Two Decades, Two Encounters: From Gardner to Perkins and the genuine fun of the Whole Game

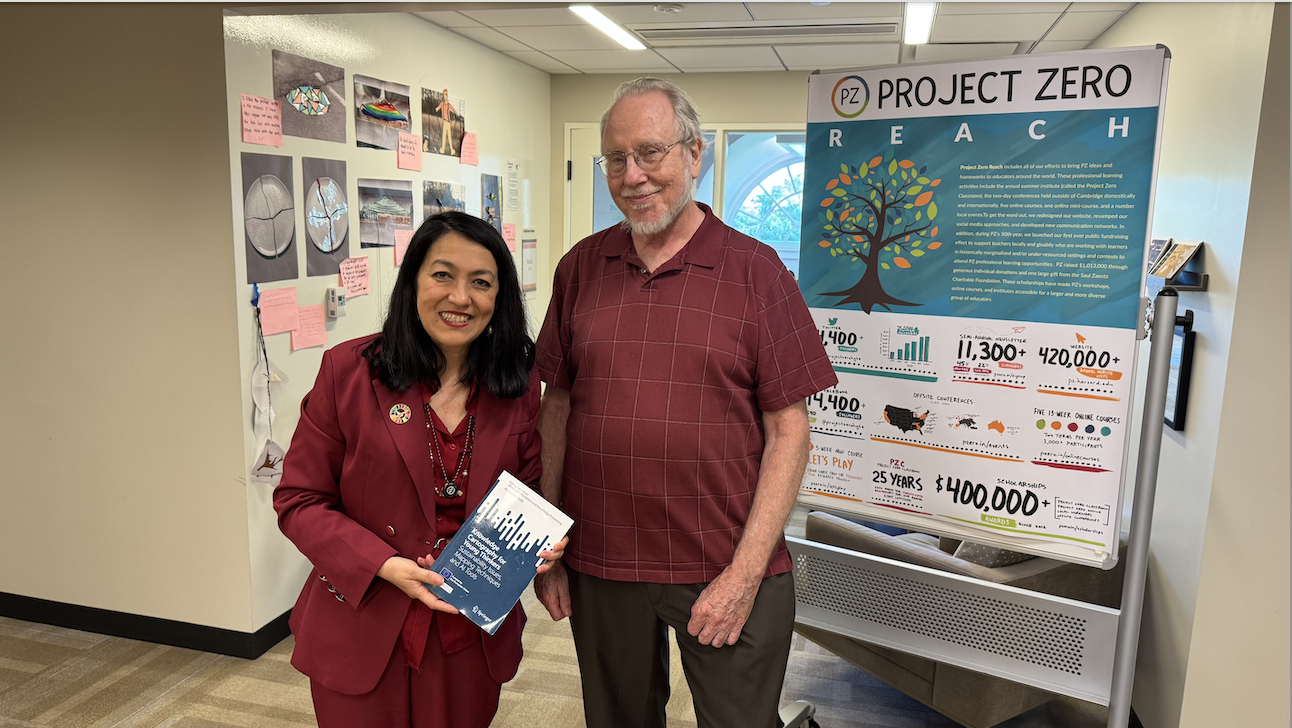

I met Howard Gardner in the early 2000s, just as I was discovering Project Zero through work at the Open University. The encounter left an impression that would shape my thinking for years to come. Two decades later, I had the wonderful opportunity to sit down with David Perkins at Harvard University— and suddenly, the circle felt complete.

Project Zero was launched in 1967 at the Harvard Graduate School of Education by philosopher Nelson Goodman, an enthusiast of the arts who sought to establish firm knowledge about arts education — hence the whimsical name, starting from zero. Founding members Howard Gardner and David Perkins directed it for many years, leaving a profound legacy in educational research. Gardner became famous for Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences (1983), which revolutionized how we understand human capabilities. Perkins authored Knowledge as Design (1986) and Making Learning Whole (2008), offering a practical framework for authentic learning.

