- Advertisements in trade journals indicated the benefits of machines which could support learning.

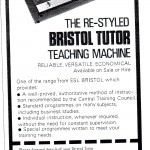

A popular at the time when the OU was being created was that machines could be used to support students learning at their own pace. It appeared possible to create systematically designed step-by-step courses with clear evaluation of the learning objectives. From before the war psychologists had showed that animals appeared to learn effectively when their learning was accompanied by rewards and Sidney Pressey had invented a keyboard-operated teaching machine which was supposed to allow students only to acquire new material once they had mastered the previous steps. Although there was not much interest in such machine in the 1930s, the ideas were adapted in the 1960s as interest in scientific management grew. This appeared to facilitate scientific control over the labour process. Programmed instruction was based on a behavioral model of learning that emphasized prompting for behaviors and responses that could then be reinforced (or not) and used to guide the learner through the course materials. Programmed instruction, later programmed learning, was popular in the 1960s. James Finn’s work at University of Southern California, connected programmed learning to audio-visual facilities and on behavioral psychology. There was also work by Arthur A Lumsdaine and Robert Glazer (eds.) Teaching machines and programmed learning, NEA Publications 1960 to which Burrhus Frederic Skinner contributed. The latter argued that the learning process should be divided into a very large number of very small steps and rewarded offered to the successful. He created a mechanical teaching machine. A learner could respond to a series of questions studied at their own rate. There was a reward for a correct response. The student had to compose an answer as there were not multiple choice answers. There were prompts and hints for students. The intention was to bring a single person into contact with a large number of students and a programmed instruction movement developed. Susan M Markle was an early exponent of Skinner’s programmed instruction in her work at the University of Illinois.

In the UK a Central Training Council was created in 1964. It promoted programmed instruction in industrial training and a survey in 1966 suggested that the idea of programmed learning was now accepted within industry. Universities also took it on and in 1966 Association of Programmed Learning formed. By 1968 it was being used in at least 29 universities in the UK. Electronic systems were developed such as the Edison Responsive Environment, known as the ‘talking typewriter’ and audiovisual material was also used. Programmed learning was used in a variety of trades and by the armed services. It was also used within teacher training.

During the1970s the idea fell out of favour, being deemed to be too mechanistic and rigid because programmed learning units and computer marked tests gave the student no chance to question the ‘teacher’ or to ask for elucidation. Cognitive approaches were becoming more popular within psychology and more flexible regulatory regimes were becoming more familiar within industry. Possibly, ‘there was a gendered effect in programmed learning, with conception and design being largely male areas, while delivery was more mixed’.’ (John Field, ‘Behaviourism and training: the programmed instruction movement in Britain, 1950-1975, Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 59, 3 September 2007, p.326). As the popularity of the socio-constructive paradigm for instruction grew, interest in supporting collaborative learning, social networking and virtual worlds developed.