Recognising that a ‘very eccentric institution is a university funded directly by the state, and run by a direct grant from the state’, as noted John Pratt of the OU in 1970, Whitehall, which was an object of significant influence, is this week’s object.

The number of UK universities more than doubled from 20 to 43 during the 1960s but, unlike other new UK universities, the OU, opened in 1969, was not part of a plan developed by the existing committee or was the result of lobbying by local authorities or interest groups. The decision to create the university was made before the main site for it, Milton Keynes, was decided and indeed before concrete started being poured to construct the new city of Milton Keynes. Rather, the British parliamentary system enabled a relatively small number of people to work through Ministerial fiat. The OU has been called the ‘pet scheme’ of the Labour Party Prime Minister and is said to be marked by his, Wilson’s ‘personal imprint’. Being directly controlled by the Minister, rather than being run through the same committee that other universities were, the OU was subject to debates in Parliament and closer investigation than other universities. The OU took the form it took because of the interventions of Labour Minister Jennie Lee. After Labour lost power in 1970 the new Conservative Minister, Margaret Thatcher, sought to amend the entry rules to encourage greater competition and the government directed the OU to support various overseas ventures as part of its diplomatic efforts. It buttressed open learning institutions in The Netherlands, Nigeria, Surinam and Thailand. It sent teams to Iran, Pakistan, it helped the Israelis to establish an Open University.

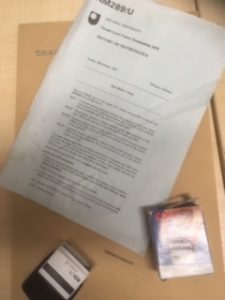

As a university created by central government and directly accountable to the Department of Education and Science the OU was subject to frequent scrutiny of its activities, budgets and teaching materials. The OU grant was reviewed annually and the OU was forbidden to carry over income from one year to another unless the expenditure was for the development of teaching materials. In addition, the OU could not accumulate reserves, nor own property against which it could borrow money. Formally, there was little scope for errors in budget management. However, costing such an innovative venture was difficult and in practice there was some flexibility. This was perhaps in recognition that the OU was not treated as other universities were. It was not within the remit of the University Grants Committee. The OU’s first VC, Walter Perry noted that, ‘our financial health has been maintained not so much because of lucky budgetary guesses in those early years but because of the extremely understanding and sympathetic way in which the Department of Education and Science (DES) has viewed our problems’. It was crucial that the fledgling university was not directly competing for funds with powerful and unsympathetic conventional universities.

As the university became more established, the demerits of this mode of funding began to outweigh the benefits. It was difficult to plan over the medium term because of the numerous challenges which required immediate resolution. Short-term resource allocation, in response to specific events or initiatives, was favoured, as, according to VC John Horlock, ‘it mattered to our masters at the DES when £500,000 was overspent one year (from a budget of well over £100 million)’. There was also concern that funding decisions were made on party- political grounds. John Horlock complained that ‘the civil servants liked to have their fingers in the OU pie, whereas I hardly saw a civil servant in all my time at Salford’ (where he had previously worked). He also noted that while the government determined student numbers, discouraged research and denied proposals for postgraduate funding, ‘ventures close to its own policies’ received support.

A Visiting Committee was appointed in order to advise the minister on the financial and other plans. Between 1982 and 1990 it was chaired by Sir Austin Bide. It was a period when the amount of government grant per undergraduate fell by over a quarter in real terms. Its eleven members visited a summer school and Walton Hall in 1982 and proposed improvements to the assessment system, which were implemented. Its recommendations led to changes in staffing, acceptance that the OU should continue to engage in research and that there should be a change in the funding arrangements. When the OU sought to expand postgraduate teaching and to fund some undergraduate-level courses in the continuing education programme through the core funding it had to make its case through the Visiting Committee. Sir Austin Bide was also a member of the Croham Report on the University Grants Committee which, as part of a wider brief, reviewed the relationship between the OU and the University Grants Committee. It received evidence from the OU’s Vice-Chancellor and others at the OU and did not recommend the integration of the OU. It did, however, propose the replacement of the University Grants Committee by a group half drawn from outside the world of education.

During the 1980s, Keith Joseph, Secretary of State for Education 1981–86, adopted the view that the impact of the university-educated elite of the UK had been economically detrimental as it was wary of commercial and industrial activity. Keith Joseph’s 1985 White Paper, The Development of Higher Education into the 1990s, envisaged a smaller higher education sector. The sector, meanwhile, responded to the prevailing climate by consciously adopting industry-based models of management, which were endorsed in the Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals’ 1985 Report of the Steering Committee for Efficiency Studies in Universities. The Committee, which was chaired by industrialist Sir Alex Jarratt, emphasised an enterprise culture and specific managerial styles and structures. It also called for improvements to strategic planning and resource allocation within all universities and proposed performance reviews. This framework was already relatively familiar to the OU. It argued that it had already created structures which were in line with the recommendations of the Jarratt Report, notably a Vice-Chancellor’s Management Team and a Senate and Council connected to the Strategic Planning Resources Committee. Other universities took steps to implement its main recommendations. In the development of its management systems the OU was in some respects further down a path which all universities would have to follow.

The ease of access to OU materials and the direct line between the university and the national civil service enabled a number of Ministers to comment on OU teaching materials over the course of a decade. On being told that a social science course showed a Marxist bias in its critique of monetarism, Sur Keith Joseph read all the relevant teaching materials, visited the OU and summoned the University’s Vice Chancellor ‘to what proved’, the VC John Horlock recalled ‘to be a very difficult interview’. Anastasios Christodoulou (the University Secretary, 1968–80) said that the Minister ‘didn’t like the OU at all’ and thought that the OU ‘was politically motivated, ideologically unsound and its standards suspect and I’m almost quoting’. In 1988 the government the body which administered funding to the universities was abolished. This ‘buffer’ was replaced with that which academic Robert Anderson described as ‘more feeble barrier against direct state control’. The OU was joined by other universities in a new system. It no longer enjoyed a near-unique status within Whitehall.

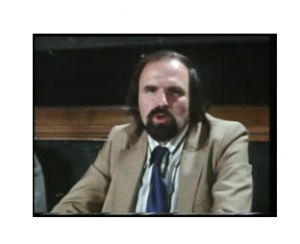

The court, to be found around the back of the Gardiner Building, is named after Michael Drake, the first Dean of Social Sciences. He is also why Social Sciences courses are prefixed ‘D’. He recalled how in late 1968 or early 1969 the VC’s Committee of the OU (now the VCE) met.

The court, to be found around the back of the Gardiner Building, is named after Michael Drake, the first Dean of Social Sciences. He is also why Social Sciences courses are prefixed ‘D’. He recalled how in late 1968 or early 1969 the VC’s Committee of the OU (now the VCE) met. the local history society and his recollections have appeared in the local press. A longer recording has been made for the OU Archives. Much of his research and teaching focused on the population studies (he studied half-a-million baptism, marriage and burial records from Morley Wapentake, Yorkshire as part of an early project). He wanted to bring elements from the social sciences together with elments from the traditions associated with historians.

the local history society and his recollections have appeared in the local press. A longer recording has been made for the OU Archives. Much of his research and teaching focused on the population studies (he studied half-a-million baptism, marriage and burial records from Morley Wapentake, Yorkshire as part of an early project). He wanted to bring elements from the social sciences together with elments from the traditions associated with historians.