By Simon Rea

Firstly, welcome to The Open University and secondly, thank you for choosing to study on the sport, fitness, and coaching degree. We have a range of fantastic courses for you to study to support you towards achieving a fulfilling career working in sport or fitness. During this turbulent year of 2020 it seems to me that sport has become even more important. Research has shown that fit and healthy people are less affected by Covid-19 and as a result we have been encouraged to take daily exercise outdoors, and the fitness industry has seen a surge in people engaging with online fitness platforms. During this time I felt lost when there was no live sport for three months and like many others have binged on sport since its return.

As a sport and fitness student it is likely that you feel as passionate about sport and fitness as I do and in this blog I want to encourage you to make the most of your undergraduate studies. I want you to get the best value for the personal and financial investment you have undertaken and the sacrifices you may have to make. While sport and fitness offer a range of exciting careers and the opportunity to work with interesting and inspiring people the job market is highly competitive. Sport science, studies and sports coaching courses are now the most popular degree course in the UK with around 15,000 graduates a year leaving around 138 universities that offer these degrees. Indeed there are almost 1500 students enrolling, along with yourself, on year 1 sport and fitness modules at The Open University.

Therefore, it is advantageous to get ahead of this competition and give yourself as great an advantage for the future as you can. We appreciate that you have busy lives and finding time to study may not always be easy as you juggle work, family, and social commitments. These conflicting priorities can lead to students being tactical in how they study. To encourage you to make the absolute most of your time spent studying with us and to maximise your learning and enjoyment I will offer three pieces of advice for you to consider whilst studying.

- Engage with all the resources available to you and read as much as you can.

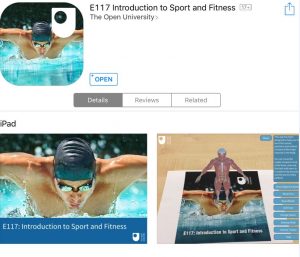

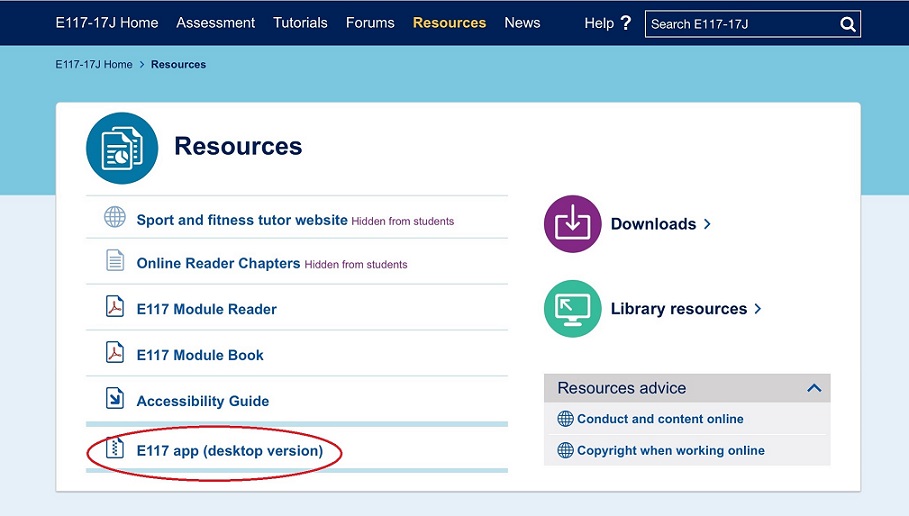

In your module materials you will find a range of resources. There are readings, audio and video clips to watch and listen to, websites to visit and activities to complete. We will also offer additional resources at certain points so that you can find out more. We would encourage you to learn as much as you can about the subjects you are studying by reading widely and visiting websites related to the subject. Social media offers a plethora of opportunities and you can follow experts and influencers that you are interested in. For example, Twitter enables you to follow coaches, personal trainers, and academics in sport.

- Engage with your tutor and your fellow students as much as possible.

Before you start your module you will be assigned a tutor and a tutor group. Your tutor will tell you how to contact them and you will be given information about the schedule of tutorials. You will also find out about your online tutor group forum where you can meet and interact with other students.

This engagement with other people is crucial to your understanding of the module materials as some of the most valuable learning is described as social learning where you learn from other people. Discussing and debating can give you different perspectives on a subject and hearing other student’s experiences can broaden your own understanding. This kind of learning will happen during tutorials and during collaborative tutor group forum activities. During the learning process it is vital that you do not accept all content without questioning it. Ask yourself – ‘where did this knowledge come from?’ ‘Are there other ways of doing things?’

Discussing, debating, and questioning will improve your understanding of a subject but it will also develop critical skills that are so crucial in higher education and valued by employers.

- Always keep in mind the question ‘How does this relate to me?’

While knowledge is exciting to have it is most valuable when you can actually apply it. This may be applying it to your own working practice or to help yourself and other people. So, you must always find opportunities to apply your knowledge. This may be reflecting on past experiences and gaining new perspectives on them or thinking about how you can use the knowledge now or in the future.

I have always found that when people know I am involved in sport science they have questions about their training or their diet. Let people know you are studying sport and fitness and talk to them about it and express your views if the opportunity arises. Sharing your knowledge with other people is a great way to increase your own knowledge and understanding of a subject.

Final thoughts

As I said earlier we appreciate that studying is just one factor amongst many competing for your time and it may be difficult to implement all three pieces of advice consistently. However, if you bear them in mind during your studies you will improve your chances of success both during your studies and in the future.

We hope you have a wonderful experience during your time studying sport, fitness, and coaching at The Open University.

Simon Rea is a Lecturer on the sport and fitness award at The Open University and the author of the books Careers in Sports Science (2019) and Sports Science – a complete introduction (2015).