50 objects for 50 years. No 37. Conferencing software.

Monday, December 31st, 2018

The use of technology to promote co-operative and collaborative learning goes back to the earliest days of the OU. Despite initial complaints from the GPO, which ran the UK telephone system at the time, since 1973 telephones were used to support the physically isolated, the itinerant, the housebound and the shiftworkers who were often unable to attend tutorials. Expert strategies were developed and a pack produced. Advice was offered to tutors about encouraging students to gather around a loudspeaker telephone for self-help activity ‘with the added bonus of you taking part from a distance – like an academic Cheshire cat’. Soon audio conferencing, which could involve up to eight people on telephones in different locations, was employed as were faxes, personalised audio-cassette messages and video-conferencing.

In 1988 the OU introduced courses which required students to have access to a desktop computer. It presented Information technology: Social and technological issues, DT200, (1988–94). This used computer conferencing. By 1990 about 2,000 students were using CoSy to communicate with tutors and with other students. Programming and programming languages, M353 (1986–99) required a home computing facility, while Matter in the universe, S256 (1985–92) provided computer assisted learning for home computers and employed interactive videotape. Students were given opportunities to buy or rent computers. In 1995 twenty courses, with a total of almost 21,000 students, required undergraduates to have access to an MS-DOS machine. Conferencing enabled students to select a time which was convenient to them to respond. This did not offer the immediacy of quick-fire debate but it did provide opportunities for reflective dialogue. The large-scale use of this facility on Information technology, DT200, helped to shift the focus within the OU away from the individual learner towards consideration of how best to support social interaction. Individual students were encouraged to construct personal meaning and to contribute to their own learning and that of others through online discussion.

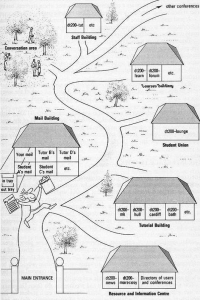

Information technology: Social & technological issues, DT200 (1988–94) introduced many students to computer conferencing with this electronic map of a virtual campus.

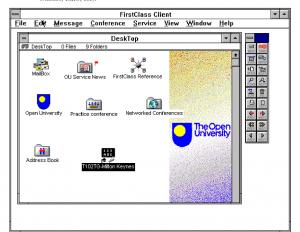

A new text-based conferencing system was developed. In 1994 FirstClass was provided for undergraduate courses following successful trials of the collaborative learning activities that it supported. It was considered to be much more intuitive a system than CoSy and within a year 5,000 students were conferencing. By 1996 there were 13,000 and soon 50,000. Initially the conferencing facility was used for interactions previously carried out by phone or letter. Tutors offered advice and responded to requests via FirstClass. The house-bound and those overseas began to exchange ideas with other students, particularly if conferencing was structured and linked to assessment. The university began to devise guidance for tutors on conference moderation and ideas about conferencing were further developed for an online course You, your computer and the net, T171 (1999–2005), which enrolled around 10,000 students in its first year and had 12,500 students by 2000. In addition to access to an extensive website students received a CD-ROM of software and set texts.

As new ways of providing interactive and individualised support for learners became possible so the importance of maintaining face-to-face contact declined. The OU study centre had begun life as ‘a “Listening and Viewing Centre” with the express purpose of providing access to VHF radio and BBC2’. Used for counselling and other purposes, many initially cost little to rent. The increased use of home video players and desktop computing cast some doubt on the value of study centres.

Typical FirstClass screen, 1996

On Discovering science, S103, computer-mediated communication was optional for students but a requirement for ALs. They used FirstClass to access a national conference at least once a week and they could also exchange messages using conferences designed for the localities in which they were based. ALs were provided with guidance as to how to teach in the interactive seminars and offered practical advice which reflected the ethos of OU teaching practices. It was suggested, for example, that they ‘adopt an informal, friendly tone. Start a message with a greeting such as “Hello” … avoid the more formal “Dear Chris”.’ In addition, they were told that ‘CMC is a medium devoid of warmth and you need to compensate for this’.

Learning was integrated with practice and students were required to submit their work electronically. They communicated not only with the central computing facility but also with one another and their tutors. Groups of about fifteen worked collaboratively on projects in their own tutor-moderated conferences. Reflection was integral to the assessment. Students were required to provide evidence of participation in online discussions. The intention was to use the new delivery modes to ensure that the OU’s environment remained congenial and supportive of the creation of knowledge by learners.

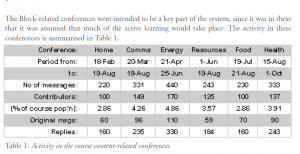

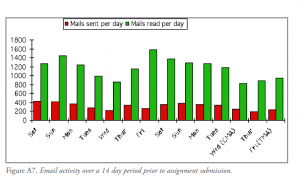

Online conferencing enabled data to be recorded for later analysis of how students learn and which were the most effective teaching strategies. Illustrations from Morris, R.M., Mitchell, N. & Bell, M. Student Use of Computer Mediated Communication in an Open University Level 1 Course: Academic or Social? Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 99, 2, 1999.

Students studying ‘Environmental practice: Negotiating policy in a global society’, D833, used conferencing software Lyceum to represent different specific countries attending a virtual United Nations. They were given the problem of constructing a shared agreement through virtual UN negotiations. Negotiation was presented as an interactive dynamic, social activity and mutual learning process. Students were encouraged to understand both negotiation and how practi- tioners deploy theory through engaging in reflection on the simulation. They were also invited to keep non-assessed negotiation journals. An evaluation of the first presentation suggested that they appreciated the sense of community engendered and the support for reflection. Some of them said that they used the negotiation skills they had acquired in other situations and that they felt empowered by the course. While this module simulated a workplace, the United Nations General Assembly, other courses written for practitioners overtly tied their practical workplace activities to their studies. See David Humphreys, ‘The pedagogy and practice of role-play: Using a negotiation simulation to teach social science theory’, Proceedings of the International Conference on Computers in Education (ICCE) ‘Learning Communities on the Internet: Pedagogy in Implementation’ (Auckland, New Zealand, 3–6 December 2002).