Shafquat Towheed, Senior Lecturer in English

[Image 1: The Africa Museum, Tervuren, Belgium]

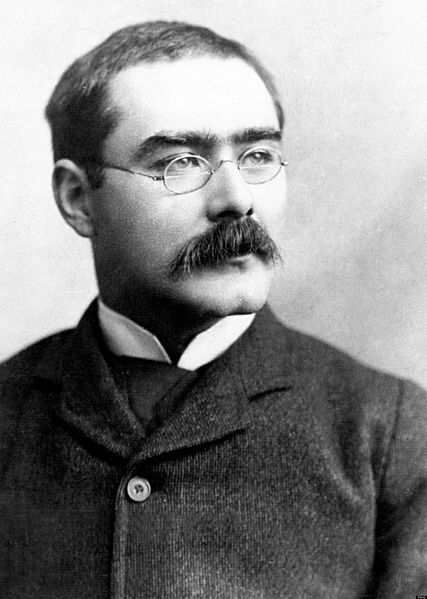

‘In a very few hours, I arrived in a city that always makes me think of a whited sepulchre’, said Conrad’s Marlow about his return to Brussels in Heart of Darkness (1899). Following in Marlow’s (and Conrad’s) footsteps and carrying with me a well-thumbed copy of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness to re-read on the journey, I recently stopped in Brussels on the way to Africa. For me, this was a trip with special significance, for perhaps more than any other single work, it was Conrad’s searing indictment of colonial exploitation, fashioned in the form of a quest romance, which first introduced my teenage mind to the possibilities of literary fiction. Before encountering Conrad, as a child I had been an avid reader of encyclopaedias, National Geographic magazine, books of adventure and factual travel writing, but not of high ‘literary’ fiction. In essence, Conrad was my introduction to the literary canon.

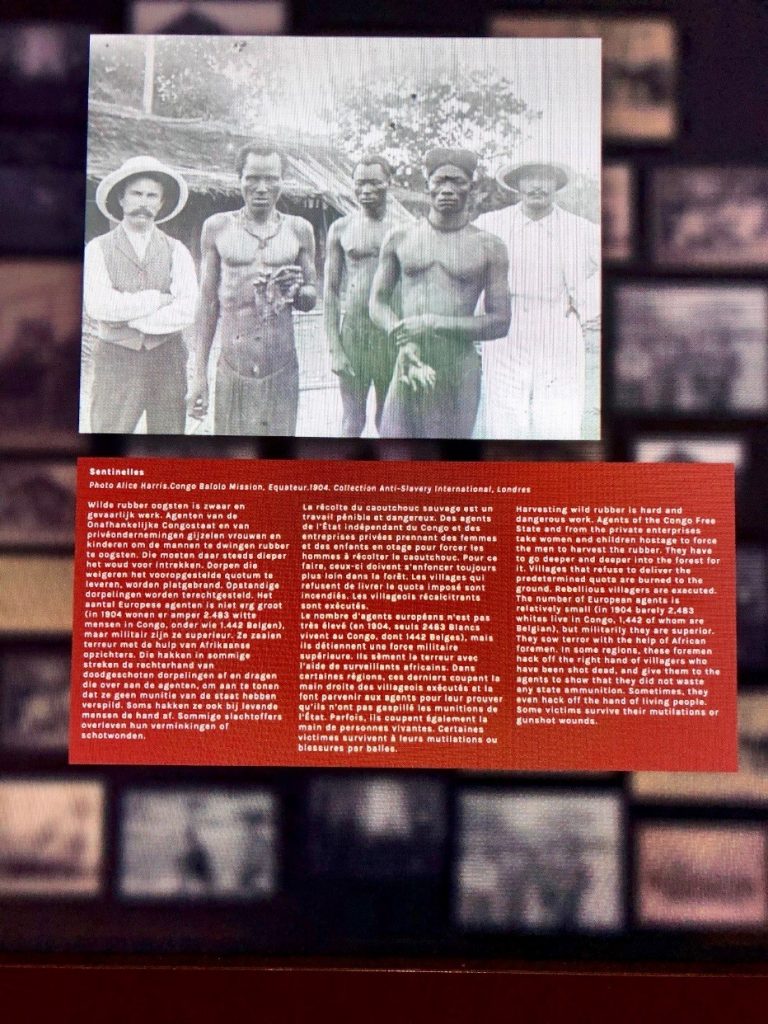

I had been waiting to visit the now rebranded Africa Museum (formerly the Royal Museum for Central Africa) in Tervuren, just outside Brussels, for a long time. The Africa Museum is the largest single collection of objects, artefacts and archives relating to Central Africa (Congo, Rwanda and Burundi) anywhere in the world, with over 10 million zoological specimens, 170,000 photos, 120,000 ethnographic items, 8,000 musical instruments and some 3 kilometres of historical archives; only 1% of the collection is on permanent display. Initially conceived as a propaganda exercise for the Brussels International Exposition of 1897, the museum moved to its grandiose, purpose built palace (modelled on the Petit Palais in Paris) in 1910.

