Dean de la Motte’s name will be familiar to anyone who attended our February 2019 Contemporary Cultures of Writing event, ‘The lives of others: research and writing’. The panel’s chair, OU Senior Lecturer Fiona Doloughan, suggested that both Dean and his fellow speaker might be breaking out of their comfort zones by applying their intellectual and emotional energy to new genres. Fiona Sampson was turning from poetry to biography, while Dean was moving from literary criticism to the writing of fiction.

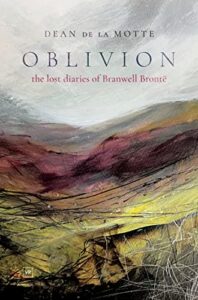

Now that Dean’s novel Oblivion: The Lost Diaries of Branwell Brontë has been published by Valley Press, Fiona D. catches up with him again to discuss why he made the transition from authoring academic to creative works, and what he has learnt in the process.

Fiona: Congratulations on the publication of your novel. Tell us about your long-standing interest in the Brontës, and how you came to be particularly interested in the sisters’ lesser known brother, Branwell.

Dean: I read the Brontës in school, though I confess that I was not any more interested in them than I was in Dickens or Eliot, and arguably less so than in Hardy, whom I still love. In the mid-1990s I was designing a course called ‘Writing the Nineteenth Century’, where I paired works of fiction with works of history, including Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley and a book on the Luddite rebellion. I read Juliet Barker’s magisterial The Brontës and learned for the first time the full story of the family, including how Branwell fit into the family dynamic.

I was utterly fascinated with him, perhaps because I could (at least in remembering my 20-something self) relate to him, if not to his actions at least to his character traits and flaws.

I conceived the idea of a novel called Oblivion, inspired by a) the oblivion into which he and his works have fallen; b) his own attempts to drink (and perhaps drug) himself into oblivion; c) the recurrent theme of a desire for oblivion (the word appears often in his poetry) or escape from the sorrows of existence, and d) his famous portrait of his sisters, where he painted himself out, or ‘into oblivion’. I wanted the book to be something of a tribute to the style, structure and themes of his sisters’ works, though I didn’t yet know that the book would take the form of a first-person diary.

Fiona: As an academic who specialized in 19th-century literature in France and England, in some ways your interest in the Brontës is consistent with your research expertise. But why did you decide to write a novel, rather than, say, a more conventional academic monograph?

Dean: I must confess that like Branwell, I once had a burning desire to be known primarily as an author of creative works. Unlike the Brontë siblings, however, I had available the more ‘practical’ path of an academic career. I often think all of the Brontës, including Branwell, might well have become professors had they lived a century or more later! In addition, I really am a scholar of nineteenth-century France, though I have written one article on teaching Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights.

Oblivion arose from a never thoroughly defeated desire to write a novel, my fascination with Branwell (including his similarities of character to me, which allowed me a ‘safe’ sort of confessional or therapy space), and my love of the language and historical period of the Brontës.

I went into academic administration for nearly 15 years and shelved the project, but never stopped thinking about it or reading works by and about the Brontës. When I moved back to full-time teaching in 2014, I at last had the time (a sabbatical plus subsequent summers) to write the historically detailed (and long) novel you now have before you.

Fiona: One of the original impetuses behind the development of Creative Writing in the US had to do with sharpening and sensitising the critical faculties of academics and giving them the opportunity to understand ‘from the inside’ what goes into the making of a piece of literature. Did writing a novel allow you to put aside your critical faculties and venture into more creative terrain in a way that writing a monograph might not?

Dean: The process has given me enormous empathy for all those who attempt to write and publish creative works. It is hard and emotionally exhausting work, especially if, as was my case, you are drawing on your own psychic life (which I think writers nearly always do, by the way).

I have, since finishing the book, been able to use my insights and discoveries in my teaching, notably to address the construction of characters and narratives generally, and the works of the Brontë sisters in particular. I don’t think writing a biography or study of Branwell’s poetry would have provided the level of awareness I have gained from writing Oblivion.

In addition, I’m not terribly interested in or impressed by Branwell’s body of work; rather, it was his life juxtaposed with the lives and works of his sisters, and the period in which they lived, that fascinated me.

Fiona: Publishing and promoting your book this year was the culmination of years of writing, drafting, reworking and editing. Can you say more about how you succeeded in obtaining a publisher? And what did it feel felt like to engage directly with readers ?

Dean: I was fortunate to find a small independent publisher, Valley Press, located in Scarborough, a stone’s throw from where Anne and Branwell worked, and where Anne died and is buried. They do beautiful work and allowed me to publish the book – which, at 250,000 words, is admittedly very long – as I had envisioned it. I’m not convinced one of the large multinational corporations would have permitted it. In many cases, readers are great fans of the Brontës, so I am already among kindred spirits. The feedback I’ve gotten from people who’ve read the novel has been enormously gratifying, because I seem to have accomplished what I set out to do.

Fiona: Do you have plans to write another novel? If so, would it be rooted in 19th-century British culture or might you turn to a different part of the world? I know you’ve been working on Victor Hugo of late.

Dean: I don’t yet know, but I’ve got several ideas. One involves a Frenchman who sails to my native California in the 19th century, only returning to France at the end of the century. I continue to be fascinated by the enormous upheavals and transformations in France during the period 1830-1870 , as well as the ‘long 19th century’ of 1789-1914.

Dean de la Motte was born and raised in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and studied English, French, and comparative literature at UC Santa Barbara, UNC Chapel Hill, and the University of Poitiers. He has published articles and books on 19th-century French literature and culture, as well as numerous essays on the teaching of literature, including Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. The father of two grown children, de la Motte lives in Newport, Rhode Island, and spends most summers in France. Oblivion: The Lost Diaries of Branwell Brontë (Valley Press, 2022) is his first novel.

Fiona Doloughan is a Senior Lecturer in English (Literature and Creative Writing) and Qualifications’ Lead for English at the OU. She has a dual background in Comparative Literature (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) and Applied Linguistics (University of Reading). While her research focusses on contemporary narrative forms in literature, she is also interested in translation and creativity. She has published two monographs (Continuum, 2011; Bloomsbury, 2016) with a third, entitled Radical Realism, Autofictional Narratives and the Reinvention of the Novel, due to be published by Anthem Press in February 2023.