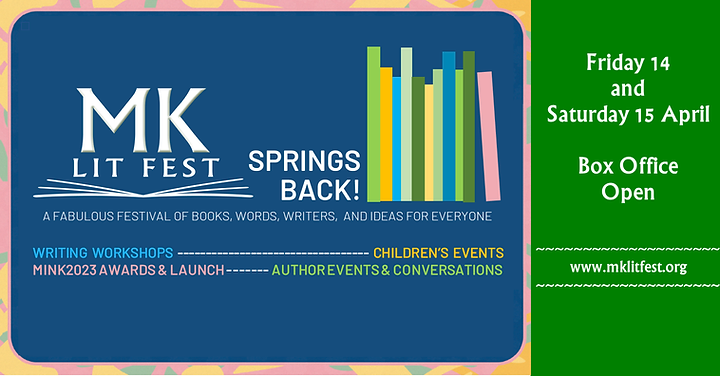

Open University PhD graduand, Patrick Wright, and current PhD student, Gwyneth Jones, acted as judges for Milton Keynes LitFest’s MinK2023 Writing Competition. All the shortlisted entries will be published in an anthology, and the winners will be announced at the Anthology Launch at Milton Keynes Library on 15th April 2023.

To mark the announcement of the shortlisted entries, we caught up with Gwyneth Jones, who judged the flash-fiction categories and is a prize-winning author of flash herself.

What is flash fiction and how did you first discover it?

Flash fiction, in a nutshell, is a very short story. Exactly how short is debateable but certainly less than 1000 words, perhaps as few as 200, and it should feel absolutely complete in itself. Flash can be any genre it chooses. It can dress up, dress down, dress to impress, or go commando. It’s a delinquent midget-gem that resists pigeonholing.

Very short fiction has been around for ever – just think of Aesop’s Fables. But flash fiction really began to gain traction as a genre in the late 1980s. Today it has a wide international fanbase and is published in literary magazines, anthologies, single-author collections, and also, of course, online. The immediacy and connectivity of the internet has proved an excellent forum for these punchy bite-sized fictions.

It was on the internet that I stumbled across flash fiction competitions. Entering gave me a way of finding out if my writing was any good – which it wasn’t at first – but I learned by reading the entries that were better than mine, the ones scooping prizes. After a while, I got hooked, got listed, got published.

As a writer, what attracts you to the form?

The chance to experiment in a way that might not be sustainable in long-form fiction. Flash can be very disruptive, disregarding ‘rules’ about writing, such as having a beginning, middle, and end. Scrap that! Flash hardly gets past the beginning. Flash is always close to the end. You might start in the middle, in media res, or you could squeeze that out altogether and trust the reader to fill in the gaps. Another rule: ‘create original characters’. Or you could use archetypes to save thousands of words. Take Goldilocks: your reader already knows she’s an adventurous, entitled, blonde who’s very, very picky. With only a few hundred words so much is possible; you could write about a nanosecond, a lifetime, or an eon. You could write from an unusual point of view, or in the negative, or in a Fibonacci sequence. Flash can handle some serious subjects, but the form is very playful.

You have won the Wild Words competition and been long/shortlisted for the Bridport, Bath Flash Fiction, Reflex Flash, and the Quiet Man Dave prizes, and now you have judged MK Litfest’s flash fiction competitions. From your experience on both sides of the process, what would you say makes for a prize-winning flash?

A title that works hard – something that interacts with the text; pin-sharp specificity, nothing anodyne, clichéd, or generalised; careful attention to the sound of the words because flash is great for reading aloud; and, of course, absolute economy – not one single wasted word, no lazy word choice. As with all great fiction regardless of size, voice is important. Voice is the thing that snags the reader from the start. It’s in the vocabulary, the syntax, the imagery, and the things left unsaid.

After that, the elusive prize-winning quality is something that’s hard to describe – but you know it when you read it – and you want to go back and read it again, and again. Roland Barthes called it the punctum. He was talking about photographs, but I think it translates. It’s some unexpected detail or moment, some splinter beyond the ordinary subject that pierces you and isn’t easily forgotten. Julio Cortázar talks about this power as a story ‘rupturing its own limits’, spilling out and illuminating something beyond the page. The best flash fictions do this; they remain with you like an earworm or a bruise.

Tell us a bit about some of the flashes shortlisted for MK Litfest.

The theme was ‘Green Spaces in the City’ and there was a lot of inventiveness in the shortlist with some writers speculating on the future and about how our relationship with the natural world might develop. One that made me laugh out loud, was written as an email to mankind, warning of an imminent plant-life revolution. There were also some finely penned observations of present-day concerns including one about a woman with a young child searching for a new home and measuring spaces both urban and green with the span of her hands. My personal favourite came from the younger age category (14-19 years) and it was the shortest by far, just 188 words. A quirkily voiced stream of consciousness that exactly captured the crowding and leaping of thoughts, and how one thing leads to another. It had slant, and resonance, and compression; I just adored it from the very first read.

How has your study at the OU shaped you as a writer of flash fiction?

I’ve learned a lot about the craft of writing and applied that to flash fiction, but the most surprising thing is discovering that a ‘being a writer’ isn’t the solitary endeavour I first imagined. I did an MA in Creative Writing here at the OU and was lucky enough to be part of group of incredible, talented writers; we’re still in touch on a regular basis, swapping work and cheering each other on. Now, I’m doing a PhD, and the circle is smaller, but the support and the camaraderie is every bit as good. My time at the OU has spurred me to get involved and make connections out in the wider world where the flash fiction community is vibrant and welcoming with a multitude of workshops, discussion groups, and festivals. I’ve benefitted enormously from the advice and generosity of other writers, and hope to pay that forward. But still, all this sociability and joining in is learned behaviour; if I wasn’t a writer, my dream job would be lighthouse keeper.

Gwyneth Jones lives in Wales and writes short and flash fictions. Under the pen name Jupiter Jones, she is the two-time winner of the Colm Tóibín International Prize, and her stories have been published by Aesthetica, Brittle Star, Fish, Scottish Arts, and Parthian. Her first novella-in-flash, The Death and Life of Mrs Parker was published by Ad Hoc Fiction, the second, Lovelace Flats by Reflex Press and the third, Gull Shit Alley and Other Roads to Hell by Ad Hoc. She is currently a PhD candidate at the OU researching form and narrative purpose in the novella-in-flash.