by Ben Langdown

As I returned home from my run last night, I was saddened to receive the news that Dr Ron Hill MBE had passed away at the age of 82. For those of you who may not be familiar with his name, Ron was a British athlete who, in 1970 at the age of 31, won the Boston Marathon in a, then, record time of 2:10:30 hours, breaking the previous time by 3 minutes. Later that year he went on to win Commonwealth gold in the marathon in 2:09:28 hours. This was not the first time Ron had recorded a sub 2 hour 10 minute marathon – in 1969 he was the second man ever to break that time barrier. Furthermore, Ron broke four world records in various events and ran in 115 marathons in 100 different countries. These were, and still are, impressive achievements, with Ron’s Commonwealth finishing time currently ranked as the 12th fastest time by any Briton.

However, for me, what is even more inspirational is the fact that, from 20 December 1964 to 30 January 2017, Ron Hill ran a minimum of a mile (averaging 7 miles) every single day for 19,032 consecutive days – that’s a streak of 52 years and 39 days! He did this whatever the weather, and despite suffering with illness and injury – such as flu, and even cancer surgery. A head on car crash in 1993 saw Ron being diagnosed with a broken sternum and lucky to be alive. Fortunately for his streak, he had already run that day, but the next day had to sneak out for a slow, flat mile when his wife popped out to do the weekly shopping! He only dared tell her a week later! In the same year, he had to adapt one of his trainers in order to accommodate a plaster cast on his foot following a bunion operation – this allowed his streak to continue as he managed a mile every day for the six weeks, post-op.

Why is this so inspirational to me? Because, I found out about Ron Hill during my attempt at a new year’s resolution in 2017. A friend had completed a year of running a minimum of a mile every day and I had decided to give it a go. They’d said the first 100 days were the hardest, and they weren’t wrong. Starting a challenge like this in the miserable, damp, cold, dark days of January and into February was not conducive to completing the challenge. However, I ran on through those and completed the year, and now 4 years later I am on day 1606 of my own running streak.

Day 1500: A 7km headtorch run in the snow – Not how I imagined celebrating that milestone!

Like Ron, I have had my own challenges in completing a minimum of a mile on some days. Yes, the occasional illness has made it hard, sneaking out when my wife has popped out leaving me with strict orders to rest. Realising, on another occasion at 11pm while lying in bed, that I hadn’t run that day and going downstairs to complete hundreds of shuttle runs back and forth through the open kitchen and living room doors – just to clock up a mile on my watch! And running at 10.30pm on a full belly of curry, naan bread and a couple of pints after forgetting to run before a meal out with colleagues…needless to say, there have been some slower miles mixed in along the way.

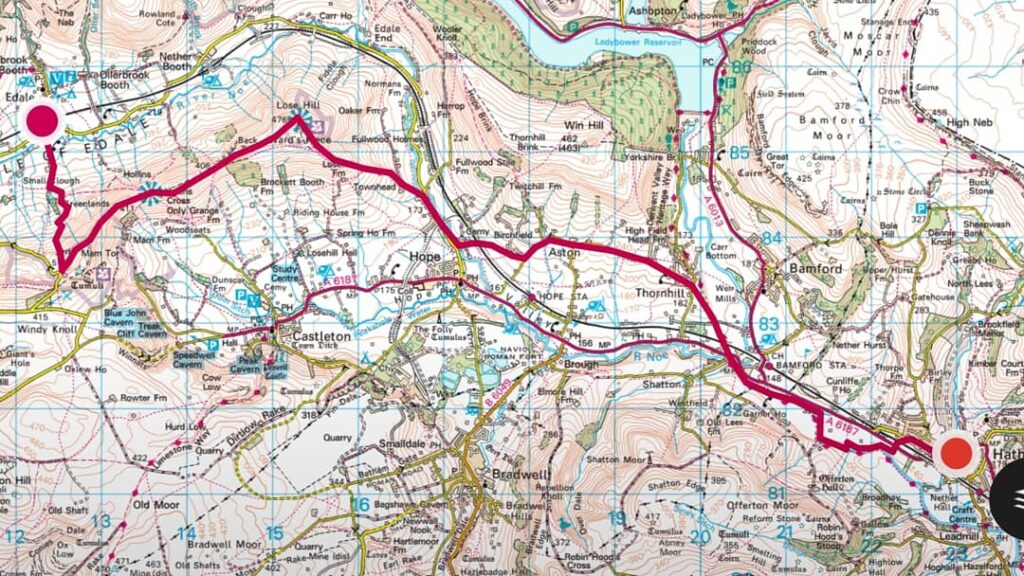

Day 1000: A celebratory 17km trail run in the Peak District

There have also been many highlights and benefits of committing to running every day. My fitness has improved, I’ve explored so much more countryside (including in Italy, Canada, USA and across the UK), seen stunning sunsets…

