There are two buildings which have been named after Jennie Lee on the Walton Hall campus. A library which she opened, now demolished and a building which is the home of the educational technologists at the OU. Jennie Lee House, Edinburgh, is where the OU in Scotland is based. Despite this recognition by the OU itself, sometimes Jennie Lee has been eclipsed. A recent article by Pete Dorey, Vol 29, no 2 2015, in the journal Contemporary British History about the foundation of the OU was entitled ‘”Well, Harold insists on having it!”The political struggle to establish the Open University, 1965-67’. The first line of the abstract reads ‘The establishment of The Open University has been widely lauded as Harold Wilson’s most successful policy achievement and his enduring legacy, a view with which Wilson himself concurred’.

One of the myths about the OU is that it has a single founding father, Harold Wilson. Promoted by Wilson himself who told a story, many times, of jotting down the idea just before settling down to that Great British institution, Sunday lunch in East 1963. The dominant narrative is of the Great Man and his swift creation, between 1963 when he penned the idea and its opening in 1969. There are precedents for such myths in many origins stories. It was clothed in classical garb by David Sewart, onetime Director of Student Services and Professor in Distance Education at the OU. He felt that the OU was ‘like Athena springing fully grown and fully armed from the head of Zeus’; it ‘appeared to have no mother and never to have had the opportunity to have been an adolescent, let alone a child’.

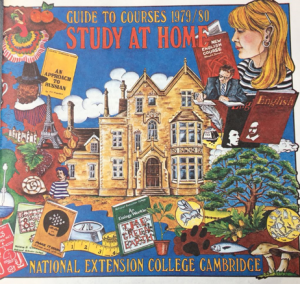

This categorisation of the OU as Harold Wilson’s ‘pet scheme’ (as The Times called it) marginalises the depth of its roots in the traditions of part-time education for adults, developed from the eighteenth century, correspondence courses, associated with the rapid industrialisation of the nineteenth century and on university extension initiatives, which started in the 1870s. It has also developed ideas derived from sandwich courses, summer schools, radio and television broadcasts, for which there were precedents in the twentieth century. It also marginalises the role of Jennie Lee, the OU’s ‘midwife’, to use a term employed by MSP Claire Baker. The sentence in Contemporary British History written by Pete Dorey and quoted above, goes on to say that the policy of having an Open University was ‘was mostly drafted and developed by Jennie Lee’. Dorey also adds that ‘The Open University only became established due to Lee’s dogged determination and tenacity’

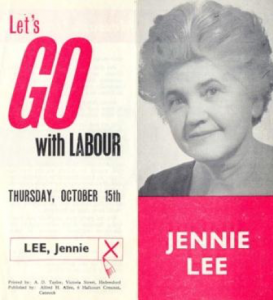

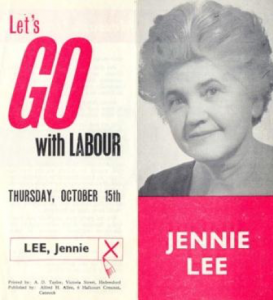

In 1963, Wilson then Leader of the Labour Party, in opposition called for a university of the air. He didn’t fill in the details and, after the General Election of 1964, he was busy being Prime Minister. He handed the brief to a Labour MP who had over 20 years of experience of the Commons: Jennie Lee.

In 1963, Wilson then Leader of the Labour Party, in opposition called for a university of the air. He didn’t fill in the details and, after the General Election of 1964, he was busy being Prime Minister. He handed the brief to a Labour MP who had over 20 years of experience of the Commons: Jennie Lee.

On the campaign trail in Bristol in 1943, where Jennie Lee was defeated, and Cannock which she represented 1945-70.

