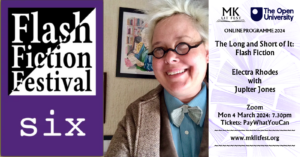

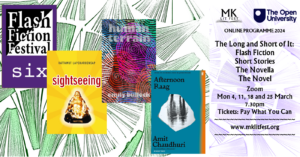

This spring our Contemporary Cultures of Writing research group is collaborating with Milton Keynes Literary Festival to run The long and short of it: From flash fiction to the doorstop novel – a series of online and in-person conversations between OU creative writing scholars and acclaimed authors. We’re kicking off the series at 7pm Monday 4 March with an online event with flash writer Electra Rhodes, who’ll be in discussion with Open University PhD student Gwyneth Jones.

To whet your appetite, Gwyneth shares here why she likes to keep things small.

Flash fiction, which tells a complete story in just a few hundred words, takes brevity as its starting point and as permission to break rules. It holds in tension the practice of narration (the art of spinning out events in an engaging way) and techniques of concision (eliminating all but the most necessary) to imply much more than is actually on the page.

I began writing flash fiction about seven years ago, fascinated by the way it can use form as content and by the way the writer enfolds meaning for the reader to discover. Flash is neither easy nor quick to write, but it does offer great freedom to experiment.

Things that might be difficult to sustain or that would become exceedingly tedious in longer form fiction can be creatively explored within the sandbox of flash. Unusual points of view for instance, unusual tenses (future conditional, perhaps?), or alphabet games. Some inspiration for this comes from the Oulipo Group who impose strange external restrictions to gain writerly freedom – Oulipians are said to be ‘like rats building a labyrinth from which they plan to escape’. These are some of my labyrinths.

Things that might be difficult to sustain or that would become exceedingly tedious in longer form fiction can be creatively explored within the sandbox of flash. Unusual points of view for instance, unusual tenses (future conditional, perhaps?), or alphabet games. Some inspiration for this comes from the Oulipo Group who impose strange external restrictions to gain writerly freedom – Oulipians are said to be ‘like rats building a labyrinth from which they plan to escape’. These are some of my labyrinths.

Unusual Point of View

Writing in second person can be slightly disconcerting for the reader who is asked to identify with the ‘you’ of the narrative. This is an excerpt from my flash fiction ‘Not Lost or Drowned’ published in Life on the Margins, about a woman escaping from a toxic relationship.

You’re staying alone in a caravan. You walk to pass the time. Sometimes you take the bus into town, cruising past trinket shops. You see missing posters, signs of desperation, fly-posted along the coast. She has, or had, the same name as you. Unsettling to see it there above a number to call, day or night. You memorise it, test yourself at the next poster, and the next, till you know it by heart.

Fibonacci Sequences

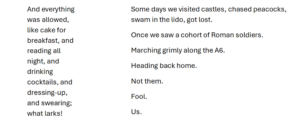

That is, writing in sentence lengths that correspond to the Fibonacci sequence where the last two numbers are added together to make the next (e.g. 1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21, etc). The rigidity of form compels the writer to add and/or subtract words with potentially unexpected results. I wrote ‘Aint no Cure for my Fibonacci Blues’ (published in The Real Jazz Baby) inspired by summer holidays with my slightly batty aunt. It opens with two one-word sentences and builds up to a fifty-five-word sentence and then back down. This is the ending:

Lipograms

The Oulipo group often devised lipograms – omitting one or more letters of the alphabet. The letter e, of course, is the hardest. I tried this in ‘No e in Pornography’ about a man whose ‘browsing history rats him out’ which was published online by Reflex Flash. I think the lack of e gives the writing a spikey brittle quality.

Not so sorry, thinks Nina, for abnormal cravings. Not sorry to bring havoc to Nina’s world. In outwardly lax administrations, such things flourish with abandon. Sonny looks long at icons of dissipation; nothing is off limits to a thin bald man with roving digits.

Breathless Paragraph

A form quite common in flash fiction is ‘the breathless paragraph’, that is, maybe three or four hundred words, written as one continuous sentence. This can result in a soaring arc of narrative or a relentless sense of inevitability. ‘Exegesis’ was published in the anthology In Defence of Pseudoscience

They’ll say she was asking for it, look at her, in her cheap skirt, scuffed heels, bitten nails and it’s obvious how she started out, a skinny, snot-nosed kid off the estate, no pony rides or chocolate eclairs for her, no, it was all ‘never mind your homework, mind your brothers,’ coz her mother was on tablets for her nerves, and what can you expect, absent father, feckless mother, things like that make a girl grow up fast, start using what she’s got to get where she wants, but as the saying goes, fruit doesn’t fall far …

Some other examples of experimental flash fiction from some brilliant writers:

- Hermit Crab, taking a ‘readymade’ form such as a recipe, or lonely-hearts ad and telling the story within that form. Tim Craig’s ‘That’s All There Is, There Ain’t No More’ uses cribbage instructions.

- Conceit or extended metaphor such as ‘Unbinding’ by Kathryn Aldridge-Morris which begins ‘My mother was a First Edition Pelican original’.

- Inventory, using a list to tell the story such as ‘LifeColour Indoor Latex Paints – Whites and Reds’ by Kristen Ploetz.

The experimentation and playfulness of flash fiction is a big part of its appeal for me. Sometimes the constraint of the experiment – ‘the labyrinth’ – will be evident in the finished work. At other times, it is nothing more than an escape hatch or a catalyst to spur creativity.

Gwyneth Jones is a writer of short and flash fictions under the pen name Jupiter Jones, and her work has been widely anthologised. She is also the author of three novellas-in-flash, the most recent, Gull Shit Alley and Other Roads to Hell was shortlisted for the Saboteur Award. She is currently a PhD candidate at the Open University researching (dis)connectivity in the novella-in-flash. Her supervisors are Dr Emma Claire Sweeney and Dr Jane Yeh.

Go to MK Lit Fest’s website to book your free ticket for Gwyneth Jones’ online event with acclaimed flash fiction writer Electra Rhodes