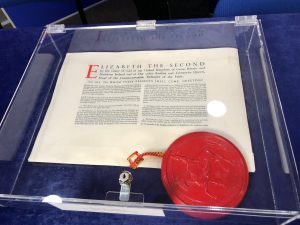

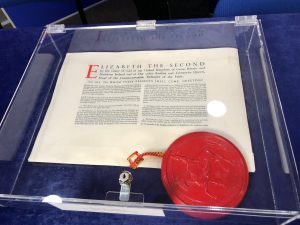

Today 23 April 2018, is the anniversary of the granting of a Royal Charter to the Open University. A year hence it will be the 50thanniversary of the Open University. To mark that half century, we will be writing about 50 objects which have made the OU. You are invited to make proposals for your favourites. Maybe it was the first parcel you received with OU materials or the gown you wore to your OU graduation. Perhaps it was the coffee that your partner brought you at midnight as you struggled to complete a TMA.

This week the object is the Royal Charter. Written by the OU’s Planning Committee it provided the OU with a bulwark of respectability against its detractors andunified the OU into a single legal entity. It unites learners and staff, indicates that this is an institution of quality and it frames how we address, construct and bolster communities. It reminds us of how the OU has united strangers and supported co-operation between learners.

Higher Education institutions do not require Charters in order to confer degrees or to operate. Many have not got Charters and some were only granted Charters after they opened. The University of Essex admitted its first students in 1964 and was granted a Royal Charter in 1965. The University of Keele was founded in 1949 and only received its Charter in 1962. The BBC has a Charter, but it has to be renewed every decade. The incorporation by a Royal Charter (alterable onlyby the agreement of The Queen in Council) gave considerable status to the OU when it was an institution without any students, which was to be based in many sites, which was of unproven popularity with the electorate and which was distained by many MPs. The OU’S Royal Charter proclaims respectability, community, outreach.

Although it was not clear in 1963, when Harold Wilson called for a university of the air, that there would be a new university with its own charter, the idea gained ground as Wilson’s rough notes were expanded and the OU was planned. One reason for a Charter might have been to prevent the Open University’s enemies closing it down when the Labour government lost power, as it did a few months after the Charter was granted. William van Straubenzee, the Conservative junior minister for higher education in the 1970–74 government, was reported as saying of the OU ‘I would have slit its throat if I could’. He blamed the outgoing Labour education minister Ted Short for some ‘nifty, last-moment work with the charter that made the OU unkillable’.

On 23 April 1969, two days after a human first walked on the moon, the Royal Charter of The Open University was granted. The Charter stated that ‘the objects of the University shall be the advancement and dissemination of learning and knowledge by teaching and research by a diversity of means such as broadcasting and technological devices appropriate to higher education, by correspondence, tuition, residential courses and seminars and in other relevant ways’.

The OU’s Charter was based on that of Warwick University, opened in 1965. In its emphasis on openness, the OU echoed the motto of another new university, Lancaster (opened 1964): Patet omnibus veritas (Truth lies open to all). The first stated objective about the need to advance and disseminate learning and knowledge, was similar to statements in the charters of other universities of the 1960s. York’s focus was on enabling ‘students to obtain the advantages of University education’; Lancaster wanted to use the ‘influence of its corporate life’; and the University of Warwick has almost identical wording to these two.

The OU’s Charter contained an additional objective: ‘to promote the educational well-being of the community generally’. It was this obligation to the wider community that led to the development in the 1970s of the ‘Continuing Education’ programme with courses such as P911 ‘The first years of life’ and P912 ‘the pre-school child’.It is this same obligation within the charter that informs continued University collaboration with the BBC on current popular programmes such as Child of our time, Coast and Civilisations.

The Charter set out the regulation of the university. There would be a Council, ‘the executive governing body of the university’, a Senate and a non-executive general assembly, ‘the organ through which the feeling of a corporate institution would be generated’. The university also had its own regional organisation. At first it was It was intended that the General Assembly, representative of both students and staff, would elect representatives to the Council and Senate through regional assemblies. Changes to the Charter have been suggested. These are difficult to make and have led to lively debates.

The Charter did not grant the OU autonomy, the university’s finances were subject of close government scrutiny from the beginning. It was forbidden to carry over income from one year to another unless the expenditure was for the development of teaching materials. The OU could not accumulate reserves, nor own property against which it could borrow money and it was subject to annual review.

The Charter obliged the university ‘to make provision for research’. However, when the OU sought to make provision for postgraduates it was derided by Rhodes Boyson, a head teacher who was to become a Conservative MP in 1974. He argued that the OU only wanted to do this ‘because it expects that no one will accept its degrees as worthy of postgraduate extension’. Despite the difficulties and scepticism, research played an important role at the OU from the beginning. Steven Rose, the OU’s first professor of biology, established the Brain Research Group which was importance in the development of the new field of neuroscience. He recalled that, when offered a post at the OU ‘made it very clear at the start that I wouldn’t go unless there were research facilities … this was going to be a university like any other university’. He received funding from the Medical Research Council, ‘so from the very beginning … we’d actually got research going’. The OU awarded its first PhD in 1972.

Since the first Charter the OU has launched its own Student Charter.