Sunsets on day 1408 and 1542

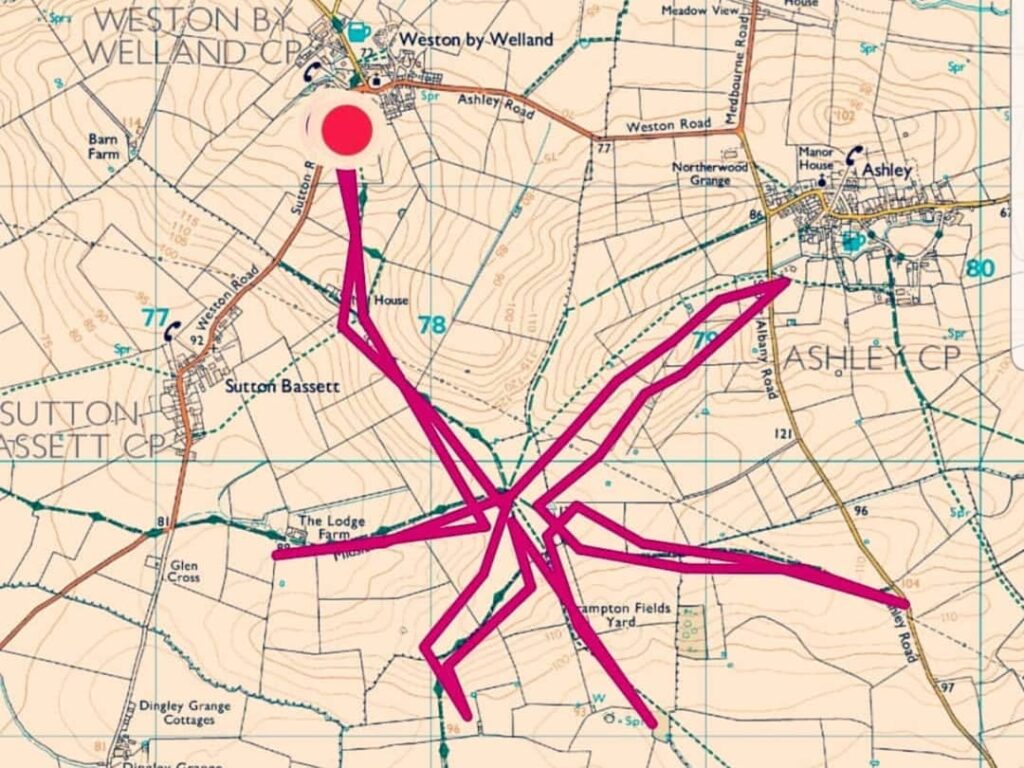

…desk breaks now have a renewed purpose, I’ve run new road routes, trail routes, up and down beaches, enjoyed being with friends, travelled to the Peak District to run up Mam Tor (title image) and along the Great Ridge on day 1000, drawn fancy GPS maps (e.g. shooting star!), clocked up personal bests and set new challenges along the way. This year I am attempting a minimum of 5km a day, spurred on by all the geeky data a new GPS watch has brought to me and the monthly competition with friends on total distance achieved! 566 miles (906 km) so far this year and I’m yet to get out and run today…

Day 958: Shooting Star: A 14km run with Dr Nathan Smith in the Leicestershire countryside

I’m still way off Ron Hill’s >52 year streak, and having started mine at the age of 37 I was 11 years older than he was on his first day. I know this means I may never get close to his streak and indeed I am not sure where or when mine may end, but despite all this, I am enjoying the challenge and am still greatly inspired by the British running legend, Dr Ron Hill MBE.

Run 1606 – for Ron

#runeveryday

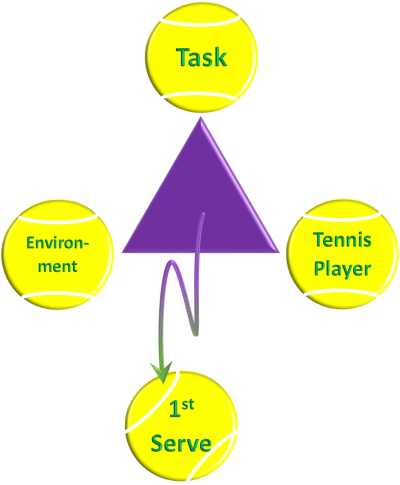

Welcome to the support blog for the E236 WebApp. The following screencast will take you through the key features of the WebApp allowing you to apply your professional knowledge from Study Topic 4 (as well as the preceding Study Topics). If, once you have watched the screencast fully, you have any further questions, please comment below or post in your Tutor Group Forum for you tutor to liaise with the central module team.

Welcome to the support blog for the E236 WebApp. The following screencast will take you through the key features of the WebApp allowing you to apply your professional knowledge from Study Topic 4 (as well as the preceding Study Topics). If, once you have watched the screencast fully, you have any further questions, please comment below or post in your Tutor Group Forum for you tutor to liaise with the central module team.