Joanne Reardon, Lecturer, Creative Writing

The popularity of writing retreats has grown and grown over the past few years: retreats masquerading as holidays where not much writing is done, teaching retreats where you get a writing tutor thrown in, retreats where you can be totally alone. The most important thing is solitude, the space to write where you are given your own desk and your own room and the promise that when you leave you might be on your way to creating your greatest work. I’ve been on two this year: at Gladstone’s Library for a weekend and the Arvon Foundation’s Clockhouse Writing Retreat in Shropshire where, for the past few years, I’ve spent a week each August writing and thinking in the kind of solitude that allows me the kind of creative freedom I just don’t get every day.

Retreat in the traditional sense has always indicated some kind of withdrawal to a secluded, quiet place where we might find silence but where we might also find isolation. In a world where the common cure for loneliness means creating ever more connections, this kind of isolation where we spend time alone with our thoughts can seem a frightening place to be.

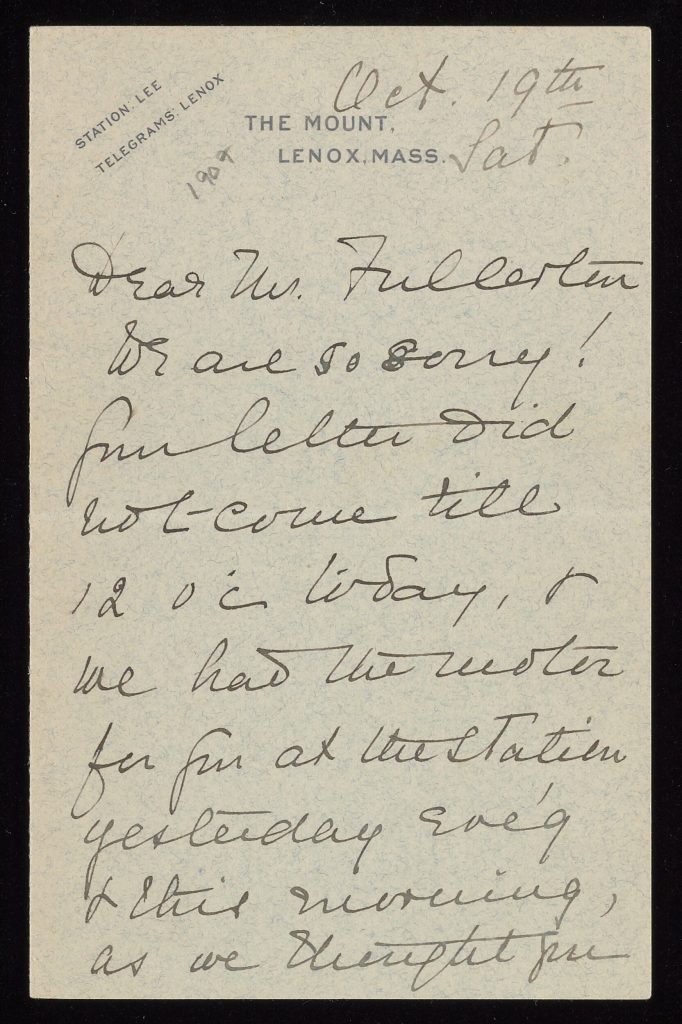

I recently discovered Michael Harris’s book Solitude, in pursuit of a singular life in a crowded world which examines the idea of solitude as ‘a resource’ which can be ‘harvested and hoarded’ and to which there are ‘benefits to maintaining’ so that it might enrich us. Solitude he says is ‘a fertile state, yet one we have a hard time accessing’ (Harris, M. (2017) p.29). This idea of solitude is always on my mind at this time of year because October always seems to me like a month for contemplation. The psychiatrist Anthony Storr writing in 1988 explains in his book Solitude that ‘nearly all kinds of creative people, in adult life, show some avoidance of others, some need of solitude’ (Storr, A. (1988) p.146). This suggests the imagery of an artist tucked away in her studio, the writer trapped in a garret and these are the clichés that jump into people’s mind whenever a writer talks about having private space in which to write or indeed of needing it. Sara Maitland has written a great deal about silence and the retreat into being alone and in her book How to be alone talks about ‘being fascinated by silence; by what happens to the human spirit, to identity and personality when the talking stops, when you press the off-button, when you venture out into that enormous emptiness’ (Maitland, S. (2014), p. 7).