The collection represents in material form, the staggering acquisitiveness of high 19th century European colonialism: the stolen natural and manmade treasures of Central Africa on display at the heart of Europe, a display that has been called ‘a monument to the worst excesses of European plunder’. Even more disturbingly, during the Belgian colonial period, human exhibits were a standard feature of the museum; Congolese men and women brought to ‘animate’ the collections during colonial expositions lie buried in unmarked graves in its grounds.

Over the course of the last decade the museum has been the subject of an extensive refurbishment, opening on 8 December 2018 after a five year period of closure. The refurbishment (and indeed, the reimagining) of the museum was long overdue; the Royal Museum of Central Africa had become an embarrassingly large colonial relic.

[Image 2: gilded statue of King Leopold II inside the Africa Museum]

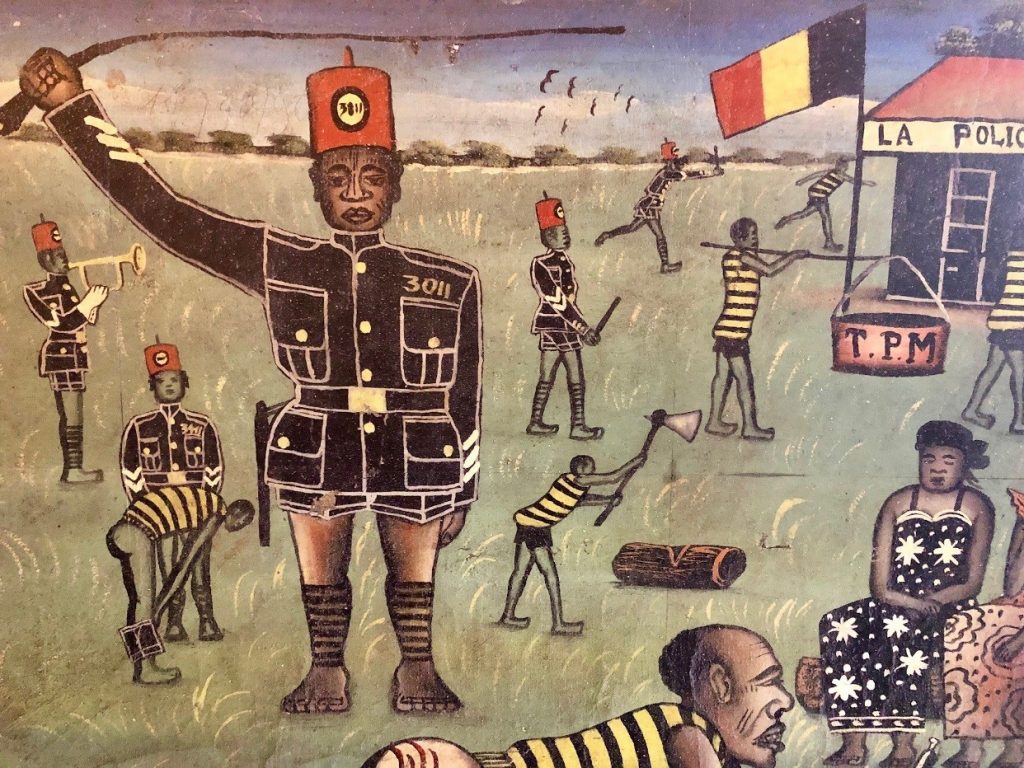

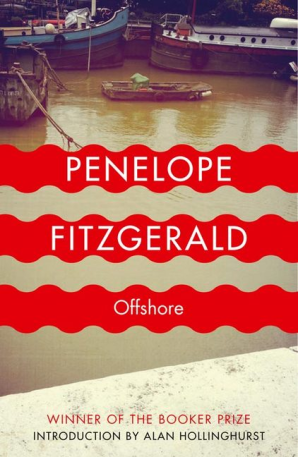

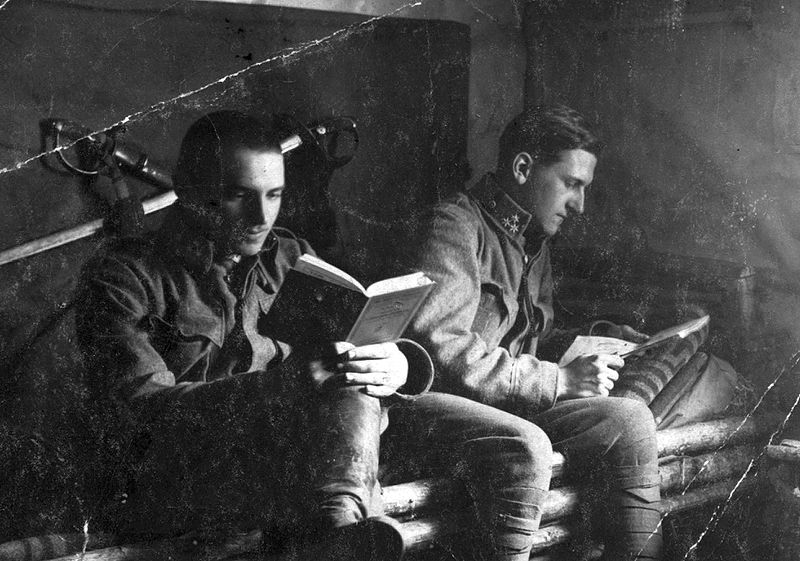

Nothing can disguise the naked paternalism and casual assumption of racial superiority at the heart of King Leopold’s venture, demonstrated most viscerally in the gilded statutes of the Belgian monarch engaged in the civilising mission that dot the marble clad interior of this palace museum. But the refurbished museum is now making a start at acknowledging some of the unpalatable truths from which visitors had been shielded for over a century. As Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost (1998) has shown a century after Conrad, the sheer brutality of forced labour in the Belgian Congo resulted in the deaths of over 10 million people and has been called a ‘hidden holocaust’. The Africa Museum now features a new educational centre and information that begins the conversation about how an archive such as this, constructed as an unrepentant celebration of imperialism, can be used to interrogate and confront in the past – and be of relevance to new, multicultural generations growing up in Europe’s political capital.

[Image 3: forced labour in the Congo Free State, c.1904 – on display in the Africa Museum]

So, why should any of this matter to us today? Conrad’s writing on colonial atrocities in Africa in Heart of Darkness had a clear impact in terms of shaping my early literary interests, and proved pivotal in my choice of subject to study at university; eventually, this led to a career as an academic in English Literature. Likewise, visiting the newly reopened Africa Museum after a lengthy period of closure represented the fulfilment of a personal wish; but curiously enough, there is also a particular relevance to my own practice as a researcher which I should like to reflect upon, something it is relevant to anyone researching in the humanities and social sciences today.

