damage to human flesh that it was banned by the Geneva Conventions’ (p. 157). Between 2,349 and 3,132 lethal (shotgun) pellets were fired. There were also 8 rounds fired ‘from a .357 caliber, twenty-seven rounds from a .38 caliber, and sixty-eight rounds from a .270 caliber….these counts did not even include the bullets from correction officers and other members of law enforcement not fully accounted for’ (p. 526).

The relentless brutality of the state’s assault was not the result of deranged individuals engaging in renegade behavior — the politically reductive and theoretically naïve ‘bad apple’ theory of state deviance propagated by an endless procession of politicians, media personnel and academics, linked together by a positivist, umbilical cord which defines state actions as inherently benevolent which are occasionally tainted by the activities of a pathological few. Rather, terror, torture and brutality were systemic to the state’s brutal response. This was based on a process of conspiratorial, racist collusion which was integral to the actions of those who were on the ground on the day relentlessly abusing and killing prisoners and hostages and which moved remorselessly up through the ranks of the police, and state troopers, into the offices of the prosecuting authorities and finally to the highest reaches of the US government itself whose views were mobilized to legitimate the brutal actions of those on the ground.

As Nelson Rockefeller, the state governor, mendaciously told a grateful President Nixon in the aftermath of the state’s assault, ’the whole thing was led by the blacks’ and that state troopers had been deployed ‘only when they [the prisoners] were in the process of murdering the guards’ (p. 200). As ever, when the state kills, its agents are immediately deployed to spread lies, and engage in deceit, exaggeration and distortion, a toxic mix designed to both mystify what happened and to mobilise a narrative for media and popular consumption that the violence of its servants was, given the dangers they were facing especially from black prisoners, legitimate.

Yet, as the book makes abundantly clear, even at the height of the carnage in D Yard, it was not the prisoners — pejoratively labelled as liars, psychopaths and animals — who were murdering the hostages. Rather, prisoners attempted to safeguard them while putting their own lives in grave danger. However, even this selfless act of bravery and humanity was buried under the weight of the perfidious deceit of the state’s spokespersons who unashamedly peddled the lie that the hostages had had their throats cut or had been castrated by the very prisoners who had attempted to protect them. The pitiless response to the prisoners, and the unshackled violence they experienced, was based on the scornful, mortifying and degrading vilification of their helpless bodies, dead and alive. According to one eyewitness, Tommy Hicks, a prisoner who was still alive after the prison was retaken, was ‘“hit with a barrage of gunfire” after which he saw troopers walk over to Hicks’s body take “the butt end of the gun, pound the flesh in the ground, kick it, pound it, shoot it again”’. Survivors were made to crawl naked through a mud-filled yard towards state servants where they were savagely beaten.

This brutality extended even to the most severely wounded who were given no sedatives and who were ‘expected to suffer through the pain’. In contrast, state troopers, whose injuries included a ‘fractured finger, bruised knee [and] a fractured toe’, were prioritized (pps. 206–7). The role of medical staff before and after the revolt, and their abject capitulation to the state’s dehumanizing goals, is made abundantly clear in the book. They were active agents in the brutalization of the prisoners. Thompson beautifully crafts the forgotten and moving story of the survivors into a devastating indictment of the naked exercise of power from state servants who acted with total impunity before, during and after the revolt towards them. The chilling calculation around life and death extended to its own surviving, employees who were only paid for eight hours for each day they were held hostage as the rest of the time ‘they were technically off the clock’ (p. 538).

The campaigns by the survivors and families, spread over nearly half a century, demanded a reckoning with state servants, whose every action, despite the occasional, honorable, individual exception, was built on denying truth, subverting justice, intimidating those who disagreed with the dominant narrative, burying and destroying evidence, destabilizing different campaigns and attempting to ensure that those responsible for the carnage would escape justice. This was done through ‘refusing to hand over materials expeditiously — even when required by law to do so…..’ (pps. 315–316) and ensuring that funding was minimal for lawyers who were acting for the families. The book concludes by focusing on the legacy of the revolt.

The liberal, humanizing reforms proposed by the state quickly dissipated under the collective, regressive weight of resurgent law and order campaigns, the ongoing war on drugs, the hostility towards prisoners and the drive towards mass incarceration through a racist process of criminalization which targeted the powerless while leaving the powerful, as ever, free to engage in rampant acts of criminality. Mass incarceration legitimates institutionalized racism and institutionalized racism legitimates mass incarceration while the police and the courts provide the glue that holds the whole, racist edifice together. And yet collective webs of resistance still persist. The strikes which took place in late 2016 across 22 prisons — the biggest in US prison history — against slave labour conditions, links directly back to Attica. So too does the principled activities of Black Lives Matter contesting the ongoing, systemic racism, and state-induced death, disproportionately experienced by African Americans.

Nearly half a century on, the aching desolation generated by the barbarity perpetrated by the state at Attica still lingers in all of its melancholic toxicity. At the same time, the righteous anger and the relentless desire to ensure that Attica is not forgotten, is an eloquent testimony to the human spirit’s enduring sense that injustice needs to be confronted, wrongs righted and responsibility attributed. Voltaire’s famous quote — ‘to the living we owe respect but to the dead we owe only the truth’ — provides a fitting tribute to all of those who have struggled over the last 50 years to right Attica’s wrongs. It is also a fitting testimony to this magnificent book, and to Heather Thompson’s rigorous scholarship and extraordinary commitment which runs like a clear stream from the book’s first through to its last sentence.

[i] This review was originally published in the Prison Service Journal, Issue 231, May 2017, pp 41-44.

[ii] Franz Fanon cited in Kyerewaa, K. (2016) ‘Black Lives Matter UK’ in Red Pepper, Issue 210 October/November 2016 p. 8.

[iii] This is the slogan which the charity INQUEST campaigns around. The charity provides ‘expertise on state related deaths and their investigation to bereaved people, lawyers, advice and support agencies, the media and parliamentarians’ (inquest.org.uk).

This blog has also been published by the Centre for the Study of Crime, Criminalisation and Social Exclusion at Liverpool John Moores University, see https://ccseljmu.wordpress.com/