Some years ago, I attended a silent retreat at Loyola Hall in Widnes near Liverpool which turned out to be a transformative experience and taught me for the first time the value of silence and of living with only my thoughts, which weren’t good at the time, for company. The place felt isolated even though it was virtually on the hard shoulder of the M62 motorway near Warrington. There were pylons which ticked like crickets running through the wild, untended grounds and in the woodland which closed the hall off from the outside world, a dog was said to roam, hiding from the owner from whom it had so cleverly escaped. I spent hours walking, looking for the dog – a King Charles spaniel apparently; I spent hours sitting in the lounges, eating in silence; I spent time reading and thinking. It’s when you disappear into your own head that you worry you will find the madness you’ve been hiding from all this time and the surprise is that the opposite can happen. It surprised me and at the time I think it saved me. Several years later I was commissioned to write a short story to accompany some paintings in Warrington Art Gallery only a few miles from the hall. I decided to set my story there making the fictional place into a retreat for people broken by life which was exactly how I had felt when I set foot in there myself. ‘My Mind’s Eye’ was about a singer suffering from PTSD following the loss of her daughter in a car accident, she exists in the company of other people broken by life and slowly through the power of isolation and then through comradeship, the healing begins.

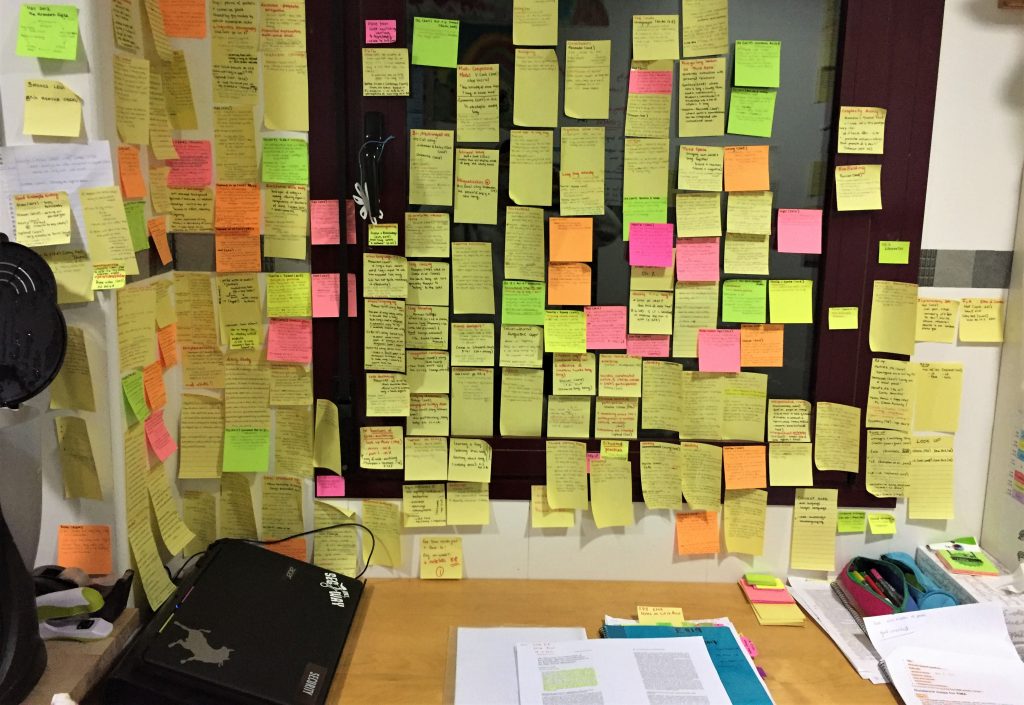

Michael Harris talks about the power of daydreaming where to retreat needn’t be to remove oneself to a physical place for a length of time because every day can deliver moments where being alone can ‘allow for the drifting, unfocused mind to be inspired’ (Harris, M. (2017) p. 54). This kind of retreat is often the most productive not only to find peace but also, I’ve found, as an essential part of writing. It’s the place where ideas begin and this is something I’ve been writing about for just over a year now in my own blog A Writer Retreats where I explore the idea of retreat being as simple as gathering leaves in an autumn garden or walking up an Alpine hill in the darkness listening for wolves. Somewhere there’s a story out there, in the space between thinking and doing. Retreat brings me back to myself when I feel like things are slipping away and connects me to my creative self.

It seems as if I’m not alone in feeling like I want to retreat at this time of year. On Mental Health Day on October 10th last week, I was on a train coming back from Liverpool when some volunteers from The Samaritans boarded the train to hand cards out for people who might need them. I was struck by how many people refused then went back to staring at their phones, out of the window, looking away. ‘We can offer a retreat when you think the world has forgotten you,’ one of the volunteers said in answer to someone who had engaged them in a conversation. I took a card, looked out of the window, the rain beating against it in the darkness, all those lights in tower block windows and so many people in there on their own and thought about Michael Harris’s words that ‘True solitude – as opposed to the failed solitude we call loneliness – is a fertile state, yet one we have a hard time accessing’ (Harris, 29). How can we tell the difference and what do we do if we can’t?

Harris, M. (2017) Solitude, in pursuit of a singular life in a crowded world London: Random House

Maitland, S. (2014) How to be alone London:Macmillan

Storr, A. (1988; reprint 2005) Solitude New York: Free Press