50 objects for 50 years. No 43. Examination papers

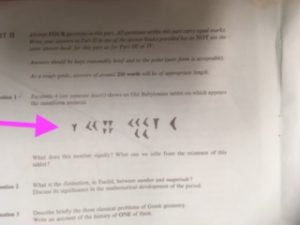

Monday, February 11th, 2019Stamps and papers: This examination paper, from a second level module ‘History of Mathematics’ was sat on 30th October 1979. For one of the Questions students were invited to look at the cuneiform numeral and were asked ‘What does this number signify?’.

The OU issued Examination and Assessment Boards with rulers and green pens so that a clear line could be drawn on the print out which delineated which students were in each category. Of greater interest to at least some Board members (mostly those with a barely suppressed desire to be that caricature of librarians or with fond memories of a John Bull printing press) was the other item in the picture. It is the stamp which was used at the meetings of the Examination Boards. ‘Considered by the Board’ meant that a script had been taken from its place in the files, assessed by one or more Board members and sometimes regraded.

Back in 1979 at many universities the external examiners would arrive each summer, look over some Finals papers and approve the assessment processes. At the OU there was a concern that the university was not seen as having the same status of other universities and that students writing their TMAs out of sight of their tutors might have received unacknowledged help. Although there were many other ways to assess, the unseen examination paper came to dominate. The shift away from the model of a course in which six assignments constituted half the overall marks and a three-hour unseen exam constituted the other half, took a long time. This model, it was argued, would counter the possibility of cheating. The OU came under criticism because, being open, it was easy to learn from it. Having listened to some OU radio broadcasts philosopher Roger Scruton claimed that one OU sociology course was ‘certainly biased’ and concluded that a student ‘who learns to write a perfect examination answer in Marxism’ would be rewarded. He also claimed that OU students’ minds ‘are neither impressionable nor truly open’. In the face of such remarks the OU employed external examiners for every module. Often these examiners would spend a whole day considering scripts and marks and the general standard of work. In 1971 the examination budget was £130,000 and this had risen to £220,000 by 1973. As it took only 10 per cent of a Foundation course cohort to be on an examination borderline for the results of 600 individuals to be reconsidered, the OU swiftly resorted to the use of computers. However, human beings remained central. Through its extensive use of external examiners and assessors the OU sought to maintain parity of standards with other institutions. Today the concerns that the OU sought to allay have spread. The ‘essays mills’ problem (buying material to pass off as your own) is rife across many institutions and there have been cases of personation in examinations. Many universities use software to check that electronically-submitted work is not copied.

Ian Price was stationed in Bagram, Afghanistan, on the day he had to take a German oral exam. The Ministry of Defence permitted him to make a call and he did his oral examination over the phone. Despite the telephone being cut off twice, he passed. Whether the exam is being sat in a quiet hall, in a prison, under fire in Afghanistan or on a Polaris submarine, what has not changed since my mother sat the examination pictured (her marginalia is preserved on the paper) is that sense of dread. Although her Headteacher wrote to say that she was likely to succeed, my mother left school a few months before she could matriculate. This was so that she could come to England, which was then at war. By the 1970s her ideas about exams must have been hazy. Many OU students would have last sat an exam at school and would not have passed. Those memories can intrude. Richard Baldwyn recalled ‘the dreaded [OU] exam’ which led him to be ‘transported back some fifty years’. Michael Hume felt that the OU helped him to overcome ‘the huge mental blocks A levels were giving me’. In its early years the OU employed Tutor-Counsellors. They were responsible for all first-year tuition (they assessed assignments) and counselling on the broader educational needs of the student. Student counsellor Peter Grigg remembered the first years of the OU and how ‘One student had to be helped to the examination hall, his state of mind being such that his grip on the stair rail had to be forced free to get him to the room.’ Student Christine Smith recalled that the evening before the exam ‘I panicked and phoned my tutor and said I couldn’t do the exam – I just couldn’t revise – I knew nothing. Very patiently she talked me through what I had to do and convinced me of how much I did know and gave me the confidence to take the exam. I passed’.

The OU wants to reward success and examiners (human being who have sat many exams themselves) consider that under examination conditions people often panic. Statistically, if you make it to the examination hall, you are very likely to pass.

All best with your assessment.