By Leslie Budd, The Open University Business School

The start of the football World Cup 2014 in Brazil has heightened the senses about the world’s most popular sport: the beautiful game. Its appeal is global, primeval and visceral that brings out soliloquies from Existential philosophers among many others. The Algerian-French Albert Camus wrote:

“Everything I know about morality and the obligations of men, I owe it to football”

whilst his famous Parisian counter-part Jean-Paul Sartre stated:

“In football everything is complicated by the presence of the opposite team.”

In spite of these affirmations, the beauty of skill and movement of the game hides a number of very deep flaws. In particular how football has become a global business and brand that operates at a number of levels.

The organisation responsible for global football is Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), that has overseen the global reach of the game spread further and resulting in the current World Cup being viewed by 3.7 billion people. Football accounts for $200bn of the total revenues of $450bn generated by sport globally in 2013, Europe’s share is 10% of this and for the 2012-13 season thoe English Premier League scored the highest with $4.23bn. The main drivers of these revenues are gate receipts, media rights (including advertising) and sponsorship.

Yet, FIFA as the global organising body and football in general are in a paradoxical position. FIFA has been bedevilled by examples of corruption with a strong suggestion and supporting evidence that this is more than a ‘few bad apples’. As for football overall, Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski note in their book Soccernomics, that football is the “Worst Business in the World” populated by bad staff. Clearly the issue of corporate governance is something that will not go away, despite football’s often blithe ignorance of its centrality to running any business, whether privately owned or publicly quoted. In the past, many British clubs thought becoming a quoted company was a one-way street to riches; they became disabused of this fantasy as the teeth of corporate governance bit hard.

Although a number of clubs seek to reach out to local communities the strong impression is given that the employment of ex-players as TV commentators is a “care in the community scheme”: inward looking, living in the past and in the main unaware of a wider world. This is a limited example of ‘trickle-down’ economics that football organisations appear to be the last exponents of. This is especially so in the lead-up to World Cup competitions in which the very large expenditures on stadia and associated infrastructure are justified on the basis of “legacy”. The driver for many of these global events, however, is political: Hitler failing to justify his theories of race in 1936 Olympics. Similarly, Argentina’s military regime used the 1978 World Cup to legitimise its position, and so on. In the case of the awarding of the 2022 competition to Qatar, it is considered a project of modernisation despite the antediluvian and harsh labour practices for immigrant workers; the question of corruption notwithstanding.

