50 objects for 50 years: No. 11. The cup which cheers

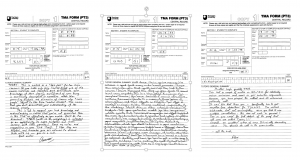

Monday, July 2nd, 2018These images of Student Association volunteers and that cup by the keyboard, remind me of an important aspect of the OU. The cup of tea or coffee brought by the supportive partner late at night when you are completing a TMA. An OU study, Enduring Love? assessed over 5,000 people and found that, as researcher Jacqui Gabb noted, ‘Grand romantic gestures, although appreciated, don’t nurture a relationship as much as bringing your partner a cup of tea’.

Haven in a heartless world?

The word ‘tea’ can refer to a plant, a beverage, a meal service, an agricultural product, an export, an industry or a range of other notions but for those studying with the OU a cuppa can represent how families (in the widest sense) pay an important part in OU studies. Surveys indicate that students frequently acknowledge that their engagement was initially determined by their peers, families and communities as well as their own expectations and experiences. A number referred to how the OU broadened their horizons, increased their confidence and, by enabling them to form communities of learners, helped them become active citizens who could benefit the wider society. It is not always the case. One student recalled her husband’s reaction when he discovered her books and realised that she was studying with the OU:

He threw them all down the rubbish chute (we live on the 7th floor). I get on well with Ted the caretaker so next morning when my husband had gone to work I went to see him and said I had to go through the bins … there I was with big rubber gloves picking my way through everything but I got it all back and cleaned up. I can leave it at my pal’s flat.

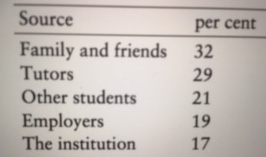

One of the first graduates noted, ‘students need sympathetic families’. Asked to rate the importance of sources of external support OU students placed family and friends at the top of the list. Although some represented their decision to become OU students as individual, often accounts refer to a recommendation from a family member. Here is the results of a survey of sources of external support.

This has adapted from Simpson’s “Supporting students online, open and distance education 2002, p. 120.

Once studying began, the support of families remained important. George Saint believed that ‘My wife shielded me from the demands of a young family’; he chose not to study for Honours because ‘my wife deserved a rest and I wanted to enjoy my children’. Emma’s comment reveals both a realisation about the unhelpfulness of a poor self-image and a changing relationship with a spouse:

Shouting ‘I’m fat and stupid’ at your husband will not make you understand the equations needed to calculate the emissions from an incinerator (though speaking to him nicely means he might just sit with you and talk it over in a very calm and patient manner).

For similar conclusions about the significance attributed to kin, see the online accounts by Charlene Buckley, Vida Jane Platt, Joanne Greenwood, Jim Bailey, Maureen Bowman, Iain Boyle and Mark Pearce. Kayleigh Carey mentioned her husband; Gwen Rowan her boyfriend, later husband; Claire Smith an OU student who was her boyfriend, later fiancé. Ian Ellson was encouraged by his wife and her family, and Patricia Palmer by her husband and children.

Study aid

Pausing for a drink might be when, as you sip you reflect on how tea, coffee and chocolate, initially exotic commodities which arrived in Britain in the seventeenth century, have become drinks of British people of all social classes. Might this help you with your sociology or history assignment? If your beverage is sweetened you might want to consult Steve Pile’s two-part guide to the ‘cultural paradox’ of the ‘geography of sugar’. You might consider the US-based Tea Party. These conservative citizens were funded by Republican business elites, bolstered by a network the conservative media and campaigned against Obama. Might be useful if you are studying politics?

To prevaricate by making one more cup of coffee before entering the ‘valley below’ of actually completing that TMA is a ritualistic delay immortalised by Bob Dylan (One more cup of coffee) who went on to note that you might find that ‘You’ve never learned to read or write. There’s no books upon your shelf’. Tea has also been presented criticised as a barrier to work.

Slogans and reminders

Despite the possibilities for wandering off the point, and not focusing on getting that essay completed, within the OU tea drinking has been encouraged with specialist mugs. This is one produced for the students’ Psychology Society. While there were also mugs made to after the OU had been open for a quarter of a century.

The ‘Keep calm’ one was produced for a staff member by a spouse during a period perceived as being a time of existential crisis for the institution. Alongside it are some cups, also for staff, which remind imbibers of the importance of the UCU trade unio

The ‘Keep calm’ one was produced for a staff member by a spouse during a period perceived as being a time of existential crisis for the institution. Alongside it are some cups, also for staff, which remind imbibers of the importance of the UCU trade unio

Mugs of tea cheer staff and help students storm to success. As the Kinks sang, ‘have a cuppa tea, Halleluja, halleluja, halleluja, Rosie Lea’.

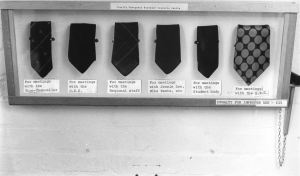

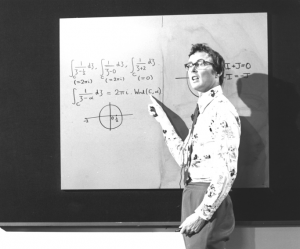

The OU was cast into the mould of the 1970s and 1980s and has found it hard to escape. Creating a new image, renewing the brand, has not been aided by internal jokes which have bolstered the clichés. This Faculty Emergency Neckware Resource Centre, complete with half-a-dozen ties behind glass and a small hammer, suggests that men dominated the faculty, that the Dean of that faculty, Mike Pentz enjoyed the same status as Jennie Lee, one of the OU’s founders, and that there were at least six separate occasions when staff might be required to appear in ties but that the rest of the time, stained lab coats, worn corduroy trousers and sandals worn with socks were the norm. The OU module ‘

The OU was cast into the mould of the 1970s and 1980s and has found it hard to escape. Creating a new image, renewing the brand, has not been aided by internal jokes which have bolstered the clichés. This Faculty Emergency Neckware Resource Centre, complete with half-a-dozen ties behind glass and a small hammer, suggests that men dominated the faculty, that the Dean of that faculty, Mike Pentz enjoyed the same status as Jennie Lee, one of the OU’s founders, and that there were at least six separate occasions when staff might be required to appear in ties but that the rest of the time, stained lab coats, worn corduroy trousers and sandals worn with socks were the norm. The OU module ‘

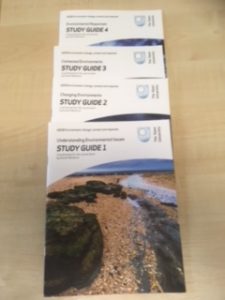

The contents are unknown and there is room for speculation. What is inside? There have been records, cassettes, video disks, computers, models of the human brain and of course study guides. These ones are for U216.

The contents are unknown and there is room for speculation. What is inside? There have been records, cassettes, video disks, computers, models of the human brain and of course study guides. These ones are for U216.