The focus in this posting is on the final object of 50 in the series, the people at the heart of the OU, the learners.

The focus in this posting is on the final object of 50 in the series, the people at the heart of the OU, the learners.

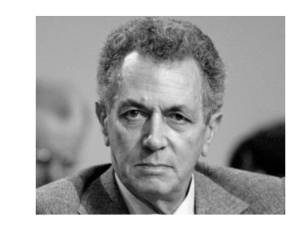

← President Cath. No longer a duck, she fits the bill.

It was contributed by Cath Brown. She is well qualified to write about students. She been a student (she has a BSc in Molecular Sciences (i.e. Chemistry) and a BSc Open (mainly physics, engineering and history) and she is currently studying Computing at the OU. In addition, she has been a STEM Faculty Representative on 2016-18 Central Executive Committee, has chaired an Students Association affiliated society (OU Alchemy) held various OUSA posts and moderated an online forum. Currently she is President of OUSA.

Philip Sully with then OU Chancellor Betty Boothroyd on the occasion of the naming of the building

(Source )

Visitors to the OU’s Milton Keynes campus will see buildings named after many illustrious figures – Perry and Horlock for the first and second Vice-Chancellors, Wilson and Jennie Lee for our political founders, and eminent scientists Alan Turing and Robert Hooke. But the Philip Sully building is the only one (to date) named after a student.

When the building was named in 2006, Philip had completed 61 modules, and his qualifications included two undergraduate degrees, a masters and a doctorate. I somehow doubt he has stopped studying since then – the signs of OU addiction are clear to see!

It’s good to be reminded, in this era in which education is too often seen as solely a means to an end, of the joy and the value of the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake. The Philip Sully building thus serves as a splendid symbol of lifelong learning.

Our 50th object – the building – is here standing for Philip, and by extension all OU students, without whom there would be no university. What have these students looked like over the years?

In the early days, there were a significant number of teachers who’d taken the accelerated post-war training, but were now in search of a degree. These days, there’s still that teaching link – it’s a particularly popular career with OU graduates – but it’s often classroom assistants looking for the degree to embark on initial teacher training.

The OU was once christened the “university of the second chance”. Being told that university was “not for the likes of you” was all too common in days gone by; in 1950 only 3.4% of young people participated in higher education, and this was only up to 8.4% in 1970 and just 19.6% still in 1990. So the OU was the natural destination for many whose background had hitherto prevented them pursuing that degree. Even if they had the formal qualifications for admission to a “brick” university, part-time or flexible courses at conventional institutions were unheard of, so for the employed aspiring graduate, the OU was almost the only game in town.

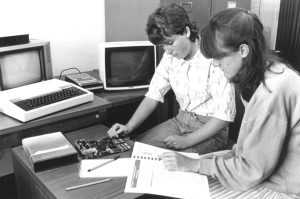

In the 21st century, we are edging up to half of young people entering higher education (though who knows whether government proposals will knock that down again). So there are fewer of the “second chancers”. Today’s “typical” OU student (in so far as such a creature exists) is in their 20s, working, and aiming to improve or change their career. In a surprising move, a fifth of OU students are now studying at full time intensity. Then we have the students with disabilities for whom the OU is a much more feasible and flexible option, and the students who are carers, who can only contemplate studying if they can fit it around the demands of their lives. Many of these students are very time poor – fitting in study around family and work requires taking advantage of any free moment to keep up. Back in the 70s and 80s, OU students rose early and stayed up late to catch their course TV programmes; the videos may be all online now, but just as many students are keeping those same hours to carve out some study time.

But the OU still has students from their teens to their nineties, and any broad assumptions about their motivations, their circumstances and their lives are pretty well destined to be wrong.

So are there still students like Philip around – learning for pure pleasure? Most certainly; the rumours of the death of the “leisure learner” are greatly exaggerated (There is even a Facebook group called “OU Study Addicts” with hundreds of members). In England at least, it’s expensive for a “hobby” now, but there are still students who aim to never leave the OU, some taking advantage of the second degree funding now available for STEM subjects to keep going, others prioritising their studies over more frivolous activities such as holidays!

Of course the OU student experience, like the student experience anywhere, is not just about studying. Many OU students say they’ve made friends for life. In the early days, the tutorial, the summer school and the unofficial local study groups were where connections were made – a fantastic set up if you happened to click with someone local to you. The advent of widespread internet access opened up new additional ways to “meet”; students of the 2000s will remember the FirstClass conferencing system with affection, but 2019 students are more likely to speak of Facebook and WhatsApp.

OU Students Association first President Millie Marsland – clearly a force to be reckoned with! She maintained her job as a Headteacher whilst leading the Association.

Like any other student body, OU students have had their own Students Association for most of the lifetime of the university. The Association (known for many years as OUSA) has (amongst other things) pushed for students to have a greater voice in the university (resulting on representation throughout the governance structure), developed its own support service Peer Support, started its own charity for students in financial need OUSET, and supports a raft of Clubs and Societies, including the strangely named TADpoles. This society was formed by students of the course TAD292 Art and the Environment, chaired by Simon Nicholson, which had its last presentation in 1985…. But the society is still going strong in 2019!.

The Association’s video gives a fuller picture of OUSA history.

What will the OU student of the future be like? Whilst the financial pressures of the day and the demise of the “career for life” suggests that young(ish) career-changers and promotion-hunters may come to dominate our student body, let us make sure that our university always has room for lifelong learners like Philip, and continues to offer that enriching broad curriculum that has changed so many students’ lives.

What will the OU student of the future be like? Whilst the financial pressures of the day and the demise of the “career for life” suggests that young(ish) career-changers and promotion-hunters may come to dominate our student body, let us make sure that our university always has room for lifelong learners like Philip, and continues to offer that enriching broad curriculum that has changed so many students’ lives.