Shafquat Towheed, Senior Lecturer in English

Hilary Mantel has been lauded for reviving the fortunes of the historical novel in English, for being the first woman writer to have won the Booker Prize twice (2009, 2012), and for selling over five million copies of her books – but where did it all start? Where did Mantel become a writer, hone her craft, and enter the public domain as a published novelist? What were the social and environmental circumstances that facilitated her arrival as an author?

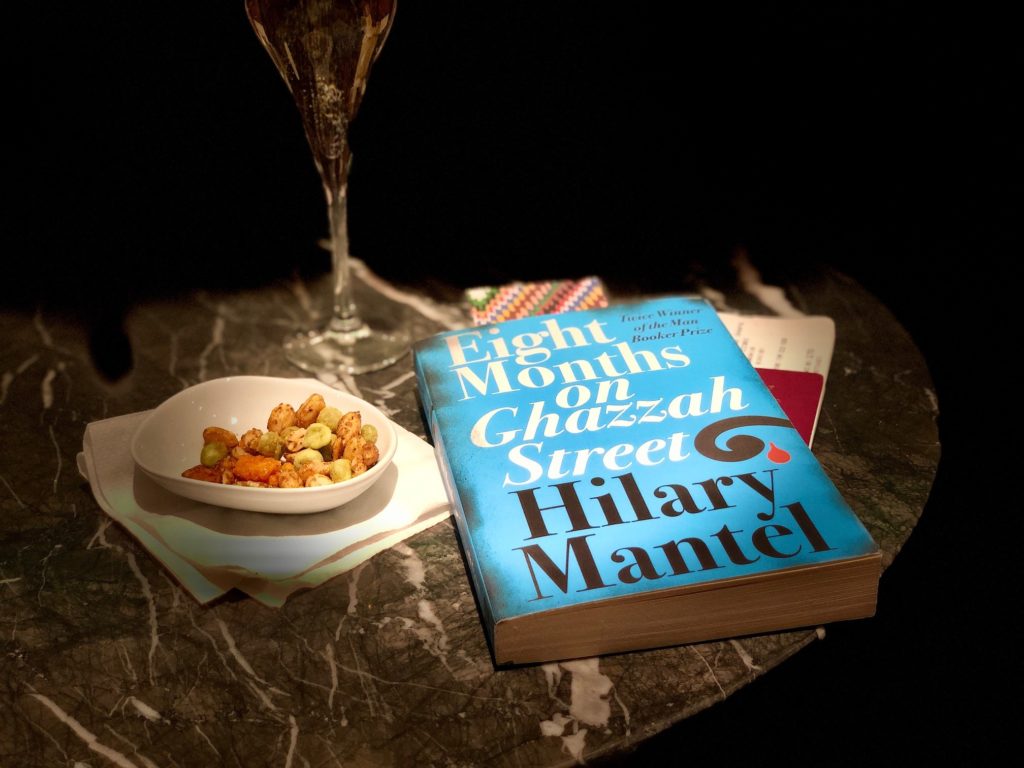

I had recently been reading Mantel’s third novel, Eight Months on Ghazzah Street (London: Viking, 1988), which is set in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in 1984-85, and tells the story of Frances Shore, the unhappily married cartographer wife of a civil engineer on an expatriate work contract in the Kingdom. The novel is perhaps the best evocation of 1980s Saudi Arabia written by a woman in English, and carefully reconstructs the oppressive, punitive environment that she encounters. A mapmaker stranded in a city without signs, Frances Shore observes that pavements in Jeddah exist to stop cars crashing into buildings, and not for the benefit of pedestrians. Her large apartment on Ghazzah Street has windows with views of blank compound walls, and she can only glimpse a view of the sea by climbing to the roof. Denied the opportunity to work or drive, Frances Shore reads her way through all the detective novels she can find, while keeping a diary of her claustrophobic life and trying to reconstruct the lives of others around her. It is a compellingly atmospheric novel.

When I recently went to Saudi Arabia for a short visit, I had to go and find Ghazzah Street, and see the place that Mantel had reimagined in her fiction for myself. Within 72 hours of setting foot in the Kingdom, I was there, and a spot of surreptitious literary detective work (and pilgrimage) had begun.

So here is Ghazzah Street, 9 blocks in from the sea, in Hamrah in Jeddah’s downtown, just off Shari’eh Falasteen (Palestine Street). Several of the buildings look plausible as the likely home of Frances Shore in the novel -which thinly fictionalised the first apartment Mantel actually lived in. Much has changed – Ghazzah Street now has a swanky business hotel, Palestine Street is beautifully pedestrianised, and women are allowed to drive – but parts of the built environment dating from the 1970s and 1980s are exactly as Mantel would have encountered and thinly fictionalised in the novel. In fact, Mantel spent not eight months in Jeddah, but stuck it out for four years, in three different addresses in Jeddah and one outside of the city, accompanying her geologist husband.

Mantel hated her time in Saudi Arabia and to the best of my knowledge, has never been back. And yet, it was those four years, living in the most gender repressive society on earth, that was the crucible that forged her as a writer. She had time to write, as denied the ability to work or drive, she could do little else. Like her fictional character Frances Shore, Mantel read her way through the British Council Library’s collection of detective fiction, and similarly, kept a diary of her day to day life. She arrived as a housewife and left as a professional writer, with two novels under her belt, and the material – her Jeddah diaries – for her third, Eight Months on Ghazzah Street, ready to go. She worked through her material and wrote the novel back home in England during the winter of 1986, in a world that ‘always seemed to be dark’. Even before the novel was published, Mantel’s Jeddah material was winning awards: her first literary prize was as the first ever recipient of the Shiva Naipaul Memorial Prize for Travel Writing (1987) for a piece on Jeddah.

So, if you are thinking of the place that turned Hilary Mantel from a geologist’s wife into an award–winning novelist, look to Jeddah, and not just for the inspiration for Eight Months on Ghazzah Street. Surely, there could have been no better preparation for writing about absolute male patriarchy and the divine right of kings in Tudor England than having lived in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia? Perhaps even more ironically, Mantel now has a readership within the Kingdom: Wolf Hall and Bring up the Bodies are both openly sold and read there, as my own visit to Jarir Books, Jeddah’s largest physical and online book retailer, located just a few kilometres away from Ghazzah Street, proved.