As Brexit approaches and the UK’s relationship with the EU shifts, this week’s object which can be employed to illuminate the history of the OU is Continental Europe.

The Award Ceremony at Versailles , 2014

The OU has been teaching within the UK since 1971 and in other parts of Europe since 1972. The arrangements for teaching students outside the UK have undergone several changes in that time. Between 1972 and 1992, the University served three broad categories of student studying within the wider Europe: those starting their studies in the UK, those admitted under ‘special schemes’ in the Benelux countries and in the Republic of Ireland; and Services personnel and their families admitted under special schemes in Germany and Cyprus. In 1992 when the European Single Market was introduced, the University extended direct entry to any person domiciled in the EU and in other parts of western Europe.

The first organised move into western Europe was in 1982. During 1981 a Working Group established by the Student Affairs and Awards Board on study provision for those resident overseas issued its report. The report contained proposals, that were accepted by Senate, on the means by which the University’s provision for those resident outside the UK might be rationalised and extended.

The first step in the scheme would be the presentation of a small core of courses, not including ones with Home Experiment Kits or summer schools, drawn from the associate student programme. As the scheme developed, gradually more courses could be added to this initial core and the scheme extended geographically. Ultimately, the courses might be offered to foreign nationals.

Having approved the general arrangements, Senate gave its consent to a specific proposal to offer OU courses to UK nationals resident in Brussels. Five courses were offered in 1982. Applicants had to apply through the British Council in Brussels which would place a block booking with the University and arrange for the subsequent distribution of course materials to students. For all other purposes, students would be attached to an OU region and would have their tutors and counsellors within that Region.

In the event, 45 students registered. After consultation it was decided that all students in the scheme should be attached to the University’s Northern Region: students were therefore allocated to course tutors in that region, and the region was also able to recruit and appoint two associate student counsellors in Brussels. The course tutors did not solely act as ‘correspondence’ tutors: they were able to visit Brussels on two occasions to hold day schools. In 1983 the scheme was expanded to ten courses and made available to non-British nationals in Belgium.

The OU’s presence grew. It came to offer prisoners in western Europe the same modules that were offered to those in British gaols. Peter Regan, a senior counsellor and the manager for Spain Portugal, Greece, Belgium and Gibraltar, recalled although the Vice Chancellor travelled to the continent to present awards to students, ‘we didn’t take many orders from Walton Hall; they didn’t intervene in our European operations’ and that students in prison received support from OU staff. Sometimes informal arrangements were made, on one occasion an Italian nun smuggled TMAs in and out of a prison. Liz Manning, a senior counsellor, and country manager for Germany, Austria, Switzerland and France arranged for a tutor to travel from Vienna to a remote prison in Austria to tutor ‘Michael’. On graduation permission was granted for him to travel to Vienna to receive his degree certificate from Liz: ‘I made a speech to an audience of our office staff, a former fellow prisoner, the British Consul General and his [Michael’s] social worker. We then went out for lunch before he returned to prison’.

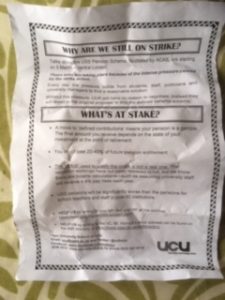

By 2002 were about 6,000 OU students registered in western Europe (‘OU title fails to convince’ Times Higher September 27, 2002). However, the end of the Cold War saw a reduction in interest in western European unity and, with a new OU Chancellor who had not reached the position through holding an academic post, the balance between a recognition of the importance of the market and the benefits of promoting egalitarian values were thrown into a different perspective. Minutes from a July 2011 meeting of the governing body show the university’s vice-chancellor Martin Bean confirmed that the institution was planning to “decommit from face-to-face tuition using (associate lecturers) based in Europe”. There were over 100 academics in nine countries and seven academic-related staff members in six countries supporting 9,000 students studying OU courses in English in mainland Europe. As well as support from a tutor, some had access to online forums and face-to-face tutorials depending on their location. A report concluded that European operations were ‘expensive and inefficient’ and in February 2012 Council took the decision to reduce face-to-face operations and focus on online delivery. OUSA voiced its concerns about the change. Roger Walters, president of the OU branch of the University and College Union, said the plans were ‘deeply regrettable’ and added that ‘It is extremely sad that very many long-standing and highly committed people who have performed an invaluable service for the OU are at risk of losing their jobs… We believe this is a bad move that could damage the [university’s] reputation in Europe’.

While Residential schools continued to be offered outside the UK the OU’s financial director Miles Hedges, noted that the pattern of distribution of OU students across Continental Europe made it difficult to operate the tutor/student allocation process efficiently. The result was that many associate lecturers had tutor groups where few, if any, students were based in their own country. Moreover, the OU had to operate 12 different payroll systems, deal with 12 different legal and fiscal systems and there were high social security costs and fluctuating exchange rates.

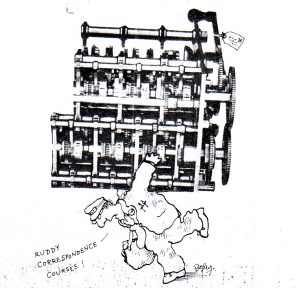

The Times Higher 26 February 2012 found an Associate Lecturer who worked on the Continent

It’s already such a cliche to moan about the gradual decline of higher education’s values as it adopts a more ‘businesslike’ approach that it might seem superfluous to add yet one more voice to the tired old chorus of complaint. Certainly the current direction being taken by the OU is far from unique in this respect. Indeed, it might even be argued that by working for the university in mainland Europe – where students have always been obliged to pay full fees – one is already conniving in a kind of ‘expansion of the customer base’ that is fully consistent with such a market-oriented culture. And yet at the same time, even under such circumstances, many OU staff on the Continent still maintain a certain commitment to some of the idealistic, egalitarian values on which the institution was founded – values such as universal access to learning, which, as we can testify from our everyday work, can be life-transforming. It’s these values that some of us fear are being eroded by this ongoing cultivation of a more openly commercial mindset. The latest cost-saving measures, which will have a massive impact not only on our livelihoods but also the whole quality of student support on the European mainland, are a clear case in point.

Europe remains a major interest to the OU. There are modules which provide opportunities to study it, for example the history module A327, and there have been events for students, such as this one. There is Brexit guidance here. Many staff have assessed the likely impacts of Brexit and the subject features on a second level Politics module.

‘A society grows great when we plant trees in whose shade we shall never see’.

Meticulously designed and planted, ‘the garden symbolises the generosity of donors, commencing with white perennial flowering plants, then bursting into full colour to indicate progress and fruition. As the legacy is living and long lasting, so is the garden. White is still present throughout the flowering seasons to remind us of the gift’.

Meticulously designed and planted, ‘the garden symbolises the generosity of donors, commencing with white perennial flowering plants, then bursting into full colour to indicate progress and fruition. As the legacy is living and long lasting, so is the garden. White is still present throughout the flowering seasons to remind us of the gift’.