50 objects for 50 years. No 32. Video recordings.

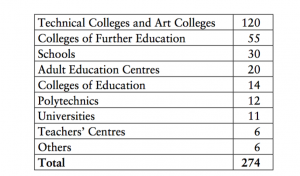

Sunday, November 25th, 2018The OU achieved national, indeed international, fame through its use of television for teaching purposes. However, it was teaching so much that the time allocated to OU broadcasts soon became inadequate. The BBC wanted to broadcast a range of materials. As noted under Object No 31, the number of television transmission slots available to the OU did not grow at the same rate as the number of OU broadcasts. By 1978 about 20 per cent of OU television broadcasts had only one transmission. The percentage of students watching the broadcasts fell and the OU’s Video-Cassette Loan Service was introduced in 1982. As only about 8 per cent of OU students had a VHS player at home, machines were distributed to the regions. OU study centres began to be stocked with collections of videos and replay machines. In 1981 students could attend centres in order to use Europe’s first ‘interactive videodisc’.

Soon the technology spread. By 1986 60 per cent of OU undergraduates had a video player in their homes. Britain had the highest ownership of video-cassette recorders in Europe, and OU students’ access to such technology was ‘well above the national rate’. A survey found that only 14 per cent of OU under- graduates could not arrange access to a machine. In 1992, 90 per cent of OU students surveyed had a VCR and 80 per cent of them recorded OU programmes. From 1993, instead of mailing video-cassettes to students, the OU arranged for the night-time broadcast of programmes for students to record. Video-cassettes liberated students from a fixed viewing schedule. OU Professor John Sparkes argued that ‘it was a mistake to try to teach conceptually difficult material by broadcast TV. It goes too fast and cannot be slowed down to allow for thinking time.’ Using video, students could skim, pause, rewind, fast forward and search. They could integrate reflection on of other teaching media. By contrast, a third of students who watched television material focused on the details and failed to draw out the general principles. For courses with fewer than 650 students each year it was cheaper for the OU to distribute returnable video-cassettes than to broadcast the material. he OU had its own purpose-built television studio complex at Walton Hall. This enabled it to produce a video which generated three-dimensional images of the brain for the Biology: brain and behaviour course. The OU began to produce course-specific, non-broadcast materials (for group viewing at residential schools, for example).

OU videos, unlike broadcasts, were designed for students not general viewers and could be and replayed by the students. The OU considered how best to use the equipment. Research was carried out at the OU into the effectiveness of teaching by non-academic organisations, such as British Telecom (which used interactive video to train managers dispersed throughout the UK) and Price Waterhouse (which used a videodisc-based training programme to acquaint employees with potential computer security risks). An ‘Alternatives to print for visually impaired students: feasibility project report’ was produced for The Mercers’ Company and Clothworkers’ Foundation. A team from IET worked with Rank Xerox EuroPARC in order to design effective computer-based support for collaborative learning where people were located at different physical sites and connected via various forms of technology.

The OU made a number of videos as part of its Continuing Education activities. A video for Talking with young people, P525, included forty- three sequences. Students were invited to watch in groups and consider their reactions. The constraints inherent in a 23-minute broadcast slot did not apply to a video-cassette with a number of independent sections of varying lengths. For Social psychology, D307 (1985–95), students were invited to analyse a drama by referring to letters in the corner of the screen and a grid provided in the video notes. The presenter explained:

watch the excerpt straight through first time, even if you can’t get it all down in your notes, you’ll have a chance to replay this section of the tape later on. Doing this analysis in real time will be good practice for when you do your own observation.39

Similarly, the, video associated with Matter in the universe, S256 (1985–92), included the instruction that viewers should watch it more than once and that they should address questions related to the numbers in the corner of the screen. For Engineering mechanics: Solids and fluids, T331, 1985–2004, students were expected to measure the time period of an oscillating pendulum, and then stop the tape and apply the data to an equation. The impersonal broadcast to an infinite crowd had been adapted to enable personal use by members of the OU’s student body.

By the 1990s for Studying family and community history: 19th and 20th centuries, DA301 (1994–2001), students were encouraged to develop their transferable skills by making audio and video recordings.