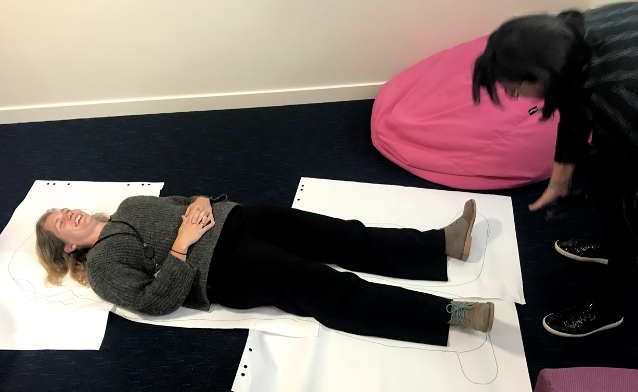

Image 1: Howard Gardner, Alexandra Okada and Tony Sherborne at The Open University UK

Image 1: Howard Gardner, Alexandra Okada and Tony Sherborne at The Open University UK

Image 2 Alexandra Okada and David Perkins at Harvard University, USA

Image 2 Alexandra Okada and David Perkins at Harvard University, USA

For several decades, Gardner and Perkins led Harvard’s Project Zero, conducting transformative research in education. Their collaboration addressed artistic knowledge, creativity, ethics, and the nature of human potential — laying foundations that continue to shape educators worldwide.

Perkins’ Theories Helping Me Advance CARE–KNOW–DO

Perkins identified two common “diseases of learning” in education:

Elementitis: Learning disconnected bits without the whole game. Children memorize times tables without solving real problems, students drill grammar rules without writing texts that matter, and learners know musical scales but never play a full song.

Aboutitis: Learning about something without actually doing it. Students read about science experiments instead of performing them, and learn about entrepreneurship from textbooks rather than launching real initiatives.

Perkins argues for engaging with the “whole game” from the start, through simplified but authentic versions of real practice. His call to move beyond these diseases is a reminder that learning must be authentic, holistic, and transformative.

Understanding the Whole Game

As we talked, something clicked for me. The core parts of CARE–KNOW–DO were not just a sequence — but dimensions of the whole game itself. And when you play the whole game, learning stops feeling like work and starts feeling like fun.

Connecting the Principles

With my notebook in hand, we sketched the connections. Perkins lays out five core learning principles:

- Play the whole game – Experience the complete, authentic activity.

- Make it worth playing – Connect learning to real-world purpose.

- Work on the hard parts – Focus effort where challenges often arise.

- Play out of town – Transfer skills to unfamiliar new contexts.

- Uncover the hidden game – Reveal underlying strategies and thinking

These principles align meaningfully with CARE–KNOW–DO:

CARE – Motivation & Value

Perkins stresses “make the game worth playing.” Learners need to see purpose, relevance, and meaning — not just deferred rewards. When students care about real-world problems like local pollution, climate change, or social justice, the meaning is immediate and real. And here’s the secret: when learning matters, it becomes genuinely fun. CARE compels learners to value the whole game and engage with it fully.

KNOW – Understanding & Knowledge

Perkins highlights how “elementitis” and “aboutitis” fragment understanding. Learners must “uncover the hidden game” — grasping big ideas, cognitive strategies, and conceptual models that clarify authentic practice. His “theory of difficulty” calls educators to anticipate misconceptions and tacit challenges. In our projects, students learn ecosystems and pollution science, but more crucially, they learn how to investigate, question their own assumptions, and build knowledge together. KNOW is about grasping rich knowledge structures, far beyond isolated facts.

DO – Practice & Application

Perkins advocates for “play the whole game” (even in junior versions) and “work on the hard parts” through deliberate action. Authentic engagement means solving problems, experimenting, creating, and performing — not just describing them. Education must prepare learners to “play out of town,” transferring skills to unfamiliar contexts. In our work, students don’t just learn about environmental activism; they practice it. They tackle genuine difficulties: persuading officials, organizing teams, presenting data convincingly. DO means practicing authentic activities and building competence through real action.

The Framework in Action

In short:

- CARE provides motivation — learners see why it matters

- KNOW enables understanding — learners grasp key ideas

- DO builds practice — learners develop capability by doing the whole game

CARE–KNOW–DO is a transformative, co-learning framework. It equips students and communities to care about real problems, know through inquiry and collaboration, and do through meaningful action. This framework evolves across projects like weSPOT, ENGAGE, CONNECT, and METEOR.

