It has been quite a week. On Wednesday I sat on the edge of my seat in the Berrill Lecture theatre at the UK Open University waiting to see if Rosetta’s lander Philae, complete with the Ptolomy instrumentation developed by, amongst others, colleagues in our Department of Physical Sciences, would make it to the surface of Comet 67P, Churyumov–Gerasimenko. I’m sure that everyone knows by now that it did, and despite the fact that the lander bounced and came to rest in a non-optimal position, some incredible scientific data has been received; so there is lots more for my colleagues to do! Incidentally the photo shows a model of the lander near the entrance to our Robert Hooke building.

It has been quite a week. On Wednesday I sat on the edge of my seat in the Berrill Lecture theatre at the UK Open University waiting to see if Rosetta’s lander Philae, complete with the Ptolomy instrumentation developed by, amongst others, colleagues in our Department of Physical Sciences, would make it to the surface of Comet 67P, Churyumov–Gerasimenko. I’m sure that everyone knows by now that it did, and despite the fact that the lander bounced and came to rest in a non-optimal position, some incredible scientific data has been received; so there is lots more for my colleagues to do! Incidentally the photo shows a model of the lander near the entrance to our Robert Hooke building.

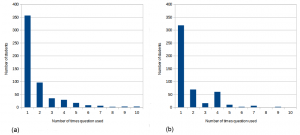

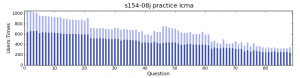

Then on Friday, we marked the retirement of Dr John Bolton, who has worked for the Open University for a long time and made huge contributions. In particular, John is one of the few who has really analysed student engagement with interactive computer-marked assessment questions. More on that to follow in a later posting; John has been granted visitor status and we are hoping to continue to work together.

However, a week ago I was just reaching Schiphol airport prior to a day in Amsterdam on Sunday and then delivering the keynote presentation at Dé Onderwijsdagen (‘Education Days’) Pre Conference : ‘Digital testing’ at the Beurs World Trade Center in Rotterdam. It was wonderful to be speaking to an audience of about 250 people, all of whom had chosen to come to a meeting about computer-based assessment and its impact on learning. Even more amazing if you consider that the main conference language was Dutch, so these people were all from The Netherlands, a country with a total population about a quarter the size of the UK.

However, a week ago I was just reaching Schiphol airport prior to a day in Amsterdam on Sunday and then delivering the keynote presentation at Dé Onderwijsdagen (‘Education Days’) Pre Conference : ‘Digital testing’ at the Beurs World Trade Center in Rotterdam. It was wonderful to be speaking to an audience of about 250 people, all of whom had chosen to come to a meeting about computer-based assessment and its impact on learning. Even more amazing if you consider that the main conference language was Dutch, so these people were all from The Netherlands, a country with a total population about a quarter the size of the UK.

There is some extremely exciting work going on in the Netherlands, with a programme on ‘Testing and Test-Driven Learning’ run by SURF. Before my keynote we heard about the testing of students’ interpretation of radiological images – it was lovely to see the questions close to the images (one of the things I went on to talk about was the importance of good assessment design) – and about ‘the Statistics Factory’, running an adaptive test in a gaming environment. This linked nicely to my finding that students find quiz questions ‘fun’ and that even simple question types can lead to deep learning. Most exciting is the emphasis on learning rather than on the use of technology for the sake of doing so.

I would like to finish this post by highlighting some of the visions/conclusions from my keynote:

1. To assess MOOCS and other large online courses, why don’t we start off by using peer assessment to mark short answer questions. Because of the large student numbers this would lead to accurate marking of a large number of responses, with only minimal input from an expert marker. Then we could use these marked responses and machine learning to develop Pattern Match type answer matching, to allow automatic marking for subsequent cohorts of students.

2. Instead of sharing completed questions, let’s share the code behind the questions so that users can edit as appropriate. In other words, let’s be completely open.

3. It is vitally important to evaluate the impact of what we do and to develop questions iteratively. And whilst the large student numbers at the UK Open University mean that the use of computer-marked assessment has saved us money, developing high-quality questions does not come cheap.

4. Computer-marked assessment has a huge amount to commend it, but I still don’t see it as a panacea. I still think that there are things (e.g. the marking of essays) that are better done by humans. I still think it is best to use computers to mark and provide instantaneous feedback on relatively simple question types, freeing up human time to help students in the light of improved knowledge of their misunderstandings (from the simple questions) and to mark more sophisticated tasks.

The videos from my keynote and the other presentations are at http://www.deonderwijsdagen.nl/videos-2014/