Patricia Ferguson, PhD student, English Literature

I have taken as my title this arresting phrase with which the poet Matt Kirkham, writing in ‘The Belfast Agreement: Twentieth Anniversary Issue’ of Irish Pages, sums up the Good Friday Agreement, an anniversary which is also the theme of this year’s Imagine! Festival.[1] In his preface to the programme, the director Peter O’Neill invites us to enjoy ‘a unique way of imagining the future of this great city [ … ] as we try to make sense of this volatile world’. It builds on last year’s theme of restorative justice, which asked, ‘How do you change a punitive mindset into a restorative one?’

On that occasion I learned about friendship clubs, integrated schools, and heard Loyalist and Republican ex-prisoners speak from the same platform. I thought this last the most heartening of all. I thought that this Irish genius for conversation, which they call the craic, might prove sufficient to heal the city’s wounds. I realise now that none of last year’s conversations could suffice, because not one of them was impossible, not even that between the ex-prisoners. That conversation, I now see, was not in fact between them; they told their stories to us, the audience, not to each other, and left the stage unreconciled.

The conflict lasted so long that ‘only people of my age, pensioners, can recall what the peace was before the Ulster Troubles. We can speculate what life might have been like, had we not had our thirty year war’.[2] Given such a history, that the Agreement ever happened is something of a miracle, but the brittle accord which it achieved might yet be shattered by Brexit into nothing more than a twenty year truce, because, as Mary Robinson warned, it institutionalized sectarianism. Can there be any irony more bitter than this, that ‘when a cross-party delegation visited South Africa, even Nelson Mandela had to address Unionists and Republicans separately’?[3] If the peace is to survive, let alone grow stronger, they must learn to talk to each other.

The poet Damian Gorman (‘What Rhymes with Conflict?’), who spent ten years working with young people from both sides of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, understands this perfectly. He read to us from his poem ‘If I was us, I wouldn’t start from here’, which is a reflection on the Agreement. He exhorted us to ‘tell your story until it’s told’, but no less vitally, to listen to the other person’s story – and he means listen; to do that, he said, you must clear a space inside yourself and let your enemy in, because ‘Each generation has a sacred task – |To tell a better story than it was told’.

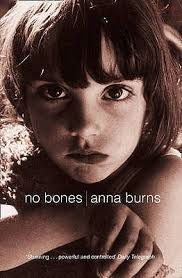

I helped facilitate the Open University’s event, ‘Reading in Conflict’. The members of my group got no further than the first extract, a passage from Anna Burns’s novel, No Bones, set in Belfast in 1983, and bringing back the most searing memories of growing up as children of the Troubles. I wish I could have recorded their stories! But as with the ex-prisoners, Catholic and Protestant talked to us, the visitors, not to each other. As the week went on I became ever more aware of the Belfast people’s urgent need to find ways of talking to each other across the sectarian divide – but how can they, when the very geography of the city is designed to stop them? The Peace Walls are obvious enough, but a multi-disciplinary research project at Ulster University, (‘Hidden Barriers’) has been able to prove that, in redeveloping the city, the authorities closed off former thoroughfares, divided through-streets into cul-de-sacs, and put in ‘a proliferation of dead-end alleyways and courtyards with a single entry-exit point’ with the express purpose of keeping Catholic and Protestant apart, a policy which defines Belfast to this day.[4], [5]

I helped facilitate the Open University’s event, ‘Reading in Conflict’. The members of my group got no further than the first extract, a passage from Anna Burns’s novel, No Bones, set in Belfast in 1983, and bringing back the most searing memories of growing up as children of the Troubles. I wish I could have recorded their stories! But as with the ex-prisoners, Catholic and Protestant talked to us, the visitors, not to each other. As the week went on I became ever more aware of the Belfast people’s urgent need to find ways of talking to each other across the sectarian divide – but how can they, when the very geography of the city is designed to stop them? The Peace Walls are obvious enough, but a multi-disciplinary research project at Ulster University, (‘Hidden Barriers’) has been able to prove that, in redeveloping the city, the authorities closed off former thoroughfares, divided through-streets into cul-de-sacs, and put in ‘a proliferation of dead-end alleyways and courtyards with a single entry-exit point’ with the express purpose of keeping Catholic and Protestant apart, a policy which defines Belfast to this day.[4], [5]

We saw some of this for ourselves, looking at Ligoniel through virtual reality headsets, and then properly on the ‘History of Terror Walking Tour’. Like Damian Gorman, our guide Paul Donnelly has spent years as a mediator; ever since the ceasefire he has been working on dialogue projects between Loyalist and Republican ex-prisoners. The interview he gave to Chris Luecke for ‘Pubcast Worldwide’ can be found here It’s well worth a listen!

Perhaps it is because of the Brexit frenzy that the divide seems deeper than ever this year. When on the one hand I heard the poet Pádraig Ó Tuama of the Corrymeela Community use a story from the Bible (‘The Book of Ruth, the Moabites and Brexit’) to illustrate his plea for generosity and a more civic discourse; then on the other heard Ruth Dudley Edwards, quoting her friend Lionel Shriver, dismiss Sinn Féin as a ‘cancer’ (‘How Violent Republicanism Entrenched Partition’), I think I was the only person who had attended both talks. The question and answer sessions made it quite clear that neither group was there to learn; they were there to be comforted in the views they held already. Here are a few more lines from Damian Gorman’s poem on the Agreement:

The kind of myth my generation supped

Was, ‘We have better heroes than they’ve got.

For ours are much more decent – to a fault,

And if we’ve a rotten apple, they’ve the Rot’.

I burn to point out which side it is that has the Rot, but I know that until I can be cured of that, I am not part of the solution but part of the problem. I too must learn, in the poet Moya Cannon’s delightful phrase, ‘the nobility of compromise’.[6]

[1] ‘Mission Impossible’, Irish Pages, 10, no. 2 (2019), 148-60 (p. 159)

[2] Robert McDowell, ‘On Educating Memory’, ibid. 138-40 (p. 119)

[3] John Gray, ‘A November Night’, ibid. 61-68 (p. 64)

[4] David Coyles, Brandon Hamber and Adrian Grant, Hidden Barriers and Divisive Architecture: The Case of Belfast (Belfast: Ulster University, 2018), p. 10

[5] To this day, indeed: a headline in the Belfast Telegraph, 9 April 2019, reads: ‘It should be renamed Sectarian Street – [Orange] Order questions building of houses near Belfast Orange Hall’.

[6] Title of Moya Cannon’s article, ‘On the Nobility of Compromise’, Irish Pages, 10, no. 2 (2019), 76-83

Beautifully written and sensitive piece.

Really good piece, Patricia – when walls are physical as well as metaphorical/emotional/spiritual, how does one move forward? Thank you for your honesty in your reflections too.

Many thanks Patricia, for such a thoughtful and considered reflection on this year’s Imagine! Belfast festival. I think you’ve captured some of the charged (even at times, frantic) atmosphere in Belfast in what might have been Brexit week. I’m also really interested by how divisive the Anna Burns ‘No Bones’ extract proved to be this year – people on my table again either loved it or hated it, and brought to bear their own personal experiences of living in Belfast in the early 1980s as evidence to support (or demolish) the novel. Quite an amazing lightning rod, I think, to get participants to think about memory, fiction, lived experience, and the relationship between them. Thanks again!