By Helen Owton and Gavin Williams

Many students find referencing confusing and it seems that confusion comes from not fully understanding what is meant by voicing your own opinion in the context of an academic essay. Indeed, you are asked to write about what others have found and argued yet at the same time, you are told that you need to think for yourselves and come up with your own ideas and interpretations. According to Norton et al. (2009), those who are skilled essay writers respond to the essay by:

- Reading the relevant sources

- Formulating an argument that represents their personal stance

- Ensuring that all the points they make in their essays are supported with evidence from the literature

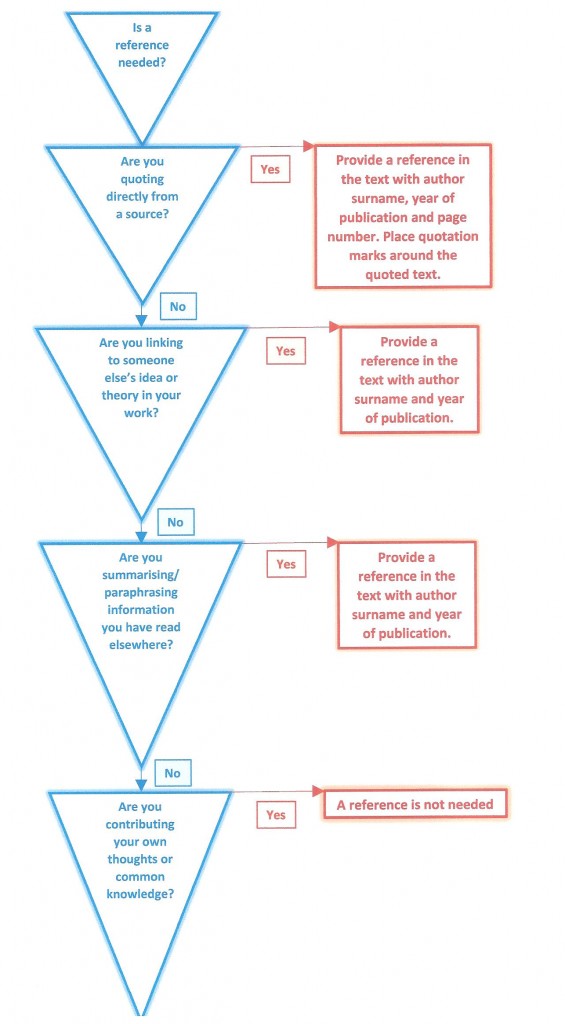

Knowing when to reference and the specific conventions required can prove difficult, however, particularly for students new to studying at university level. The flowchart below “Is a reference needed?” provides some useful guidance for you:

As the diagram points out, you cannot make claims about knowledge in your essays without backing up with reference to the appropriate sources. It is the same with concepts and ideas. It might help to think about your own experiences; for example, think about how annoying you might find someone passing off one of your ideas in a meeting as their own without mentioning that the original idea came from you. As Jill, a student (cited in Norton et al., 2009, p. 79) points out “You can’t just make a point and leave it at that, you need to show the evidence is out there. This has been said and it is in this journal or this book” At undergraduate level, most points and ideas should be referenced, therefore, search through relevant journals and find previous research in order to support your points. First and foremost, you should use the module materials in order to show your understanding of what you have studied. As you increase through the levels (e.g. level 3), you might start to use other different sources of information as listed below:

- Journals: the quantity and quality of your evidence will increase greatly and so will your topic of the area

- Textbooks e.g. the Study Guide or Reader for your module(s).

- Other credible documents

In E217 Sport and Conditioning Science into Practice, for example, you are encouraged to explore sources outside the module material to produce a “Personal Investigation”. Not only must you cite where you found ideas or knowledge, you must do this accurately as referencing is essential in higher education. You must do this in 2 ways:

- In the text, by putting in brackets the author’s surname (not their initials) and the date when the study/book was published

- And in the referencing section at the end of your essay, by alphabetically listing, by author, all journals, books, websites and other sources you referred to in the main text of your essay

Additionally, in sport, the general rule of thumb is to avoid using too many quotes because summarising information helps you understand something better as well as demonstrate your understanding to the person reading your work. Including too many quotes can result in a very superficial response to a question and when you are being marked you are not demonstrating your understanding to the reader/tutor. You should therefore keep direct quotes to a minimum and look to summarise (paraphrase) the information you have read whenever possible. Despite the need for referencing and citing appropriately, you must write about it in your own words. This can help demonstrate your understanding of what you have read and that you can apply this understanding to the question you are attempting to answer. Remember to reference it in the text AND in the reference list at the end of the essay. By doing this you are meeting academic criteria.

Getting penalised

It is important to get your head round referencing because a lack of referencing can directly affect the overall quality of your response to a question and consequently affect how tutors mark the essays. Many tutors take the view that when students have been told how to do something in their writing and then do not do it, it is valid to penalise them by lowering their mark (Norton et al., 2009). This happens particularly when a student’s turnitin scores are high (e.g. over 25%) which shows a high level of copying directly from another source or putting things in your own words.

In order to gain further information about referencing on your module take a look at the Assessment Guide, available from the module website. The Open University library provides a range of resources to assist with academic writing and referencing. The Referencing and Plagiarism section here contains further information along with a very useful video about plagiarism. In addition, the Study Skills section on your StudentHome page also contains some very useful resources to help you plan and write assignments. Remember too that your tutor is there to provide support so do get in contact with them if you would like some specific advice about referencing.

In essence, “Every single name that appears in anything you write must be followed by a date in brackets, and the full reference must be presented at the end of your assignment” (Norton et al., 2009, p. 83). These cited references should then be listed at then end of your assignment in a reference list.

Reference List

Norton, L., and Pitt, E. with Harrington, K., Elander, J. and Reddy, P. (2009). Writing Essays at University: A Guide for Students by Students. London: London Metropolitan University, Write now Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning.