50 objects for 50 years. No 15. The Study Centre

Monday, July 30th, 2018 In the early years study centres were used to show students OU TV programmes.

In the early years study centres were used to show students OU TV programmes.

Study centres were integral to the OU from the start. The 1966 White Paper, formally introducing the OU, proposed that a network of study centres, where tutors could meet students, should be created. The Times fretted that a university education ‘demands direct personal contacts between teachers and learners and even more, among the students themselves. It is doubtful that the network of summer schools and study centres will be able to support it.’ The first Vice Chancellor, Walter Perry felt that in order to function, the OU has to be ‘parasitic’ upon other institutions, notably the WEA and local authorities, in regard to the provision of study centres. He set Regional Directors the task of finding these places. Harold Wiltshire (who was both a member of the Planning Committee and Head of Nottingham University’s extramural department) helped Regional Director Norman Woods to find rooms in the East Midlands. In Belfast one of the first centres was in a school. The Regional Director, Ken Boyd recalled ‘adults getting their knees under grammar school pupil’s desks’. In 1977 the OU’s Dr Ken Jones proposed study centres in industrial premises and the offer of guaranteed places for industrial workers. However, largely centres have been sited in polytechnics, universities and other educational establishments. A 1996 report found that ‘all too often they are in dreary, poorly equipped schools’.

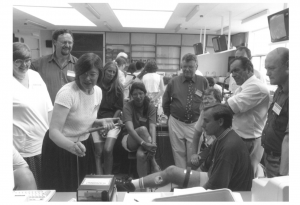

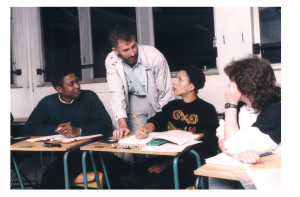

Tutorials in Study Centres. By the 1990s the idea of grouping students around tables so that they could see and talk with one another was commonplace.

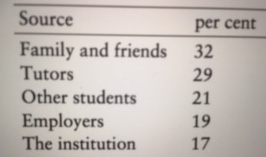

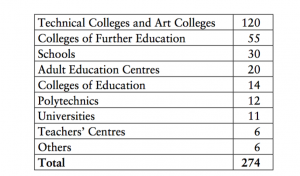

Left is a table of the different types of host institution in 1971.

Perry considered purchasing 280 sets of the 27 volume Encyclopaedia Britannica in order to equip study centres. However, it seemed more valuable to equip them so that users could access a variety of electronic and electrical items. From the first year that the OU presented modules, 1971, some mathematics courses required students to be able to access a computer terminal. On M100, the first mathematics foundation course, 7,000 students were given access to the OU’s mainframe computers via 109 Teletype terminals in study centres and 4 terminals available at summer schools. Access was limited by the scarcity of terminals. One student recalled making a forty-mile round trip ‘to set up a simple query in Basic and then wait ages for the response to clatter back’. My Mum studied M100 and had to go to a local school where students could dial up a computer 50 miles away in Manchester. She reported that she barely got a glimpse of the technology because the male students were so keen to engage with it. Over 10,000 hours were logged by students who learned, through a dial-up service, how to write programmes in BASIC.

Tutorials were often devoted to offering students opportunities they could not otherwise obtain, notably group discussions or engagement with scientific experiments and demonstrations. Study centres began to be seen as potential media resource Centres. Some were stocked with collections of videos and replay machines. Recordings of programmes were made available in study centres, and loans of playback equipment were made. In the 1970s few students had access to such equipment. In 1976 the OU set up the CICERO project with three courses (modules) with online requirements. In 1981 students could attend centres in order to use Europe’s first ‘interactive videodisc’ and there were more than 250 study centres in the dial-up network; most had with Teletype or VT100 terminals. In 1982 about 95 per cent of students lived within five miles of a study centre computer terminal. The ‘connect hours’ increased by 50 per cent due to the introduction of the courses M252 and PM252 ‘Computing and Computers’, studied by nearly 3,000 students.

In 1982 telewriting system or an ‘electronic blackboard’ known as Cyclops was introduced. A telephone line connected to a TV monitor. It enabled drawings made on screens to be seen in other locations. Eight study centres were connected in a two-year trial run in the East Midlands and funded by British Telecom. The tutor could be in a central position in one of the study centres with a group of students there, talking to little groups in another three or four centres.

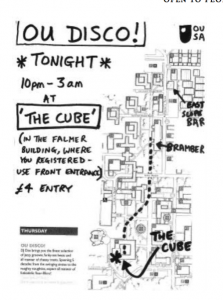

A report in 1996 found that OU study centres, having begun life as ‘Listening and Viewing Centres with the express purpose of providing access to VHF radio and BBC2 and as access to BBC2 and video recordings at home widened it appeared as if ‘the future for study centres is clear … extinction’. However, face-to-face connections between students and tutors have remained popular and they are still used.

Study centres have played a variety of other roles as well. A study centre in the Netherlands was also used by the Dutch OU. In Belfast the Long Kesh Internment Centre, the Maze, had a study centre hut was established inside the prison. It was used by both loyalists and republicans. Martin Snoddon, who called himself a Unionist ‘hardliner’, met a member of the IRA in the Maze when they were both studying through the OU. They became friends and remained in contact after their release. Snoddon, when released, took on reconciliation work and helped to form a group which aimed to reintegrate former political prisoners from both sides into the wider society. Many of the OU’s prisoner students in the Maze went on to hold positions of authority in a variety of community organisations. In 2012 five Sinn Féin Members of the Legislative Assembly in Northern Ireland, a Member of the European Parliament and others in a number of civic roles were OU graduates. David Ervine and Billy Hutchinson were both elected to Belfast City Council in 1997 and to the Northern Ireland Assembly in 1998 and were former Long Kesh Compound prisoners who had completed OU degrees. Both felt that their degrees gave them political confidence and an understanding of methods other than violence.

In 1969 theorist Michel Foucault helped to found the Group d’Information sur les Prisons (Prison Information Group) and within a few years he had conceptualised (in Of other spaces) prison as a heterotopia, that is a ‘place which lies outside all places and yet is localisable’. Such a place could juxtapose ‘in a single real space, several spaces, several sites which are themselves incompatible’. Heterotopias were not utopias, but ‘other places’ in which existing arrangements were ‘represented, contested and inverted’, where individuals could be apart from the larger social group. These locations were both isolated and penetrable, their focus and meaning unfixed. When an OU student, an Irish Republican prisoner called Dominic Adams, referred to the classroom in a prison run by the British by its name in Gaelic, seomra rang, he was not naming it not as a utopia (literally meaning ‘no place’) but an OU-topia which could be almost any place in which the social order could be reevaluated. Many of those who studied with the OU while in prison were able to create a space for themselves which was beyond their day-to-day reality and within which there was a strong sense of the collective. This tendency was so marked that one interviewer noted, ‘a very strong and understandable tendency to tell stories from the collective perspective since this reflects the solidarity of the political organisation […] Sentences would sometimes begin ‘we’ not ‘I’’.

Study centres have been more than sad school rooms, they have been where students came together and, supported by their tutors, created ideas and understandings though collaborative engagement.