50 objects for 50 years. No 41. Trade Unions

Monday, January 28th, 2019After negotiations reaching back to 2002 the new contract for Associate Lecturers (ALs) is going to be implemented over the next two years. This was after 93% of AL union members who voted in a union ballot, favoured the new contract. Casual labour has long been an important element of staffing at the OU. In the past it was only when students signed up for a module that the ALs to teach them are employed. If the number of students fell then, although efforts were made to avoid this, ALs might not be contracted. The new, permanent contract for over 4,000 ALs will mean more job security for tutors, as well as better terms and conditions, more staff development opportunities, and improved long term planning. The Vice-Chancellor, Prof. Mary Kellett spoke of this being ‘a huge step towards an inclusive OU family and a united teaching workforce’. UCU regional official Lydia Richards said: ‘The new contract is a huge step forward for associate lecturers at the Open University. It means they are free from the fear of being out of work if there is a fluctuation in student numbers’.

In the light of this development, this week’s object is the trade unions at the Open University. Members of a number of unions have worked at the OU. Currently two trade unions are recognised at the OU. UNISON was created in 1993 through the merger of a number of unions, including the National Union of Public Employees, founded 1905. It negotiates on behalf of Secretarial and Clerical, Industrial Production Staff and Manual and Ancillary staff at the OU. This includes members who work for private contractors on an OU location. In addition to employment Terms and Conditions UNISON offers advice and support regarding Leave Entitlement, Health and Safety, Bullying and Harassment and it also offers services such as Insurance, Holidays and Legal Advice. Based at Walton Hall, it has representatives at all the OU locations. These include Walton Hall, the Regions, the Nations and the Wellingborough Warehouse.

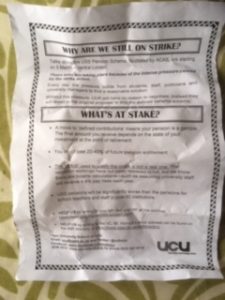

At Walton Hall the pensions strike picket line, Princess Leia, sporting her bagel-style haircut, helped with the leafleting. Strikers were also supported by the local prospective Labour MP, Cllr Hannah O’Neill.

The OU branch of the University and College Union negotiates with the University’s management on behalf of academic, research, AL and academic-related staff. It encourages staff to have a voice in the strategy and future of the university. Fifty years before the OU received its Royal Charter the Association of University Teachers (AUT) was formed. In 1949 the Scottish AUT (formed 1922) affiliated to the AUT (UK) as the AUT (Scotland). Almost from the start the AUT was active within the OU. It was joined by the Association of University and College Lecturers in 1992 and in 2006 it merged with the National Association for Teachers in Further and Higher Education (NATFHE) to form the University and College Union (UCU). The union’s trained caseworkers have provided support and advice to members on a wide range of issues. Unreasonable treatment, such as bullying, discrimination and unfair dismissal have been challenged. There have been campaigns about the gender pay gap, job losses, casualisation, excessive workload and many other issues. The union has not simply been reactive. It has encouraged members to work together and to imagine how education could be better. There has also been support from the central officials and representatives of the union. Following votes, members have gone on strike with other branches around the country, most recently over pensions. Whilst most UCU branches have a membership based in one campus or a single town, the OU branch has Associate Lecturer and Staff Tutor members across Britain and Ireland. The UCU has often campaigned to defend students, opposing the decision to introduce high fees for learners. It has, in turn, received support from students. When tutors have explained that their reasons for postponing the assessment of students’ work, they have received letters and emails of support.

Specially-produced clothing to promote a campaign at the OU.

There have been other initiatives to engage with trade unions and industrial workers. In 1977, in an OU television programme and an internal paper Dr Ke Jones drew on his own research in order to demonstrate that education was perceived as middle class He proposed study centres in industrial premises and the offer of guaranteed places for industrial workers. (Ken Jones, Given half a chance: A study of some factors in cultural disadvantage affecting the acquisition of learning skills in adults). The OU has also been in partnership with Unionlearn, the learning and skills organisation of the Trades Union Congress which helps trade unions provide opportunities for their members to learn.

There have been other initiatives to engage with trade unions and industrial workers. In 1977, in an OU television programme and an internal paper Dr Ke Jones drew on his own research in order to demonstrate that education was perceived as middle class He proposed study centres in industrial premises and the offer of guaranteed places for industrial workers. (Ken Jones, Given half a chance: A study of some factors in cultural disadvantage affecting the acquisition of learning skills in adults). The OU has also been in partnership with Unionlearn, the learning and skills organisation of the Trades Union Congress which helps trade unions provide opportunities for their members to learn.