We are proud to announce that this year’ s Peter Nicholls Prize has been awarded by the Science Fiction Foundation to Adam Baldwin. Adam is a fourth-year PhD student here with us at the Open University. He completed his BA and MA at the OU too, so has been with us now for almost 20 years – testament, he says, to the addictive nature of studying here.

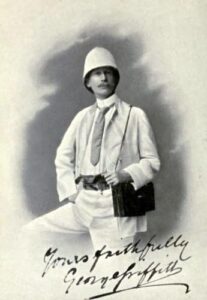

Adam’s PhD focuses on the once popular but now little-known novelist George Griffith, and his role in the development of early science fiction. Adam’s prize-winning essay ‘Secularizing the Destruction of Gomorrah in George Griffith’s Hellville, USA’ will appear in the Science Fiction Foundation’s summer 2023 issue (no. 145).

Today, he shares with us how this fascination began, and where it has taken him.

I have been working on a PhD thesis on George Griffith, a little-known science fiction and adventure writer, as well as journalist and globe-trotter, from the late-nineteenth century and into the first few years of the twentieth. Born the son of a country vicar in 1858, George Chetwynd Griffith-Jones (he changed his name by deed poll to George Chetwynd Griffith in 1894), was an immensely prolific author, writing around 44 novels across multiple genres between 1893 and his early death in 1906 at just 48, as well as a stream of innumerable short stories, poems and articles.

I came across his work around eight years ago when I picked up a modern reprint of his first novel The Angel of the Revolution (1893). I was fascinated by this story of an underground revolutionary group, led by the mysterious and mesmeric Natas, who, having exclusively obtained the knowledge of heavier-than-air flight (the novel is written some ten years before the Wright brothers finally succeeded at Kittyhawk), end a catastrophic world war and go on to impose a world-wide socialist utopia. The edition I read was edited by H. G. Wells specialist Steven McLean, and he ended his introduction with the words: ‘The Angel of the Revolution deserves to wing its way into modern critical consciousness’ (2012).

This comment was made only a couple of years before I read it, and I was interested enough in the novel to see if any work had been done on George Griffith’s work since then. The short answer appeared to be No. There is a handful of modern pieces on Griffith’s writing, but nothing substantial, and he certainly hadn’t winged his way into critical consciousness. I sought out reprints of his novels from small publishing houses and read what I could. McLean’s phrase stayed in my mind, and I decided I would take up his challenge. Luckily, the Open University agreed.

I have been drawn to Griffith’s work not because he is a great writer of extraordinary prose and delicately drawn characters, quite the opposite: Griffith writes thrilling novels, exciting page-turners, full of action, romances in the vein of H. Rider Haggard of King Solomon’s Mines (1885), She, (1886) and Allan Quatermain (1887) fame.

His great innovation was to build on the adventure romance, bringing in various other popular genres: the future-war dramas that followed in the wake of George Chesney’s The Battle of Dorking (1871); utopian writing such as Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888), William Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890) and Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s The Coming Race (1871); the apocalyptic dramas of Richard Jeffries’s After London (1885) or Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826); and the voyages extraordinaire novels of Jules Verne, such as Twenty-Thousand Leagues under the Sea (1869, trans. to English 1873). This combination helped to form the emerging genre of scientific romance, an early form of what is now called science fiction.

All this is set against a backdrop of what Sally Ledger and Roger Luckhurst called ‘an epoch of endings and beginnings…a time when British cultural politics were caught between two ages, the Victorian and the Modern; a time fraught with anxiety and with an exhilarating sense of possibility’ (2013).

Within this new genre framework Griffith examines contemporary anxieties: the fear of invasion, the rise of socialism, the extension of suffrage, both male and female, evolution and degeneration, and the rise of the New Woman, a proto-feminist figure. Griffith’s portrayal of women is fascinating, if complex. Many of his women characters possess an unusual degree of personal agency over their lives and marriage choices for the time. In one extraordinary scene Natasha, the titular Angel of the Revolution, dispatches an unwanted suitor with a well-aimed gunshot to the head.

Natasha despatching her unwanted suitor, illustration by Fred T. Jane, 1893. (This image is in the public domain).

This is no spur of the moment action by a hysterical figure, but calm, controlled, if not quite cold-blooded. The remarkable part of this is that Natasha is permitted to do this, and she does not suffer punishment within the novel for her actions.

Reading further across Griffith’s novels, I frequently found similarly strong, independent female characters. An exploration of these, and how much freedom they actually have, is central to my thesis. Closer reading of the novels shows that women were still subject to patriarchal authority, they were just lucky enough to have father’s and/or erstwhile suitors who allowed these women unusual personal agency.

This may not seem like a great victory for women’s rights, but glance through the works of H. G. Wells, H. Rider Haggard, Arthur Conan Doyle or other adventure writers of the period, and you would be hard-pressed to find a female character who was not merely decorative, or a victim in need of rescuing – often both.

My mission is to rise to Steve McLean’s challenge, slightly modified, and help George Griffith wing his way into modern critical consciousness.

Adam Baldwin is a PhD Candidate at the Open University, studying the role of Victorian writer George Griffith in the development of science fiction. Adam has studied with the OU through his BA and MA since 2004. He is a recipient of the 2023 Peter Nicholls prize for early career researchers, awarded by the Science Fiction Foundation.

Adam Baldwin is a PhD Candidate at the Open University, studying the role of Victorian writer George Griffith in the development of science fiction. Adam has studied with the OU through his BA and MA since 2004. He is a recipient of the 2023 Peter Nicholls prize for early career researchers, awarded by the Science Fiction Foundation.