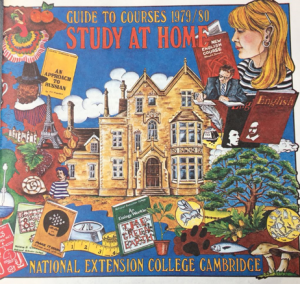

The National Extension College (NEC) was founded by Michael Young in 1963 as a pilot for what he had termed an ‘open university’. He intended for the NEC to be the nucleus of an open university. The NEC would have three functions:

- Improve the quality of distance learning courses for students taking the University of London external degrees.

- Promote a range of learning opportunities through lectures and residential courses

- Teach through a variety of methods including broadcasting.

The NEC did indeed go on to deliver Michael Young’s vision but that is a different article.

The focus of this posting is on the preparatory courses that the NEC developed for intending OU students in the late 1960s.

The Gateway Courses

The Open University was founded on the principle of being open to everyone, irrespective of their background. In practice, however, this could be challenging for those who had little experience or prior knowledge of academic study. This was where NEC came in. In Autumn 1968, NEC launched three pre-degree level courses, aimed at those who were planning to enrol with the OU. In the first year, 4,380 students enrolled on the Gateway courses.

The first three courses were:

Reading to Learn – ‘designed to help you develop your powers of reading selectively and critically’

Man in Society– ‘an introduction to the methods and concepts of social sciences’

Square 2– this built on O-Level Maths.

The first students

The first students

A sample survey of 70 of the initial students was carried out in 1980. They all came from a similar socio-economic background. 90% were aged between 20-40; 90% came from non-manual occupations; and 67% had been to a grammar school, and 50% had had some form of further education.

Richard Freeman, NEC’s director at the time, offered an explanation for the difference between these learners and the ‘second chance’ learners that Michael Young had hoped to reach through the NEC. Freeman argued it was not because of a difference between NEC’s other courses and the Gateway programmes but rather the publicity surrounding the Open University. It was those that had more education who had an awareness of the OU’s existence. As awareness of the OU grew, people took the courses who had no previous qualifications. Indeed, by 1980 there was less of a difference between those who enrolled on NEC’s Gateway courses and those who signed up for other NEC courses.

The feedback from these students was positive. 87% answered that the Gateway course had helped to improve their lives either socially or materially.

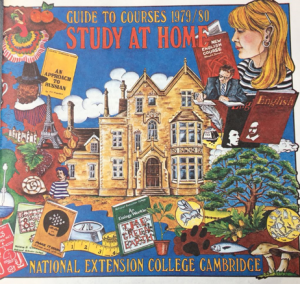

The 1970s

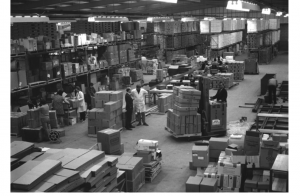

It is unsurprising that the Gateway courses were in high demand in the 1970s. They catered for a previously unserved audience. They were of huge importance to the NEC. By the 1970s, 40% of NEC’s 8,000 enrolments came from the OU preparatory courses.

Individuals within the OU were key in promoting the courses. Naomi Sargant, who had worked closely with Michael Young, before becoming the OU’s Pro-Vice- Chancellor (1974-1978), was a great advocate of the courses. Indeed, she carried out a research project in 1979 looking at the impact of the Gateway courses. The research concluded that those who had studied the Gateway courses were not only more likely to complete their OU degree but they were also more likely to receive higher grades. It was thought this was because the NEC courses prepared students well both for the degree level work but also for studying at a distance. But it could also be argued that it was the most committed and engaged students who were willing to undertake a preparatory course.

Chancellor (1974-1978), was a great advocate of the courses. Indeed, she carried out a research project in 1979 looking at the impact of the Gateway courses. The research concluded that those who had studied the Gateway courses were not only more likely to complete their OU degree but they were also more likely to receive higher grades. It was thought this was because the NEC courses prepared students well both for the degree level work but also for studying at a distance. But it could also be argued that it was the most committed and engaged students who were willing to undertake a preparatory course.

The 1980s

Still, as the OU began to mature, some of its staff questioned why they were advising people to take the NEC’s Gateway courses. NEC’s director, Richard Freeman approached the OU each year to ensure the OU continued to advocate the Gateway courses. The support NEC needed were the three lines promoting the courses in the annual OU undergraduate prospectus.

In 1980, the Gateway courses were revised. The two features that remained the same were the popular course texts and the correspondence tutor. ‘Man in Society’ was replaced with ‘The Arts: A Fresh Approach.’ This course was less academic, less densely written, and had clearer objectives.

NEC’s policy towards OU preparation had changed. Courses were now shorter, they were now more accessible, and based more on student experience. The preparation was not exclusively tailored towards the OU but to a range of possible options.

NEC went on to develop a further set of introductory courses. These were shorter; students would typically spend 20-30 hours on them, not 40-50. One of these courses still survives in the NEC archives. ‘Preparing for Social Science’ was first published in 1982. In contrast to the previous courses, the only reference to the OU is in relation to the problems of distance learning: ‘if you are going on… to an OU course then it might be a good idea to accustom yourself to working to deadlines.’

NEC went on to develop a further set of introductory courses. These were shorter; students would typically spend 20-30 hours on them, not 40-50. One of these courses still survives in the NEC archives. ‘Preparing for Social Science’ was first published in 1982. In contrast to the previous courses, the only reference to the OU is in relation to the problems of distance learning: ‘if you are going on… to an OU course then it might be a good idea to accustom yourself to working to deadlines.’

In 1984, NEC’s three lines were removed from the OU brochure. In fact, the brochure now warned of the additional expenses of preparatory correspondence courses. Without official OU endorsement enrolments on the Gateway courses dropped significantly. This was a major crisis for NEC because it happened suddenly and without prior warning.

This, however, was not the end of the relationship between these two providers of distance education. Applications to higher education, having dropped the decade previously, were once again on the rise. The OU received 60,000 applicants per annum for 20,000 places. Ideas for a merger were discussed in November 1988 in order to help the OU meet demand. Other ideas were proposed such as hosting a joint facility ‘National Centre for Distance Education and Training’.

In the end, however, bureaucracy proved too great and no formal agreement was drawn up between the two organisations. It is, however, testament to the need of distance learning at all levels, that both organisations continue to exist and thrive.

This post was contributed by Anna Gibbons. Having gained a first-class degree in History, Anna will return to Cambridge for an MPHil in Modern British History in October 2018. She worked with NEC over the summer to catalogue their archives and draw up an overview of the college’s history.

Award ceremonies might go better with a bit of pomp, and a mace but the music is always Fanfare for the common man.

Award ceremonies might go better with a bit of pomp, and a mace but the music is always Fanfare for the common man. Many others refer to a sense of achievement and triumph as being collective. When you see the families jump to their feet when their mum takes to the stage, when you hear about juggling of childcare, jobs, family finances, the supportive babysitting grandparents, the partner who brought a cup of tea as the student sat late at night completing that TMA, you come to realise that learning is a collaboration.

Many others refer to a sense of achievement and triumph as being collective. When you see the families jump to their feet when their mum takes to the stage, when you hear about juggling of childcare, jobs, family finances, the supportive babysitting grandparents, the partner who brought a cup of tea as the student sat late at night completing that TMA, you come to realise that learning is a collaboration.