You are here

- Home

- Fred Hoyle’s The Black Cloud

Fred Hoyle’s The Black Cloud

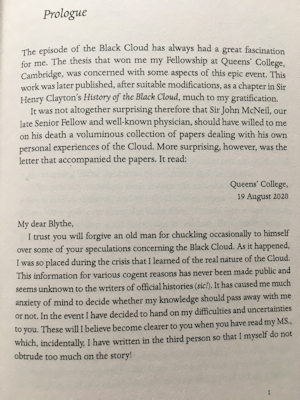

19 August 2020 is the date of the letter in the Prologue to Fred Hoyle’s first space science fiction novel, The Black Cloud, published in 1957. Born myself in 1957, I have been waiting all my life for an opportunity to write about The Black Cloud on this very date. A longer article is in preparation for the date of the note in Hoyle’s Epilogue: 17 January 2021.

19 August 2020 is the date of the letter in the Prologue to Fred Hoyle’s first space science fiction novel, The Black Cloud, published in 1957. Born myself in 1957, I have been waiting all my life for an opportunity to write about The Black Cloud on this very date. A longer article is in preparation for the date of the note in Hoyle’s Epilogue: 17 January 2021.

Fred Hoyle was a scientist of distinction. Richard Dawkins’ afterword to the Penguin edition in 1990 points out that Hoyle’s science fiction story is different to most in recognising that a superior intelligence might well not need to invade the Earth but could achieve what it wished from afar. It is also worth noting that Hoyle is prepared to accept that the alien Black Cloud is benign whereas the aliens in many science fiction stories seem to be on the side of evil.

The Black Cloud could also be seen as prophesying the climate change emergency and aspects of the coronavirus pandemic, as well as reactions to both.

First, the scientist who most resembles Hoyle says this,

‘Let’s assume that survival is possible when the Cloud gets here. Although I say survival, it’s pretty certain that the conditions won’t be pleasant. We shall either be freezing or sweltering. It’s obviously extremely unlikely that people will be able to move about in a normal way. The most we can hope for is that by staying put, by digging our caves or cellars and staying in them, we shall be able to hang on. In other words all normal travel of people from place to place will cease.’

Then, as the scale of the disaster becomes apparent to the politicians, ‘The Prime Minister was angry with the scientists’ and just wanted to know one thing:

Then, as the scale of the disaster becomes apparent to the politicians, ‘The Prime Minister was angry with the scientists’ and just wanted to know one thing:

‘First you said that the emergency might be expected to last for a month and no more. Well, the emergency has now lasted for more than a month and there is still no sign of an end. When may we expect this business to be over?’

The scientists did not know, as they had made clear repeatedly. The politicians had not been open to absorbing their message. As his closest adviser, speaking on behalf of the scientists he had come to appreciate, put it to the Prime Minister:

‘Nobody can tell you. It might … {be} a week, a month, a year, a millennium, or millions of years. Nobody knows.’

As a legal philosopher, part of my interest in the AstrobiologyOU project is wondering what, if we were to discover intelligent life elsewhere in the Universe, that might tell us about the nature of law and whether the quest, or the imagining of such life, might tell us that anyway, whether or not alien life is ever found?

Law does not appear in Hoyle’s story until late in proceedings and then is initially dismissed as no use in this emergency. A team of top scientists has been assembled in a place of secrecy in the Cotswolds, Nortonstowe, together with the Prime Minister’s private secretary, as they seek to communicate with the alien Black Cloud. No doubt Hoyle drew on his own experience in the Second World War of being drawn to lead the theoretical physics team working on radar for the Admiralty at Nutbourne.

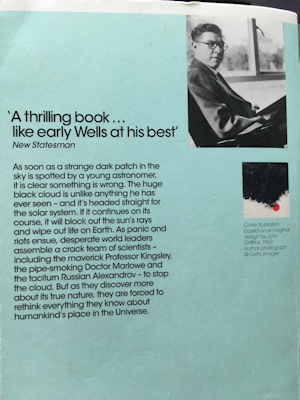

An amateur astronomer was the first to spot the cloud and then the Astronomer Royal and a Cambridge scientist, Christopher Kingsley (perhaps modelled on Fred Hoyle himself), had taken up the issue. American scientists had independently seen the cloud. Over a few months, it moves towards our Sun, tracked by the British and American governments, scientists and military commanders. The Cloud is now hovering near the Sun, causing what we might now describe as climate change on Earth.

In an echo of Bletchley Park code-breakers during the Second World War, the British team devise a code for communicating with the Cloud. Meanwhile, the US, UK and USSR authorities are taking a more confrontational approach. The Americans and Russians launch missiles at the Black Cloud. The Cotswolds team forewarn the Cloud which they call Joe, and the Cloud takes action to repel the missiles, sending them back towards their home countries. Three explode in American cities. The scientists are suspected of being in league with the alien Cloud and their lives are at risk. They might be described at this point as galactic whistleblowers. They are in the right, whereas their governments, through their military commanders, have fired without justification. At least the British scientists had the Cloud on their side. But the first communication after the rockets tells them that the Cloud is going to leave its current position near the Sun in ten days. They had thought the Cloud would stay for fifty or a hundred years. So now they are vulnerable. Francis Parkinson, the civil servant with them, says in the last chapter,

In an echo of Bletchley Park code-breakers during the Second World War, the British team devise a code for communicating with the Cloud. Meanwhile, the US, UK and USSR authorities are taking a more confrontational approach. The Americans and Russians launch missiles at the Black Cloud. The Cotswolds team forewarn the Cloud which they call Joe, and the Cloud takes action to repel the missiles, sending them back towards their home countries. Three explode in American cities. The scientists are suspected of being in league with the alien Cloud and their lives are at risk. They might be described at this point as galactic whistleblowers. They are in the right, whereas their governments, through their military commanders, have fired without justification. At least the British scientists had the Cloud on their side. But the first communication after the rockets tells them that the Cloud is going to leave its current position near the Sun in ten days. They had thought the Cloud would stay for fifty or a hundred years. So now they are vulnerable. Francis Parkinson, the civil servant with them, says in the last chapter,

‘I must say it’s a grim prospect for us now. Once the Cloud has quit we are finished. There isn’t a court of law in the world that would support us …’

This is where Parkinson is wrong, in my judgment. Some courts would have found a way to protect these heroes, relying for instance on the ancient writ of habeas corpus or the equivalent in their legal systems. Even if there were judges who would not have supported them when Hoyle wrote the novel, in the 1950s, judges would be more likely to do so nowadays.

As it happens, later in The Black Cloud, the law does seem to have provided some protection:

‘In short, Parkinson was able to persuade the British government to take no action against its own nationals and to resist deportation orders for the others. Repeated attempts at deportation were in fact made, but as national affairs stabilized themselves and as Parkinson gained increasing influence in Government circles it became progressively easier to resist them.’

Bigger questions about the nature of law, though, are prompted by The Black Cloud. This Cloud takes energy from the Sun. We might assume that it is permitted, in what I will call its legal system, to use ‘our’ Sun whereas we think that Outer Space cannot be owned by anyone. If we are not alone in the Universe, and if there is other intelligent life, their laws on discovery or colonisation or exploitation of stars or planets might reasonably differ from ours, for instance as an incentive to sharing energy. How could we then resolve disputes?

Law is about public arguments put forward on different sides of a dispute with a reasoned judgment by an independent third party whose authority is generally accepted, in pursuit of justice and usually subject to a series of appeals. What characterises law is that the Cloud and the humans at Nortonstowe could recognise and submit to the value of a fair system to adjudicate on any points of challenge or coordination for sharing the same ‘space’ in the interests of the common good, giving as much space as possible to diverse lifestyles. If we can understand that, so could a superior intelligence such as the Cloud. Not all human beings will see the value of the rule of law in extreme circumstances, as illustrated by the military and the governments firing rockets at the Cloud. In hindsight, thought, they might appreciate that law could have provided a better way forward towards our common good.

Whether or not there ever is a Black Cloud, reflecting on this helps our understanding of law in more mundane matters. The period between the dates in Hoyle’s Prologue and Epilogue turns out to encompass not only lockdown in response to the Covid-19 pandemic but also much of the 11 month transition period following the UK leaving the EU. Following this, there will be tensions between law in the legal systems of the UK and in the EU.

As for the question of our uniqueness in the Universe, the last page and a half of Dawkins’ 2010 Afterword to The Black Cloud of 1957 is reverential, almost mystical, and certainly open to the possibility that we might not be alone in the Universe. Dawkins is here even open to some superior intelligence which might be described as a god, which is especially striking as he is perhaps our planet’s best-known living atheist:

‘The last words leave us exhilarated, even stunned, as we look back at this astonishing novel: “Do we want to remain big people in a tiny world or to become a little people in a vaster world? This is the ultimate climax towards which I have directed my narrative”.’

Those last words are in the epilogue, dated 17 January 2021, which will be a good day to return to reflection on The Black Cloud, on the Law of Space, on law more generally and on whether we are alone in the Universe.

Author:

Professor Simon Lee

is Professor of Law

in the Faculty of Business and Law

at the Open University