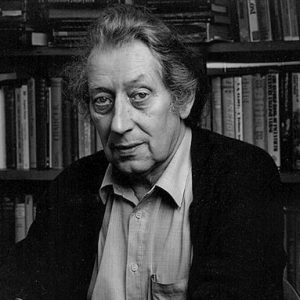

Academic research (like the rest of life) does not exist in a vacuum, but is always shaped by historical, political and economic forces. I have recently been awarded a British Academy/Leverhulme Small Research Grant to support my research. I am of course, delighted to be the recipient of this prestigious small grant, which will allow me to develop over the course of two years (October 2018-October 2020) a current research interest of mine, the reading (and engagement with reading cultures) of the explorer and travel writer, Dame Freya Stark (1893-1993) . Like almost all funding councils, the British Academy is bound by a code of ethical standards and is committed to supporting excellence in research; it really is as it claims, a ‘voice that champions the humanities and social sciences’. But where did the money for my research project actually come from?

The Small Research Grant scheme is funded in partnership with the Leverhulme Trust; founded in 1925 as a bequest by the industrialist William Hesketh Lever, 1st Viscount Leverhulme (1856-1925), this registered charitable trust provides annual research funding of over £80 million. Leverhulme, like Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902) whose tainted legacy is now the focus of the ‘Rhodes must fall’ campaign, was both an extraordinary philanthropist, and a ruthless imperialist. Leverhulme’s business empire (Unilever) was substantially based on the exploitation of African land, labour, and raw materials. As the historian Jules Marchal has demonstrated in Lord Leverhulme’s Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo, Lord Leverhulme was a personal friend of King Leopold of Belgium and an unapologetic supporter of imperialism in Africa. Unilever massively depended upon forced labour in Congolese plantations for its guaranteed supply of palm oil for the production of soap (this practice continued uninterrupted until Congolese independence in 1960). Incidentally, the British Academy was first proposed in 1899, the same year in which Conrad’s Heart of Darkness was first serialised in the pages of Blackwood’s Magazine; it received its Royal Charter from King Edward VII in 1902, the year in which Conrad’s novella was published in volume form, and is currently based at Number 11, Carlton House Terrace, which from 1856 to 1874 was the home of W.E. Gladstone, Prime Minister at the time of the Berlin Conference (1884-1885) that formalised the European colonial carve-up of Africa (and confirmed King Leopold’s personal fiefdom of the Congo Free State).

