** This post was originally published on the Ed Studies (Primary) webpage on Friday 4th December**

As a Sport Studies student you are familiar with being asked your opinion, possibly connected to module experience or maybe responding to a survey about a new initiative. This culminates in the final year of under-graduate study when in the Spring the National Student Survey (NSS) consultation is conducted. The NSS collates students view with an aim to improve the overall student experience and its powerful results are openly published.

As a Sport Studies student you are familiar with being asked your opinion, possibly connected to module experience or maybe responding to a survey about a new initiative. This culminates in the final year of under-graduate study when in the Spring the National Student Survey (NSS) consultation is conducted. The NSS collates students view with an aim to improve the overall student experience and its powerful results are openly published.

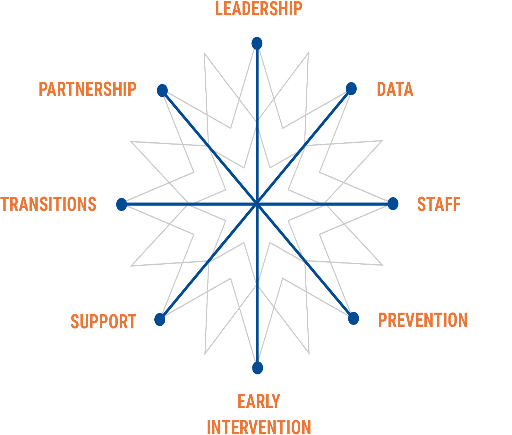

On a different subject – or is it? – levels of poor mental health and low wellbeing amongst Higher Education students are disproportionately high compared to the remainder of the UK adult population, and are increasing (Thorley, 2017). It is no surprise that higher education attainment can be affected by stress, anxiety, depression, grief, sleeping difficulties and relationship problems. Students experiencing these issues report a lower sense of belonging and engagement with their university which can affect retention and progression. In 2017, the #stepchange agenda was launched by Universities UK to improve mental health and wellbeing in universities. The #stepchange framework comprises eight strands which identify the necessary focus for change:

The #stepchange agenda works to increase students sense of belonging and enable students to develop their social identity. This has the potential to improve retention and academic success and ultimately to enhance student experience (Thomas, 2012). In 2020 the #stepchange agenda was developed into a University Mental Health Charter where universities are required to develop a wellbeing strategy (link to OU mental health and wellbeing strategy) and can be nationally recognised for this work.

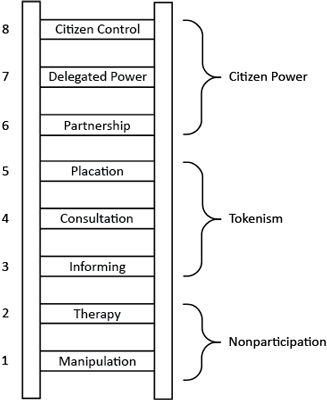

The connectivity between student voice and wellbeing is evident in the way #stepchange is delivered; through co-creation between students and their university. Co-creation is the new buzzword in higher education and requires high levels of student participation, where student voice has the potential to make the most positive impact on student experience. Let’s contextualise our perspective of participation. You might be familiar with Arnstein’s model of participation, where power and control are represented in a hierarchical ladder and students (or citizens in the model) progress to achieve high levels of participation. The highest levels of participation are the hardest to achieve but bear the most fruit in respect of student experience and student success. They cultivate ‘buy in’ from students through authentic collaboration which lower levels of participation such as surveys struggle to achieve.

Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation (1969).

Research with children and young people informs us that a participatory approach to educational relationships produces the best outcomes (Lyndon in Williams-Brown and Mander, 2020). It is the same for higher education students and might be considered more meaningful because study at university is voluntary rather than statutory like school, and we engage in adult: adult relationships where power should be more evenly distributed. In respect of wellbeing, the Universities UK strategy is clear that co-creation opportunities should be available through a whole university approach if student wellbeing is to improve. However, the relinquishing of power can be uncomfortable and impractical. It is best managed as a conscious uncoupling (to use celebrity speak) of the old to introduce the new. It challenges existing, ingrained ways of working within universities, and reshapes the cultural climate which informs our identity as individuals and an institution.

One of the ways in which ECYS are improving student voice and wellbeing is to incorporate a student panel within staff recruitment processes. This happened for the first time in November 2020, with aims for it to be an integral activity in the future. Students who participated said it was a privilege and an honour, planning of activities including a scenario were enjoyable, working as a team was effective, and they felt very well supported and informed about the process. Their wellbeing was enhanced; they reported that being involved was fun and satisfying, it helped to build confidence and they felt valued because their opinion and input mattered. This leaves us wanting more student co-creation opportunities. Can you think of any you would like to be involved in? Let us know, we love to hear about them and promise to respond.

Sarah Mander is a Staff Tutor (line managing Associate Lecturers) and Tutor for E102 module. She is also a serial student, studying for a Doctorate in Education. Sarah leads the ECYS Student Voice and Wellbeing Champions group.

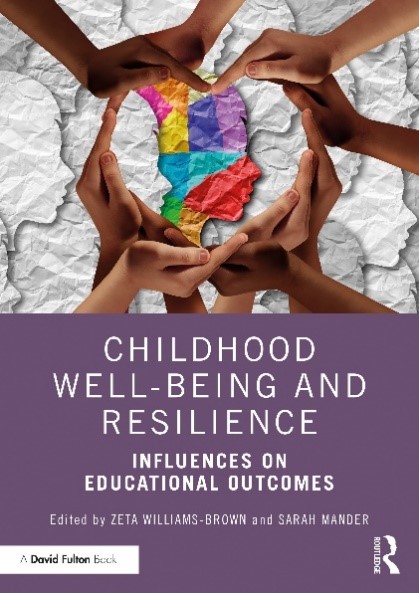

Sarah has researched and written about wellbeing, mental health and the student population for the publication Childhood Well-being and Resilience: influences on educational outcomes (Williams- Brown, Z. and Mander, S.Eds., 2020).

References

Lyndon, H. (2020) ‘Listening to children the rights of the child’ In, Williams- Brown, Z. and Mander, S.Eds. ‘Childhood Well-being and Resilience: influences on educational outcomes’. Abingdon: Routledge.

Thomas, L. (2012) Building student engagement and belonging in higher education at a time of change[online]. [accessed 7 January 2020].

Thorley, C. (2017) Not by degrees: Improving student mental health in the UK’s universities. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Universities UK (2017) #stepchange mental health in higher education [online]. http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/stepchange/Pages/default.aspx [accessed 10 January 2020].