She became Britain’s first Arts Minister in the Labour government of 1964. She was 60, widowed for four years and fearless. She seized responsibility of making an idea of ‘a university of the air’ into a reality. Keeping well clear of the civil servants who dealt with other universities, it was she who decided on the form the new institution would take. In the face of opposition she developed a tiny sketch into a complete university. As she said to her senior civil servant, Ralph Toomey, in 1967, before the OU had opened, when its future was uncertain: ‘that little bastard that I have hugged to my bosom and cherished, that all the others have tried to kill off,will thrive’. She was able to do this because she had a clear idea of what she wanted – a ‘great independent university’ based on something like the Scottish system of higher education. A coalminer’s daughter who had received a bursary to study at Edinburgh University during the 1926 strike which impoverished her community she determined to beat the established order at its own game, to ‘outsnob the snobs’, as she put it. Her late spouse, Aneurin Bevan, had become a miner on leaving elementary school and had received little formal education, though he noted in 1952 how he valued ‘superior educational opportunities’. She mentioned him when she spoke of the origins of the Open University, recalling how they both knew ‘that there were people in the mining villages who left school at 14 or 15 who had first-class intellects’. This may have led her to create an advisory committee which did not include representatives from the principal university providers of adult education. In addition, she maintained control. She not only created but chaired the committee.

There were plenty of sceptics. Many Conservatives largely hated it. The BBC had long produced educational materials and was unimpressed by this upstart. Whitehall was also snooty and the press largely agreed. Within the Higher Education sector several critics argued that the money should be spent elsewhere. Jennie Lee produced a White Paper before the 1966 general election. Wilson recalled her contribution when the Cabinet met at Chequers 50 years ago just prior to March 1966 election. He said:

At the end of the afternoon anybody was free to speak on anything. Jennie got up and made a passionate speech about the University of the Air. She said the greatest creation of the previous Labour government was Nye’s National Health Service but that now we were engaged on an operation which would make just as much difference to the country. We were all impressed. She was a tigress.

Her Feb 1966 White Paper, ‘A University of the Air’ made it clear that “There can be no question of offering to students a makeshift project inferior in quality to other universities. That would defeat its whole purpose”. She got it into the manifesto, Labour won the election in March and, returned to office, she steered the proposed OU past the sterling crisis, past tax increases, past credit restraints & the prices and incomes standstill and towards her friend, Lord Goodman. He produced a set of figures for the cost of the OU which were a massive underestimate. The OU’s first Vice Chancellor called it ‘perhaps a fortunate accident’. Perhaps. Or perhaps it was an astute political move.

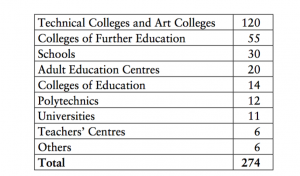

What today would derail a Minister – rudeness to colleagues, indifference to her Secretary of State, visible contempt for the department in which she was located – were her strengths. She didn’t care if civil servants, or colleagues, were offended, or wouldn’t work with her or didn’t trust her. She wasn’t building a career. She wanted an Open University. It was Jennie who decided that the OU would offer degrees, would be open to all, even the unqualified and would operate independently, separately, and with the highest academic standards. Adult education should be more than what she called ‘dowdy and mouldy… old-fashioned night schools … hard benches’. She knew that Adult Education was, as the OU’s first Vice-Chancellor, another Scot called Walter Perry, put it, ‘the patch on the backside of our educational trousers’. In 1965 she told the Commons: ’I am not interested in having a poor man’s university of the air, which is the sort of thing which one gets if nothing else is within our reach. We should set our sights higher than that.’

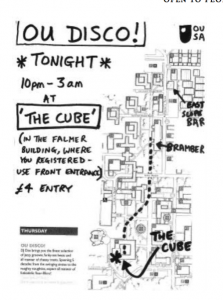

In Walton Hall there is a painting of Jennie Lee. She is portrayed as being in many places at once, including in the Commons, at the hustings and attending a degree ceremony. This is how it should be for, as the Founding Chancellor said when opening the OU, ‘This University has no cloisters – a word meaning closed. Hardly even shall we have a campus… the University will be disembodied’. The OU is everywhere around us and, being without its own body, it needs our bodies.

In Walton Hall there is a painting of Jennie Lee. She is portrayed as being in many places at once, including in the Commons, at the hustings and attending a degree ceremony. This is how it should be for, as the Founding Chancellor said when opening the OU, ‘This University has no cloisters – a word meaning closed. Hardly even shall we have a campus… the University will be disembodied’. The OU is everywhere around us and, being without its own body, it needs our bodies.

Not merely to conceive, but actually to make happen a university which sought to match the standards of the best in the sector but had no admission requirements, which attempted to employ print, correspondence and television in a way which transcended the potential of each, which made a reality of reaching every kind of learner in every corner of the United Kingdom, required a vast act of faith and a bloody-minded determination.