By Isabelle Parsons, PhD student, English Literature (1)

It’s a Monday morning in June and I’m standing in front of the imposing granite and marble cube that is the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. I’ve spent the past four years studying published texts, correspondence, biographies and scholarship relating to Edith Wharton’s work, especially her portrayals of women through the use of secrets and silences. Now I’m about to examine the most relevant portions of the archival paper trail of her life.

3 June – Heaven under surveillance

Inside the Beinecke cream-coloured carpet muffles sound, black leather-backed chairs surround generous desks, and Gertrude Stein looks down from the wall.

The manuscript for The Age of Innocence is being scanned off-site, so I move straight on to A Backward Glance. I note Wharton inserting the phrase ‘secret lisp’ to describe the sound of arbutus buds in the spring woods near Mamaroneck.[2] Then she adds the word ‘secret’ to describe her reading practice as ‘a secret ecstasy of communion’, before explaining why she’s chosen this particular adjective.[3] Understanding dawns – Wharton is saying that she attaches value to concealment, in an autobiography that is noticeably reticent.

4 June – Hunting for silences in The Reef

Sophy’s manifesto-like exclamation, ‘“I wanted it––I chose it. He was good to me––no one ever was so good!’”, where every pause drives home her certainty, is absent from the manuscript.[4] And the narrative leaps from Anna learning about Darrow and Sophy’s past, to a chapter I don’t recognise from the published text, one where she wakes up ‘an hour or two before dawn, got up and threw open the shutters of the bedroom windows. The intense silence of a muffled sky hung in the woods and fields.’[5] This, then, is transmission history in action, showing me Wharton’s creative mind at work.

5 June – Wharton writes women

Lawyer Royall says something extraordinary in the manuscript of Summer, omitted from the final text: “Every thing I’ve done in my life’s been a failure,” he broke out suddenly –– “and now I’ve made a failure of this too.”’[6] The next folder I open includes the view of The Literary Supplement of the London Times (1917), which finds that Royall and his ward

[…] are remarkable beings indeed, a bitter girl and a tarnished old man; […] he is a really rich piece of creation, a masterful louche, obscurely battered and defeated derelict of his world; he does not, one feels, get all the display he should have had.[7]

But the evolution from manuscript to published text makes clear that this story is not about Royall. Wharton wants us to empathise with the girl!

6–7 June – Wharton’s war

Request scan of Wharton’s talk to American soldiers – in Paris? – despite pages missing from document. Her warmth & Francophilia unmistakeable.

Judging by Roosevelt’s letters, he and Wharton egged each other on over American neutrality. Conrad’s letters unexpectedly gentle; it is 1 October 1917 and his son has just visited from the front. Then Bo Rhinelander’s excitement over getting into the thick of things with his ‘D H 4 with a 420 h.p. Liberty Motor’, envy of the English pilots, is palpable in a September 1918 letter to his mother, Wharton’s cousin by marriage.[8]

The last is a difficult read. Within weeks Bo’s plane is shot down, and Wharton calls on her impressive network to determine his fate.10 June – Secrets revealed

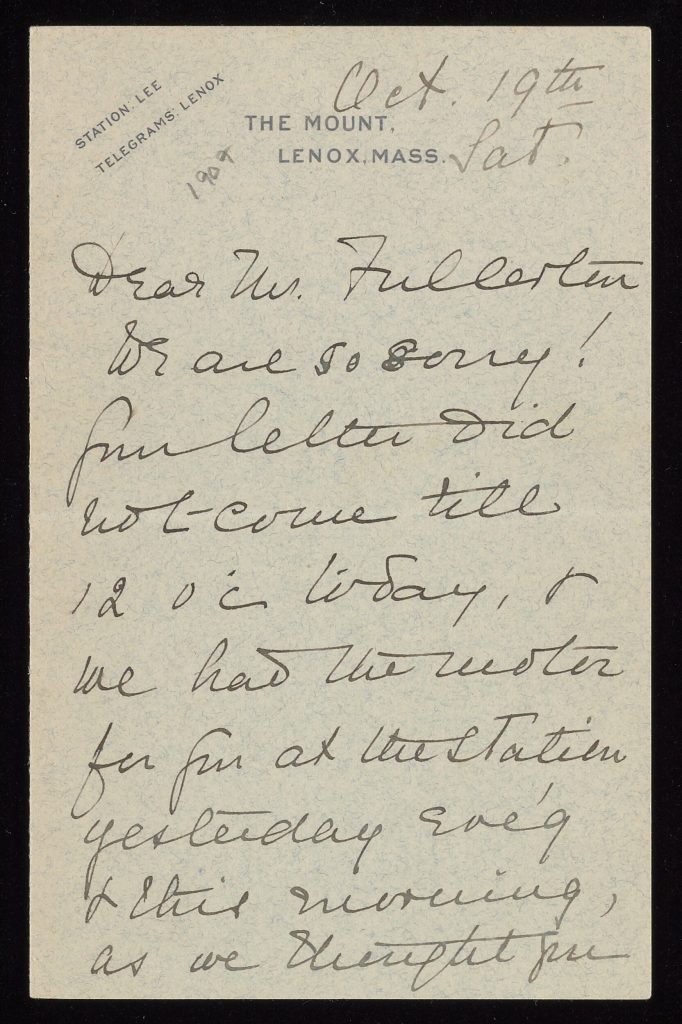

Unexpectedly discomfited by Morton Fullerton’s clandestine transcription of ‘Terminus’. Wharton destroyed the original, yet I have in front of me her intimate thoughts about a love affair that delighted and then agonised her.

