OU News

News from The Open University

- Home

- UK election 2019: a choice between low-tax, individualism or generous state with unknown price tag

UK election 2019: a choice between low-tax, individualism or generous state with unknown price tag

Posted on • Society and politics

Jonquil Lowe, Senior Lecturer in Economics and Personal Finance at The Open University writes for The Conversation about the tax implications of the upcoming general election.

Brexit may be the main reason for the UK’s upcoming general election, but voters are also invited to choose between two radically different types of social system with different implications for both the taxes households pay, as well as the benefits and public services they receive.

The Conservative Party’s manifesto presents a modest £2.9 billion spending increase compared to Labour’s £82.9 billion spending programme. One approach is characterised by a smaller state, lower taxes and less welfare provision. The other by a larger state, more welfare and an increase in tax that is largely directed at business and the wealthy, though it could also cause tax rises for everyone.

Both parties are looking to business to fund a major part of their manifesto proposals. The Conservatives have cancelled a mooted cut in corporation tax. This enables it to spend slightly more, mostly on the National Health Service (NHS) and a National Skills Fund, but also to promise a cut in National Insurance.

Since 2010, the coalition and then Conservative governments have raised the threshold at which income tax starts to be paid (the personal allowance) from £6,475 (2010-11) to £12,500 (2019-20). The Conservatives claim that this has taken 5.7 million people on low incomes “out of tax altogether”. However, this is not strictly correct, because many will be low earners who have continued to pay National Insurance contributions, which start on earnings over £8,632 (in 2019-20).

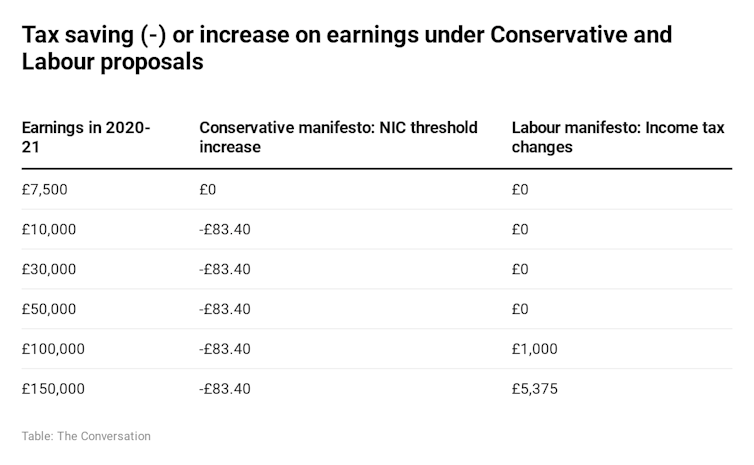

The Conservative manifesto announces an ambition – not a promise – to increase that National Insurance threshold to £12,500 as well as the personal allowance. This would save £464 per person. But the manifesto only pledges to take the first step toward this aim by raising the National Insurance threshold to £9,500 from 2020-21.

Given that, by default, the threshold would increase anyway in line with inflation, the manifesto commitment is worth about £83 a year to every employee earning above, say, £8,805 in 2020-21. Lower earners already below the threshold do not benefit.

The Labour manifesto sets out more radical and expansive reforms to welfare benefits and public services, including for example abolishing student tuition fees, free personal care for the over 65s, reforms to universal credit, increased public sector pay and higher spending on health, education and local authorities.

A large part of this would be funded through a major increase in corporation tax (with the main rate rising from its current 19% to 26% by 2023-24). But personal taxes would also rise, with the additional income tax rate (45%) kicking in from earnings of £80,000 a year rather than the current £150,000 and a new 50% rate on incomes over £125,000.

However, it is misleading to assume that the increase in corporation tax proposed by Labour would not also affect households, as the Institute for Fiscal Studies thinktank has pointed out. The nature and size of the impact depends on how companies would respond to the increase. It could be passed on to consumers in higher prices, to workers in lower wages, or shareholders in lower dividends (which would also depress share prices). It should be borne in mind that individuals are major shareholders through their pension savings.

Continue or take a leap

In 1990, Danish sociolologist, Gøsta Esping-Andersen, published an influential taxonomy of national welfare systems. He suggested there are three distinct types:

- “Liberal” regimes with a heavy reliance on work ethic and market efficiency. State benefits tend to be means-tested, minimal and sometimes stigmatised. Citizens typically pay less in tax but have to spend more personally on insurance and services or go without. Esping-Andersen pointed to the US, Canada and Australia as examples.

- “Conservative corporatist” regimes that revolve around the traditional family, with the right to welfare benefits accruing to workers who then support their dependent family. Esping-Andersen cited Austria, France, Germany and Italy as examples.

- “Social democratic” regimes which are characterised by the principle of equality, with relatively generous welfare state and public services available to all. Tax rates are typically higher but citizens have to spend less personally on the insurance and services they need. This model is most evident in Scandinavian countries, such as Sweden and Denmark.

Pure examples of these regimes are rare and, as in many countries, the UK has elements of all three. But when the electorate goes to the polls on December 12, UK citizens will be invited to vote for a marked swing towards the “social democratic” system if they vote for Labour or a continuation of a dominantly “liberal” regime if they vote Conservative.

It is an intriguing ideological choice: continue with the low-tax, small state, individualist regime that has largely characterised the UK since the Thatcher era. Or take a leap into a more “social democratic” regime with more generous and inclusive state provision but a substantial and, at this stage, largely unknown price tag.

Jonquil Lowe, Senior Lecturer in Economics and Personal Finance, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.