[Image 4: forced labour during the Belgian colonial period. Africa Museum]

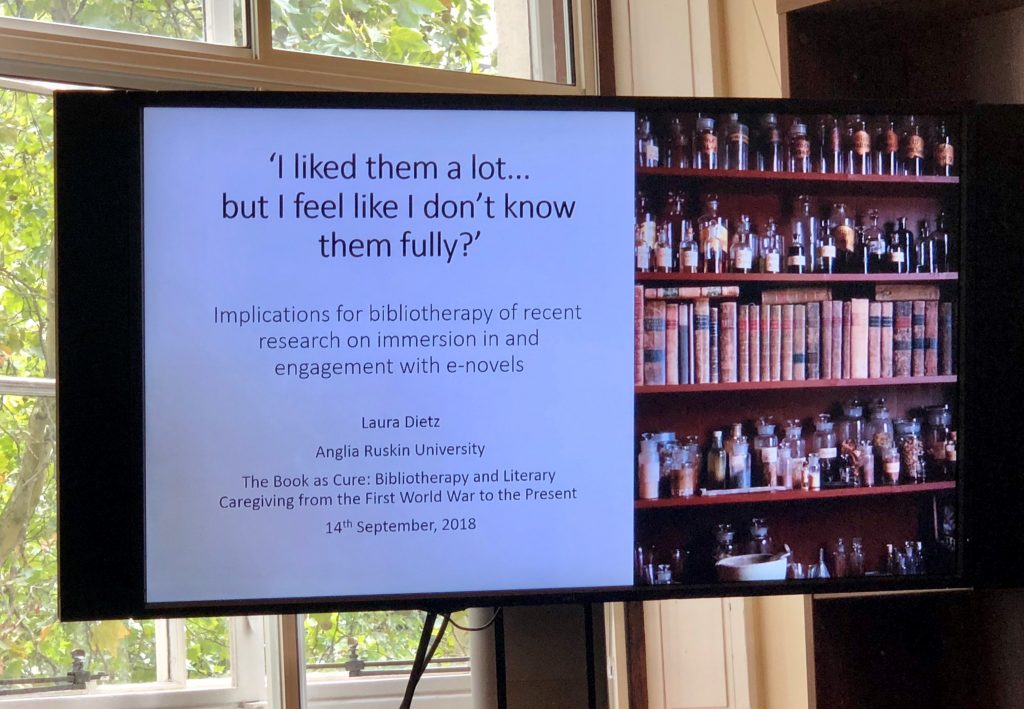

As the motto in the welcome hall of the Africa Museum reminds us, ’everything passes, except the past’. This first admission of the brutality of the colonial past means that the decolonisation of the Africa Museum has only really started in 2018, and may take some decades to reach fruition. Sadly, the exploitation of Congo’s natural resources by corporate and neo-colonial external powers with the connivance of successive regimes, exemplified in the 30 December 2018 elections, continues to this day. A century ago, it was rubber, timber, ivory and palm-oil; today, it is gold, diamonds, and especially columbite-tantalite (coltan) ore to extract tantalum, the metal that powers the smart phones of the world.

[Image 5: welcome hall, Africa Museum]

We cannot change the past – but we all have a duty to acknowledge its pervasive influence on us today, for we are all, whether we like it or not, the products of European imperialism and colonialism. My visit to the newly refurbished Africa Museum as a grant holder of money, derived in part from the forced exploitation of Congolese labour, provided a salutary reminder about the personal responsibility we all bear in terms of ethical research: we must conduct our research in accordance with the ethical guidelines of funding councils, but also, and more importantly, openly acknowledge the source of that funding and the human exploitation and misery that created it. To do any less, would be to dishonour the countless victims of imperial exploitation, and be a grave disservice to ethical research.

Notes

The Africa Museum reopened to the public on 9 December 2018. It is open for visitors everyday apart from Mondays and the standard closure dates of 1 January, 1 May and 25 December. Shafquat Towheed is a Senior Lecturer in English at The Open University, and visited the museum on 18 December 2018.