Sara Haslam, Senior Lecturer in English

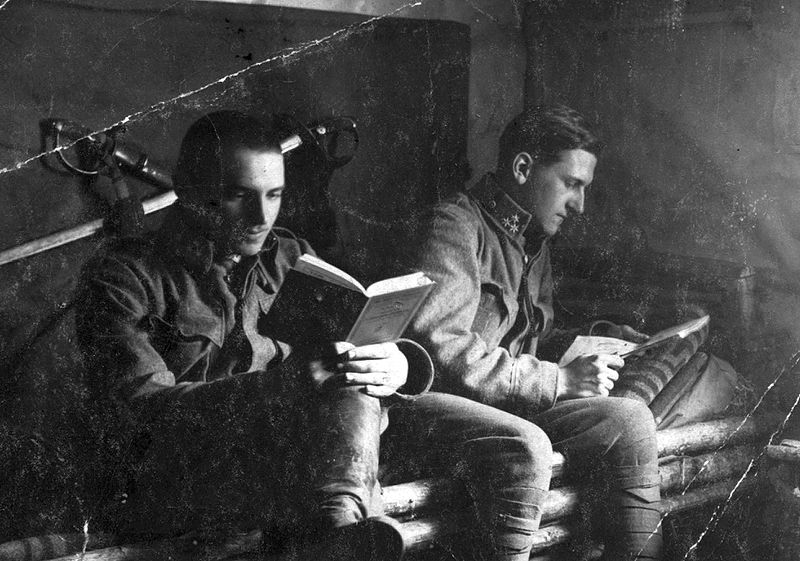

Soldiers reading during the First World War. Shared under the Creative Commons licence. Date:1917 Source http://www.fortepan.hu/_photo/download/fortepan_16325.jpg

We’ve been asking the first question in my title for this blog post for many years in our department. In modules such as A300 Twentieth-Century Literature: Texts and Debates our teaching materials have explored the relationships between art and politics, for example, and asked students to do the same. (My writing on Chekhov, the literary doctor, for A300 was perhaps an early sign of current interests.)

Recent research projects, though, have provided a new set of answers to both questions above, and reflecting on those answers for this post has proved a welcome activity.

Starting to read a thin and battered pamphlet in the spring of 2015 in Oxford’s Weston Library I had one of those ‘aha’ moments the researcher craves. I’d ordered it up because of a couple of key words in the title. Previous searches hadn’t unearthed it and I wasn’t sure until it was in front of me that it was going to be of much interest. But Helen Mary Gaskell’s account of the beginnings of her War Library in 1914 proved a wonderful find. Her epigraph, ‘Take choice of all my Library, and so beguile thy sorrow’ (from Titus Andronicus) had key words of its own, and what followed opened up the history, and challenged the scholarship, of reading during the First World War, particularly that of sick and wounded soldiers. It prompted me to find a name for one kind of organised charitable endeavour in war-time: ‘literary caregiving’ – a phrase I used in the key-note I was writing in 2015 and the article on Gaskell’s war library I’ve published since.

Gaskell’s idea for a library for sick and wounded soldiers, to be stocked in the main by donated books, was realised in the first weeks of the war. She had powerful and wealthy friends – one, Lady Battersea, had a mansion going spare in Marble Arch, which is where they stored the books. Aside from the speed with which the War Library was operational, the most striking aspect of the early weeks was the number of donations. One individual contributed a library of 35,000 books. Gaskell needed them all, and more too; supply rarely met demand. And yet records show that in the first half of 1917, for example, 1,125, 840 units were sent from the library’s London base to its depots around the world.

Gaskell also had a methodology – one related to her epigraph and to a democratised rather than hierarchical understanding of literature and its purpose. She prioritised what she called a ‘personal touch’, meaning that specific requests from wounded soldiers should be met if at all possible. Books, she felt, were a ‘flow of comfort’ that should not be interrupted by lack of effort. Over the course of the war, the War Library collected and distributed millions of books by writers such as O’Henry, Kipling, Marie Correlli, Dumas, Nat Gould – but if a soldier wanted a book on bee keeping, for example, every effort would be made to source that too.

This pamphlet was fascinating in its own terms. It also offered important answers to the question of what literature is for. And these answers, and the research directions they instigated have led to new networks and collaborations with colleagues departmentally, and externally too – a particularly positive outcome when we spend so much of our research time on solitary labours. Some of the results will be discussed in other posts here.

The tone and character of the book-related language used by soldiers and the volunteer librarians caring for them during the war will stay with me. Contemporary experience of a ‘book hunger’, of ‘the bitter cry for books’ led to the idea of books that might ‘heal’ – one that is explored in all kinds of ways in the papers those librarians left behind. The media, too, was fascinated by this work, which shifted the medical focus to include minds as well as bodies.

The Times, for example, told people ‘What to Read to the Wounded’ in 1915. It turns out, though, that both the wounded, and Gaskell and her colleagues, had other ideas. If one of the things that literature is for is healing, these caregivers noted, then feeling freely able to choose, and then being provided with, their own book was the best place for patients to start.

Thanks Sara, for sharing this – the thing I always find amazing is the sheer scale of book (and other printed matter) mobilisation during the First World War. The excellent conference that we co-organised with Siobhan Campbell and Edmund King, ‘The Book as Cure: Bibliotherapy and Literary Caregiving from the First World War to the present’, (14 September 2018, details at https://www.ies.sas.ac.uk/events/conferences/book-cure-bibliotherapy-and-literary-caregiving-first-world-war-present) investigated some of these themes, and asked a range of questions in response, not all of them easy for researchers to answer. How does advocacy for the book as a kind of cure work? Who proposes books, and who gets to choose? Is the book promoted to combatants as a cure, or as a drug? And what did readers themselves make of it – did reading help normalise and domesticate the unbearable? You are absolutely right to point out the key role that women like Helen Mary Gaskell played in First World War reading initiatives – this is an almost forgotten part of the war effort and indeed, of women’s history, and your continuing work shines a light on it.

A review of ‘The Book as Cure’ conference by Jenny Cattier (PhD student at Anglia Ruskin University) is forthcoming shortly on the English blog space.