The Moment of Recognition

Sitting with Perkins, I realized: co-learning becomes whole only when caring, knowing, and doing unite. That’s when transformation happens. Learners don’t just acquire skills; they become more fully themselves.

What I’m Taking Forward

Perkins’ philosophy of “learning as a whole” is the foundation for CARE–KNOW–DO. Both frameworks share a conviction: learners should engage with the whole game from the very beginning. As Perkins challenges “elementitis” and “aboutitis” by insisting on authentic learning, CARE–KNOW–DO builds a practical pathway — connecting motivation (CARE), knowledge (KNOW), and practice (DO) for truly empowering, transformative education.

The whole game is not a distant goal. It’s where learning should begin.

That’s what Perkins helped me name: We don’t prepare students to play the game. We invite them in and play together.

The plastic-polluted river, the climate data, the community challenge — these are not examples to analyze after mastering basics. They are the basics. They’re the whole game, ready to be played by everyone, even beginners. And that’s where the real fun lives — in the authentic doing, the genuine struggle, the moment when learning comes alive.

Even by all of us who are, in the end, still learning.

This encounter reminded me why I fell in love with education research. It’s not about building better filing systems for knowledge. It’s about helping humans become more capable, more caring, more fully alive.

Thanks, David and whole PZ team, for the conversation I’ll be unpacking for years to come. And thanks, Howard, for starting me on this journey two decades ago.

Image 3: Project Zero Team – Educating with the world in mind as well as “heart and soul!”

Image 3: Project Zero Team – Educating with the world in mind as well as “heart and soul!”

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books.

Perkins, D. N. (1986). Knowledge as design. In H. M. Collins (Ed.), The knowledge system in society (pp. 99–120). Ablex Publishing.

Perkins, D. N. (1992). Smart schools: From training memories to educating minds. Free Press.

Perkins, D. N. (1994). The intelligent eye: Learning to think by looking at art. Getty Publications.

Perkins, D. N. (2008). Making learning whole: How seven principles of teaching can transform education. Jossey-Bass.

Perkins, D. N. (2014). Future wise: Educating our children for a changing world. Wiley.

