OU News

News from The Open University

- Home

- Artist and Empire: a belated revisiting of our colonial history

Artist and Empire: a belated revisiting of our colonial history

Posted on • Arts

Artist and Empire, the major exhibition showing at Tate Britain, has been well received by art critics and audiences alike. Aiming to unite art and a reckoning with Britain’s imperial past, it is a noteworthy venture – but why has it taken so long for such a show to be hosted by a major British art institution? Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Art, Renate Dohmen, suggests the delay is the result of a historic misconception of what constitutes British art.

As an institution devoted to art from Britain, surely Empire should be central to the remit of the Tate? The belatedness of ‘British Empire’ as the central theme to an exhibition at the Tate is no oversight; it is a reflection of the very history that the exhibition seeks to display.

The Tate has inherited a collection that, for the most part, does not feature art produced by subjects of the British Empire, or by artists who ventured into imperial lands outside Britain.

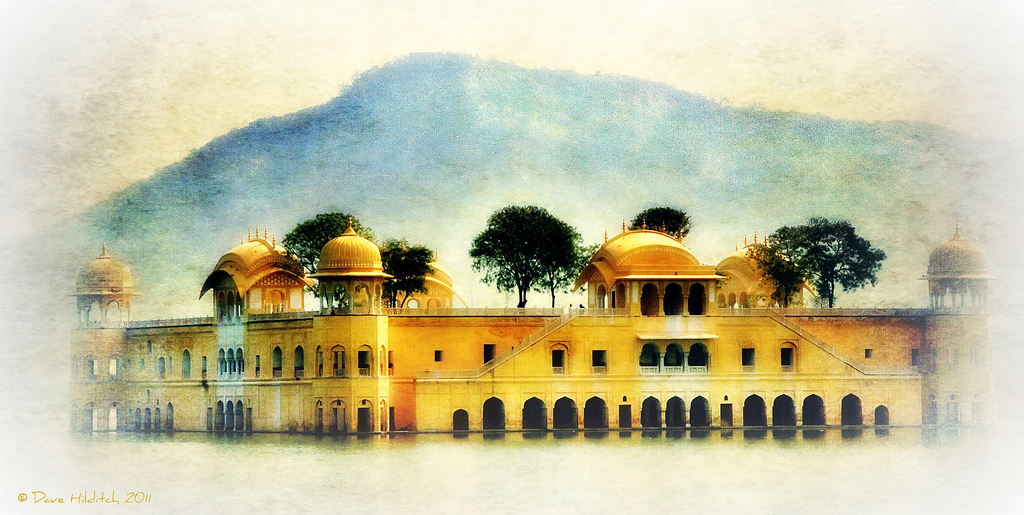

Art from the Indian sub-continent has been deposited in the Victoria and Albert Museum, whose remit is the history of craft and design – reflecting the colonial attitude that the Indian race excelled in the lower aesthetic categories, but was incapable of fine art.

Surprisingly, it is not only paintings executed by ‘natives’ that could not be considered high art; even European artists who depicted exotic scenes from the British Empire generally failed to make the grade. So we find the likes of Hodges’s Cascade Cove, Dusky Bay in the collection of the National Maritime Museum, and Robert Home’s marvellous The Reception of the Mysorean Hostage Princes by Marquis Cornwallis, 26 February 1792 in the National Army Museum.

The impact of this historic understanding of British art continues, entrenching a separation between the ‘green and pleasant land’ and its colonies. The art of empire has fallen through the gap, and until recently has only figured in art historical discussions at its margins.

Artist and Empire is organised into six themed rooms. In the final room, double-themed as Out of Empire and Legacies of Empire, we find works by indigenous artists from former colonies – implying that the legacies of Empire and the processes of decolonisation are solely an ‘other’ affair that only happened ‘out there’. This despite the fact that colonisation affected of a vast number of British citizens living and working in Britain.

The art from this last room would have had a much greater impact if it had, instead, been distributed throughout the earlier rooms, where its juxtaposition with the work of imperialism would have deeply probed the issues of art and empire. It would also have spelled out the fact that British colonialism constitutes a shared history – even if lived through from opposed vantage points – and that the postcolonial negotiation of Britain’s imperial legacy cannot be ‘outsourced’ to only one of the parties concerned.

Despite all this, Artist and Empire marks a milestone in an important debate and will, one hopes, be the beginning of further conversations about the British Empire’s colonial legacy. For its attempt to tackle the skewed perception of British art that is central to its colonial legacy, Tate Britain deserves praise. An exhibition not to be missed.

Artist and Empire is currently being exhibited by Tate Britain; on will close on Sunday 10 April 2016.