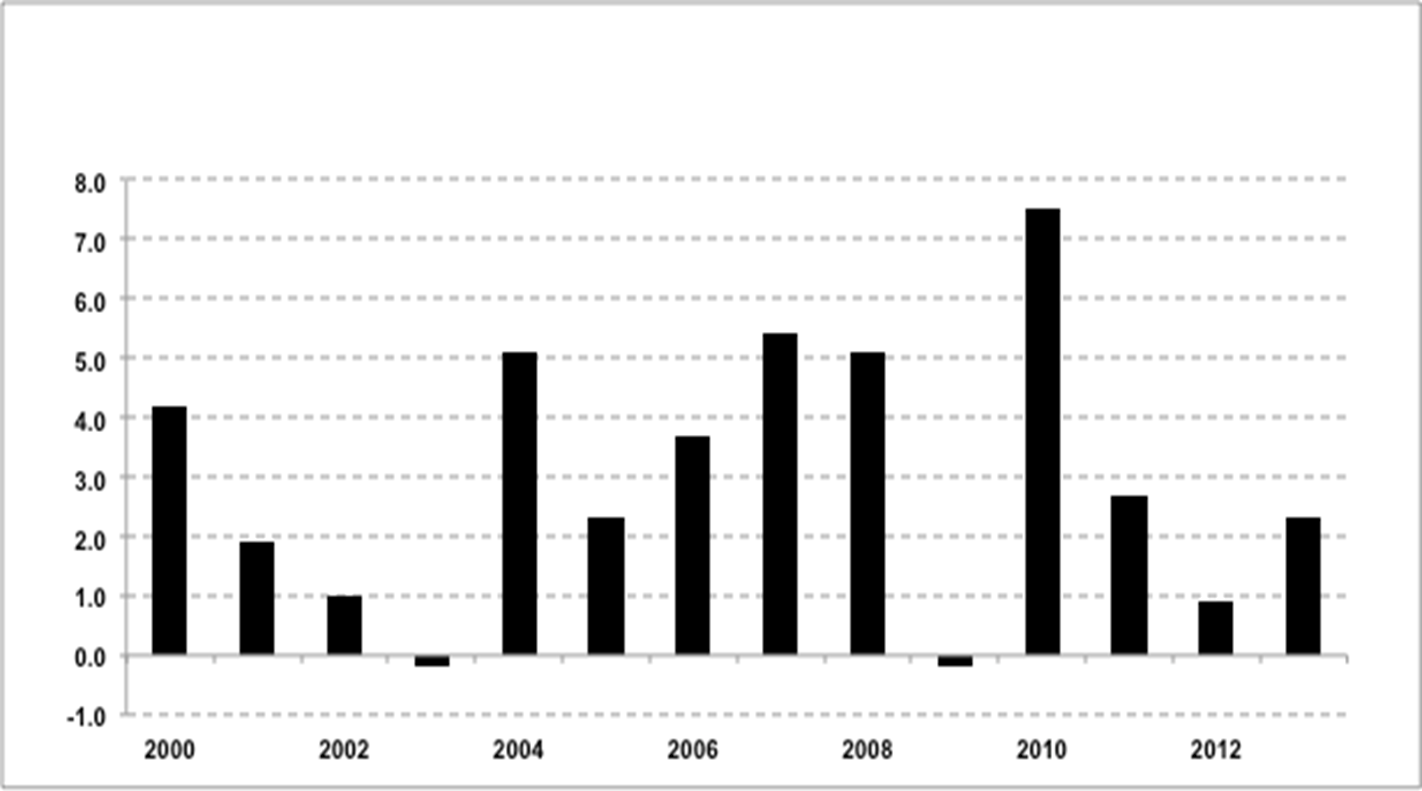

In the case of Brazil, the competition has been sold on the vibrancy of its society and people with its football representing the pinnacle of style and grace. But underneath the ‘Samba Beat’ is a complex society and economy with extremes of wealth and poverty, urban violence public corruption. Political protests and strikes by public sector workers occurred at the start of the tournament as manifestations of deeper ongoing problems. As one of the emerging economies known as BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China), Brazil was lionised as an epitome of this new breed of economy. Yet it has suffered the curse of being a commodity economy (a large exporter of foodstuffs , oil and metals) with its growth rates tending to match the volatility in commodity prices (that boomed at the end of the last decade and are now in decline). The annual growth rate between 2000 and 2013 is shown below:

Furthermore, the boom in commodities boosted the local currency (the Real) so that other economic activities have become internationally uncompetitive. In such an uncertain economic environment, building expensive “cathedrals in the desert” for the World Cup only benefits a limited section of the population. What trickle down there is only represents a few drops of relief in this vast country.

But now that the tournament has kicked off most of us who are fixated on football will turn a blind eye to these distractions. Yet they reflect on the general game of business that is too often played like World Cup football: winner takes all. Failures of corporate governance, tax avoidance by global companies and the perpetuation of an overpaid corporate elite have continued despite attempts to regulate business and finance rather better following the global crisis. The root of the failure of the global economy to sufficiently recover and rebalance has been the lack of commitment to play the equity game, as noted by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) among others.

There are new models of business for football that business in general could learn from. These include self-funding community engagement models in which clubs are community assets or in the case of Germany effectively social enterprises. This approach has so far eluded the elite clubs and when faced with question of probity, FIFA resorts to appeals to the post-colonial race card to perpetuate its hold on the global game. Like the moral of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray in which the main character sells his soul to preserve his eternal youth but his portrait ages, the beautiful game suffers the effects of the underlying deterioration of its global reputation.

Still when Argentina win this tournament the team will dedicate it to liberating Las Malvinas (the Falklands). Sadly, the business of football and the football of business will go on as before. We should all do something to change it.