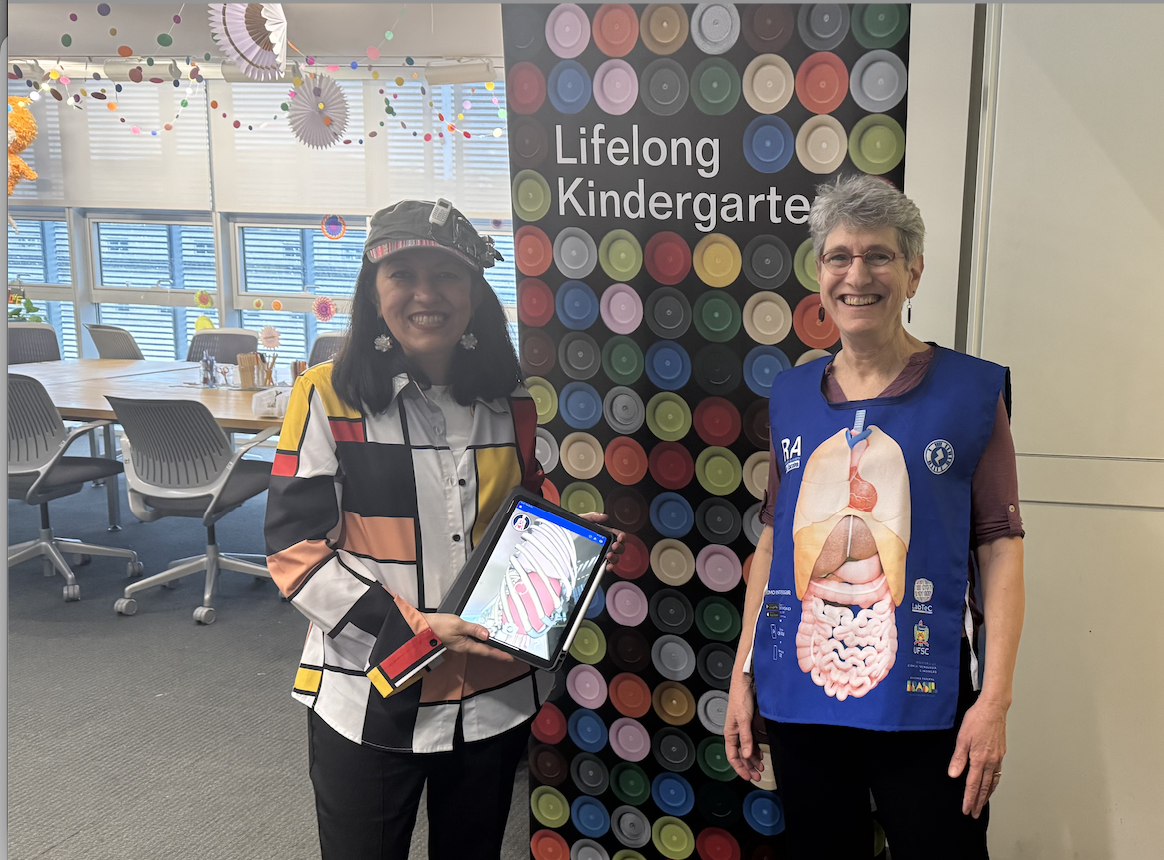

Image 1: Dr. Okada and Dr. Valente at the MIT Media Lab – Lifelong Kindergarten

Image 1: Dr. Okada and Dr. Valente at the MIT Media Lab – Lifelong Kindergarten

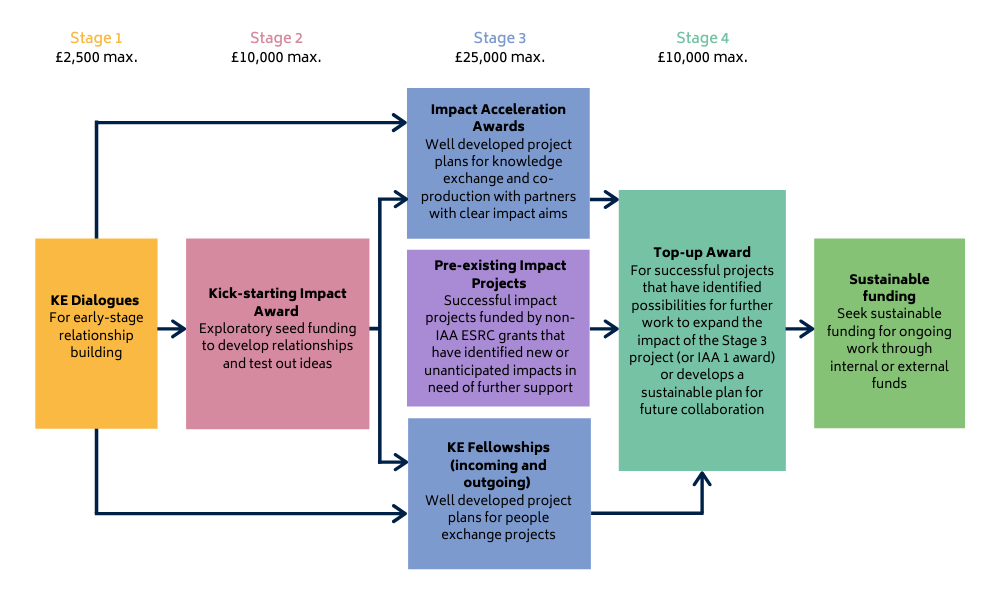

Lorna explained that this funding will help the OU staff to develop close relationships with Oxford and Reading colleagues. The scheme requires that Oxford academics lead on grants submitted but the OU and Reading researchers can participate in the co-creation process and contribute to the proposal as partners.

Lorna explained that this funding will help the OU staff to develop close relationships with Oxford and Reading colleagues. The scheme requires that Oxford academics lead on grants submitted but the OU and Reading researchers can participate in the co-creation process and contribute to the proposal as partners.