Jenny Cattier

PhD student, Anglia Ruskin University

When I saw the conference programme for The Book as Cure: Bibliotherapy and Literary Caregiving from the First World War to the Present, I genuinely could not believe my luck. As a creative writing PhD student researching bibliotherapy, there were so many compelling paper titles it was difficult to decide which panels to attend. In fact, it was the ‘Reading and Self-improvement’ event, part of the AHRC funded ‘Reading Communities: Connecting the Past and the Present’ project (also run by The Open University) in March 2016 that inspired me to pursue both my own creative writing and this field of academic research. Since then I have been immersed in existing scholarship on bibliotherapy and have started to design my own empirical research in the area. However, as every PhD student knows too well, independent research can be isolating and lonely. There really is no substitute for a conference and the opportunity to listen to and question experts in your field. Fortunately for me The Book as Cure appeared on my radar just as I was beginning to feel the need for peer input very keenly.

Under the aegis of the Open University’s History of Books and Reading (HOBAR) research collaboration and organised by four English and Creative Writing academics at The Open University – Shafquat Towheed, Siobhan Campbell, Sara Haslam, and Edmund King – supported by plenary speakers Dr Jane Potter (Oxford Brookes University) and Dr Peter Leese (University of Copenhagen), the event marked the centenary of the war’s end and guided attendees on a bibliotherapeutic journey from wartime to the present.

Dr Potter opened the sessions by describing some of the perceptions surrounding bibliotherapy during the First World War; not only in terms of its importance to traumatised and injured soldiers, but also for those left waiting at home for loved ones. Her keynote lecture: ‘The Solace of Literature: Reading and Writing in the Great War’ noted that psychiatrists, nurses and surgeons became increasingly convinced of the therapeutic benefits of reading and quoted one wartime caregiver who observed that until this point “We protected his [the soldier’s] stomach but forgot his brains.” She also highlighted the importance placed on the hospital librarian who “understood both books and men”, a highly esteemed and respected role, that was remarked upon across several of the day’s presentations.

As was acknowledged on Twitter, a number of key themes emerged early on: we repeatedly heard the terms ‘administering’, ‘prescribing’, and ‘dispensing’ used in relation to the provision of books for their curative properties. Mary Mahoney’s research suggests that the adoption of a very scientific or medical approach to bibliotherapy was particularly prevalent in America in the 1920s and 1930s. These analogies were echoed throughout the day, with references to reading acting as medicine for the troubled mind. An excellent example of this came from the journal of the writer and scientist (and MS sufferer) W.N.P. Barbellion (1889-1919), who wrote in his journal the phrase: ‘what I do is drug my mind with print’. We heard doctors of the day cautioning on reading the ‘wrong’ kind of novels, and how the consumption of these could cause ‘overdose’ and lead to ‘hysteria’.

This leads us to the books used in bibliotherapy: there have been many differing opinions over the last two centuries about what is considered suitable reading material. Should specific books be prescribed, or avoided, based on a particular illness or condition? One wartime writer noted that ‘Jane Austen has taken her fragrant way into a surprising number of dug-outs’ which stood in contrast to the advice of some medical professionals of the time, who recommended literature that promoted ‘detachment, elevation, and mental economy’. Kipling’s ‘The Janeites’ also refers to Austen’s, perhaps unexpected, popularity with those in the trenches. On this subject, Laura Blair’s presentation: ‘Reading, Asylum Libraries, and the Asylum War Hospital Scheme’, we heard how asylums and their libraries were turned over to war hospitals and how strong concern was voiced regarding ‘appropriate’ reading material and particularly the fear of encouraging ‘addiction to novels’. Yet, from soldiers’ diaries and hospital librarians’ records we can see that reading tastes were eclectic, with detective stories, poetry and romance very much in demand.

Portrait of Rudyard Kipling from Rudyard Kipling by John Palmer. Used under Wikipedia:Text of Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License

The subject of the detective tale used in bibliotherapy was broached several times; first in George Simmer’s paper “Kipling’s ‘Fairy-Kist’: Bibliotherapy Gone Haywire?”. Simmer reviewed what may have been Kipling’s own experience of bibliotherapy, making the case that Kipling’s childhood reading of Julia Ewing influenced the writing of his only detective story, Fairy-Kist (1928), about an ex-serviceman who hears voices, and ends up the prime suspect in a murder case. Simmer suggests that Ewing was the Jacqueline Wilson of the nineteenth century, taking difficult subjects and making them accessible, this being why she would have appealed to the troubled young Kipling.

An especially emotive case study demonstrating the efficacy of bibliotherapy for children suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder came in the final session of the day from Wendy French who read a poem from an adolescent boy. His writing expressed the depths of his self-loathing by listing all the ways ‘shit’ served more purpose in life than he did. This particular boy related to Michael Morpurgo’s illustrated book Not Bad for a Bad Lad in his counselling sessions and this enabled an on-going and positive dialogue with French.

