By Ben Oakley (The Open University) and Steve Mitchell (Sporting People)

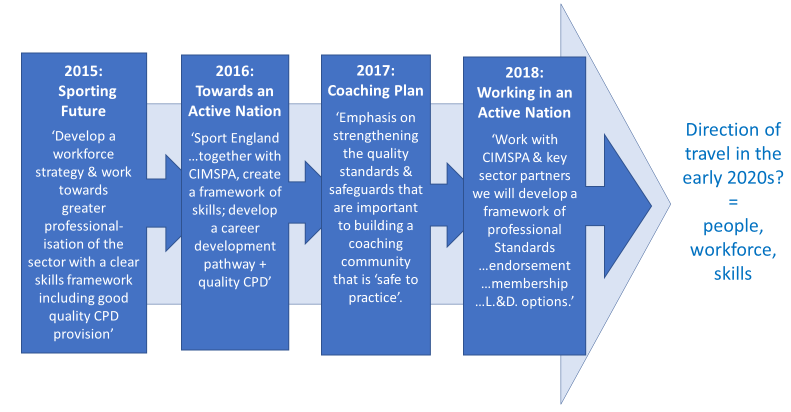

Central government (2015) and Sport England (2016, 2017 and 2018) have both indicated their desire to see more focus and funding invested into developing the sport and physical activity workforce. But what does this mean for your organisation and the people you employ now and in the future? This is particularly important if you are a public organisation or a club that is interested in receiving taxpayers’ or National Lottery funding beyond 2020. In this article we illustrate four examples of workforce development in action and consider what further transformation might look like. But first: why is change needed?

Figure 1 A timeline of main strategy announcements from Government (2015) and Sport England (2016-2018) indicating a direction of travel for policy and funding.

Why change?

Approximately 900,000 people are paid, many part-time, in supporting, or coaching, others in sport or physical activities (Sport England, 2018). They represent, in effect, a significant social movement. Yet, research suggests their approach to working with marginalised groups, and engaging inactive communities is often sub-optimal (e.g. London Sport, 2017).

The training of this workforce is also inconsistently delivered, assessed and benchmarked against other professions and regulated sectors. The CEO of Sport England suggests that claims about inactive groups being ‘hard to reach’ is unjust; the current approach of organisations to engage many inactive or marginalised communities has been poorly informed and executed.

Therefore, if we all agree to:

a) increase the number of physically active people we need to better prepare our ‘people’ by developing them with the skills and confidence to work towards this.

b) And, in order to maintain the confidence of the general public, and for the public health, justice and education sectors to invest in our work, we need to change how our learning and development operates. We need to demonstrate that our sector has sufficient quality development experiences to ensure safe practice that is both accessible to all and effective.

Some might say ‘our sport and people are just fine as they are’. Yes, we can continue the status quo but if you value public confidence and funding in our sector then keep reading to see some ideas you should be considering.

Four examples of recent people initiatives

These examples, with online links for further context, have emerged from organisations creating innovative solutions to workforce gaps or needs. To date there has been little coordinated sector effort … but there could be. Do any of these stimulate ideas relevant to your own organisation?

1. A National Governing Body (NGB)

Great Britain and England Hockey has transformed its coach training model to become better at developing appropriately skilled coaches. They have introduced a far wider coach development pathway involving many more specific and online development opportunities and built in more flexible assessment methods to support people to completion. The NGB’s consultation suggested courses “need to have maximum ‘pitch time’ and more online home study opportunities to allow for coaches to learn in their own time.” This has reduced the length and cost of courses, including travel costs.

2. A Community Activator Apprenticeship

Coach Core’s vision is that communities can benefit by having young relatable role models who could progress, not just their own life chances, but improve the lives of others around them too. They create a meaningful education and employment programme for 16-24 year olds funded through the Apprenticeship levy on larger businesses that was introduced in 2017. They focus on young people that need the opportunity the most in deprived inner-city communities and pay a wage during their Apprenticeship. This suggests that coaching related Apprenticeships are a valuable modern training option and pathway into sustainable employment.

3. Quality online coach learning and development

The Open University identified a need for new CPD learning for those that support and develop coaches; very little opportunities currently exist and promotion to the role is currently based on experience, rather than education. Using our expertise in coaching and distance education we launched a free online ‘Coaching others to coach’ course that has attracted 1900 participants in seven months. Learning that is open to all, 24/7, means people can learn at a time that suits them with a quality assured digital badge upon completion. Other CPD opportunities are being explored and the OU have also launched a similar, free ‘Communication and working relationships in sport and fitness’ course.

The Open University identified a need for new CPD learning for those that support and develop coaches; very little opportunities currently exist and promotion to the role is currently based on experience, rather than education. Using our expertise in coaching and distance education we launched a free online ‘Coaching others to coach’ course that has attracted 1900 participants in seven months. Learning that is open to all, 24/7, means people can learn at a time that suits them with a quality assured digital badge upon completion. Other CPD opportunities are being explored and the OU have also launched a similar, free ‘Communication and working relationships in sport and fitness’ course.

4. Active partnership: health professionals and leisure centres

Sport for Confidence programmes place health occupational therapists and specialist coaches into leisure centres, to provide inclusive sporting opportunities to people who face barriers to taking part. For instance, those with learning disabilities, mental health issues, dementia, autism or disability. The model works by using mainstream environments and delivery adjustments alongside breaking down barriers to ensure sport and physical activity is more accessible and can deliver occupational outcomes for public health and social care.

Final thoughts

Momentum is building with the Chartered Institute for the sector (CIMSPA) and UK Coaching refreshing quality standards for the sector and developing products to support coach development. In the future you need to be actively investing in your workforce, more so than at present. Perhaps it is timely to start to think about creating a ‘people developer’ role to prepare for the challenges ahead. But, for us, this far more than a coach education lead or HR specialist. How will these people developers be prepared for their important new role? Who has the insight on recruiting this talent and ensuring it is ready for the challenge?

We await feedback on this post and if there is interest, we may continue to write more on this intriguing topic. We think it is a puzzle to be solved in several ways.

References

London Sport, (2017) Bigger and Better Workforce Review, August 2017. Available from: https://data.londonsport.org/dataset/vdkjm/bigger-and-better-workforce-review.

Sport England, (2017) Working in an Active Nation: a Professional Workforce Strategy for England. Available from: https://sportengland-production-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/working-in-an-active-nation-10-1.pdf

The Authors

Ben Oakley and OU colleagues, have developed online CPD provision for those who develop coaches along with resources for other groups.

Steve Mitchell sits on an Active Partnership board and holds various Directorships across skills and training.