Sadly, I don’t get as much time as I used to in which to think about assessment. So last Wednesday was a particular joy. First thing in the morning I participated in a fantastic webinar that marked the start of a brand new collaboration between two initiatives that are close to my heart – Transforming Assessment (who run a webinar series that I have been following for a long time) and Assessment in Higher Education (whose International Conferences I have helped to organise for 4 years or so). Then I spent most of the afternoon in a workshop discussing peer review. The workshop was good too, and I will post about it when time permits. For now, I’d like to talk about that webinar.

The speaker was Sue Bloxham, Emeritus Professor at the University of Cumbria and the founding Chair of the Assessment in Higher Education Conference. It was thus entirely fitting that Sue gave this webinar and, despite never having used the technology before, she did a brilliant job – lots of good ideas but also lots of discussion. Well done Sue!

Assessment criteria are designed to make the processes and judgement of assessment more transparent to staff and students and to reduce the arbitrariness of staff decisions. The aim of the webinar was to draw on research to explore the use of assessment criteria by experienced markers and discuss the implications for fairness, standards and guidance to students.

Sue talked about the evidence of poor reliability and consistency of standards amongst those assessing complex performance at higher education level, and suggested some reasons for this, including different understanding, different interpretation of criteria, ‘marking habits’ and ignoring or choosing not to use criteria.

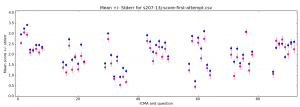

Sue then described a study, joint with colleagues from the ASKe Pedagogical research centre at Oxford Brookes University, which had sought to investigate the consistency of standards between examiners within and between disciplines. 24 experienced examiners from 4 disciplines & 20 diverse UK universities were employed and each considered 5 borderline (2i/2ii or B/C) examples of typical assignments for the discipline.

The headline finding was that overall agreement on a mark by assessors appears to mask considerable variability in individual criteria. The difference in the historians’ appraisal of individual constructs was further investigated and five potential reasons were identified that link judgement about specific elements of assignments to potential variation in grading:

- Using different criteria from those published

- Assessors have different understanding of shared criteria

- Assessors have a different sense of appropriate standards for each criterion

- The constructs/criteria are complex in themselves, even comprising various sub-criteria which are hidden to view

- Assessors value and weight criteria differently in their judgements

Sue led us into a discussion of the implications of all of this. Should we recognise the impossibility of giving a “right” mark for complex assessments? (for what it’s worth, my personal response to this question is “yes” – but we should still do everything in our power to be as consistent as possible). Sue also discussed the possibility of ‘flipping’ the assessment cycle, with much more discussion pre assessment and sharing the nature of professional judgement with students. Yes, yes, yes!

If I have a complaint about the webinar it is purely that some of the participants took a slightly holier than thou approach, assuming that the results from the study Sue described were as a result of poor assessment tasks or insufficiently detailed criteria (Sue explained that she didn’t think more detailed criteria would help, and I agree) or examiners who were below par in some sense. Oh dear, oh dear, how I wanted to tell those people to carry out a study like this in their own context. Moderation helps, but those who assume high level consistency are only deluding themselves.

While we are on the subject of the subjective nature of assessment, don’t take my word for the high quality of this webinar, watch it yourself at http://ta.vu/4N2015