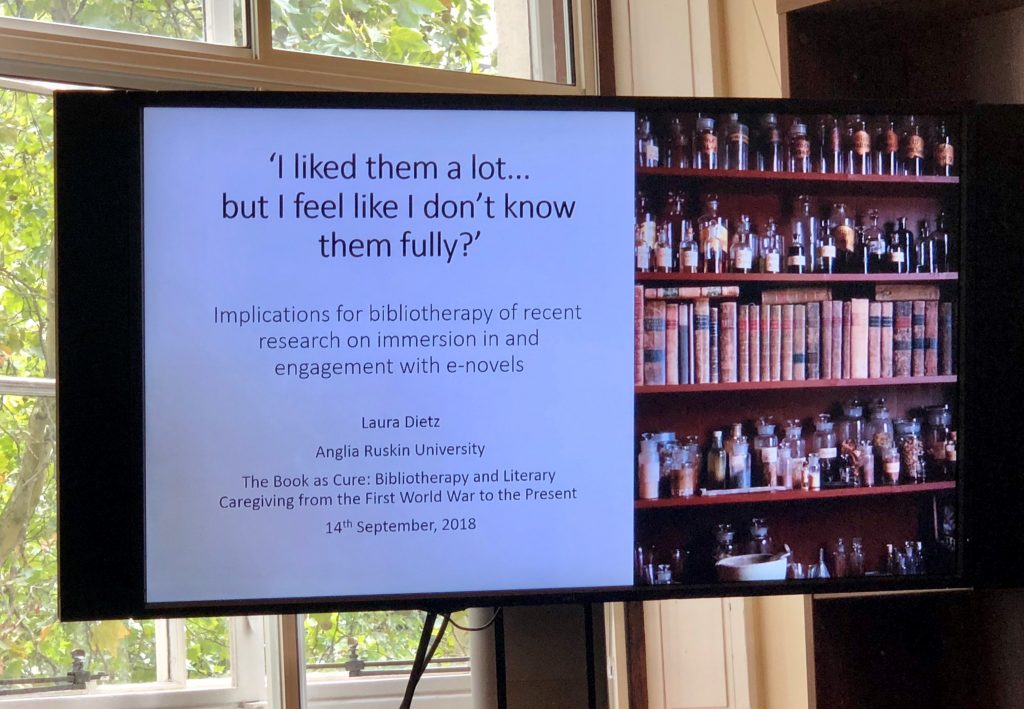

A particular highlight for me was the chance to hear in detail the important research being undertaken by Laura Dietz, my second supervisor at Anglia Ruskin University. Her work into immersion and engagement with e-novels, suggests that screen reading, on devices such as Kindles and iPads, may see the reader equally immersed in the narrative as with a printed book. For many reasons, most notably their accessibility, digital books are critical to bibliotherapeutic practice. Dietz’s research used a wider range of e-book formats compared to earlier studies, which is perhaps one of the reasons her findings reveal narrative immersion to be a more nuanced or complex phenomenon than was initially believed.

On a personal level, one of the standout aspects of conference was the friendliness and generosity of the organisers, experts and panellists. All of the presentations I attended were insightful and persuasively communicated. I am delighted to have already exchanged emails, received papers and references for further reading that will enrich my research, which explores the place of short and fantasy fiction in bibliotherapy for women with depression.

In the summary session we mused over the key questions that had arisen over the course of the day: Is reading inherently good? Does the genre of the literature make a difference? Is the term ‘bibliotherapy’ itself a valid or helpful one? What does the future hold for the field and who should be advocating and delivering bibliotherapy? Is the future digital? Is the efficacy of bibliotherapy limited to specific audiences? For each of these questions the conference provided empirical indicators, anecdotal evidence and qualitative findings, all of which deserve further, deeper, and broader exploration. I, for one, hope that there is a follow up conference for The Book as Cure and I expect this sentiment is shared by the majority of attendees.

I’ll end my account with a quote from my own paper where Alan Bennett, in William Seighert’s The Poetry Pharmacy, encapsulates the essence of a good book but also that of successful bibliotherapeutic intervention:

“The best moments in reading are when you come across something – a thought, a feeling, a way of looking at things – which you had thought special and particular to you. Now here it is, set down by someone else, a person you have never met, someone even who is long dead. And it is as if a hand has come out and taken yours.”

Jenny Cattier is a PhD researcher at Anglia Ruskin University examining the therapeutic potential of short fantasy fiction for female depression. Her thesis will be fifty percent research and critical commentary, and fifty percent of her own creative writing which will take the form of a collection of short stories.

Very interested in your research. I am doing something similar with the WEA for whom I work as an English Lit. Tutor. I have now given two papers on the subject for ESREA an international adult education forum and am planning a third for next month, focusing mainly on poetry. I sadly missed that OU course as I was away so it was great to have a summary of it. Thanks