Delve into Henry James’ letters, but his handwriting defies me. Call it a day and get soaked on the way home. Sandals squelching, inspiration strikes; look for Powers’ volume of James-Wharton correspondence on Internet Archive to work out which of James’ letters are not published, and focus on those!

11–12 June – The Wharton marriage

Acrimony of the Wharton separation emerges. In December 1912 she writes to Gaillard Lapsley, ‘I’ve been going through bad times. Teddy [Edward Wharton] is in London, in the clutches of a woman, + I can do nothing. Try not to see him, please. He is pursuing all my friends.’[10] Sixteen months later Lapsley hears, ‘[…] I “get my decree” in another four or five days. I find that Teddy has registered all his various temporary brides as “Mrs Wharton” in the hotels they frequented –– rather a gratuitous last touch of ill-breeding.’[11]

Then it’s early 1914; Wharton sends Lapsley postcards from North Africa containing what can only be described as toilet humour. Stifle my laughter with enormous effort. At the next desk scholars sombrely examine medieval manuscripts.

13 June – Paper trail of a life

Wharton’s 1920 diary tracks Age of Innocence’s relentless progress, and shows Walter Berry moonlighting as her New York courier, hand delivering to Appleton the novel’s completed chapters as sent to him.

Swallowing hard again, now over diary entries for Berry’s death, and maids Elise and Gross’s.

14 June – Time passes

Photograph 1938 letter from Yale president Charles Seymour to Lapsley regarding gift of Wharton’s papers. Confirms willingness to provide ‘careful housing and protection’, ‘that the correspondence and biographical material will not be accessible for a period of years, roughly corresponding to a generation’, and that Wharton’s manuscripts ‘will be accessible only to bona fide students of literature and that none of the unpublished material be published until the copyright expires’. He agrees also to ‘the necessity of guarding against the danger that the material might fall into incompetent or unwise hands in the meantime’.[12]

Notes

1. Isabelle Parsons is an Associate Lecturer and doctoral student in English at The Open University. Her visit to the Beinecke Library in June 2019 was funded through an Edith Wharton Society Award for Archival Research and The Open University’s PRA and RESSF schemes.

2. Beinecke Rare Book

and Manuscript Library, Yale University, YCAL MSS 42, Series I, Box 2,

Folder 27.

3. Beinecke Rare Book

and Manuscript Library, Yale University, YCAL MSS 42, Series I, Box 2,

Folder 28.

4. Edith Wharton, The Reef (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), p.263.

5. Beinecke Rare Book

and Manuscript Library, Yale University, YCAL MSS 42, Series I, Box 11,

Folder 320.

6. Beinecke Rare Book

and Manuscript Library, Yale University, YCAL MSS 42, Series I, Box 12,

Folder 362.

7. Beinecke Rare Book

and Manuscript Library, Yale University, YCAL MSS 42, Series I, Box 12,

Folder 363.

8. Beinecke Rare Book

and Manuscript Library, Yale University, YCAL MSS 42, Series II, Box 30,

Folder 916.

9. James W.D. Seymour, Memorial volume of the American Field Service in France: “Friends of France” 1914-1917 (Boston: American Air Service, 1921), n.p.

10. Beinecke Rare Book

and Manuscript Library, Yale University, YCAL MSS 42, Series VII, Box 59,

Folder 1706.

11. Beinecke Rare Book

and Manuscript Library, Yale University, YCAL MSS 42, Series VII, Box 59,

Folder 1707.

12. Beinecke Rare Book

and Manuscript Library, Yale University, YCAL MSS 42, Series XI, Box 65,

Folder 1795.

13. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, YCAK MSS 42, Series II, Box 25, Folder 774.

Many thanks Isabelle, for sharing these insightful reflections on your recent archival visit to the Beinecke at Yale. I think you have hit the nail on the head: for an author specific research project such as yours, there really is no substitute for spending time handling, sifting and closely examining the materials contents of the archive in situ. For all that digitisation can do for us (and it’s a great deal), the material archive calls out for close reading, deep thinking, and time for reflection, and more than anything else, it humanises the subject of research. Like you, I’ve found reading some of Wharton’s personal correspondence in the original, handwritten letters deeply (and unexpectedly) moving, showing as it does, an emotional vulnerability that is elsewhere so carefully and professionally shielded from scrutiny. I have to admit, it is the unexpected, serendipitous encounter in archives that I always find the most appealing, and I see that you had several such encounters during your research trip. I can never forget stumbling upon (and laughing) over the more humorous examples of fan mail sent to Wharton by her readers, and kept (uncatalogued) in one of the miscellaneous folders in YCAL MSS 42.

Thanks again for sharing this with us – and hope the discoveries continue in future trips to Wharton archives and special collections!