By Helen Owton & Helen Clegg

“BBC Young Dancer 2015 is a brand new award for young people that showcases the very best of young British dance talent. Young dancers enter in one of four categories of dance: ballet, contemporary, hip hop and South Asian dance. BBC Young Dancer 2015 culminates in a grand final at Sadler’s Wells, when the best dancers in each category will dance against each other for the title.” (BBC website)

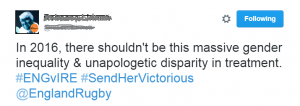

BBC Young Dancer of the Year 2015 was a wonderful showcase of the young talent currently within the dance world. In light of the lack of male representation in dance, The BBC Young Dancer of the Year award seems to have provided boys and men with a platform in which to be valued and recognised. However it also highlighted the gender inequalities in the dance world and suggested that these are reflective of a more pervasive gender imbalance within the workplace. It seems that the BBC have avoided much public scrutiny over the gender imbalance that existed on the programme. Some comments on social media were not happy with this:

“Guess what BBC – we don’t care. First a gender imbalance for the individual finals… Then the judges were mostly male as well, but that’s as per usual. And finally – the only female grand finalist came from an all-female category?! Hate to be a gender-ist, but the female and male bodies as well as personalities make for a different quality in dancing and I would be bored stiff watching an all-male dance performance at any point (this followed by an all-female), a mix is best.”

Whilst there was scrutiny over why particular dance styles were selected over others, and why and how dance styles could be compared to each other, there does not seem to be a discussion about why there was such a lack of female representation on the show. During this discussion we don’t want to take credit away from the boys who made it through to the final, but point out the inequalities that existed from the way the program was set up.

The Judges

Firstly, let’s take a look at the female-male distribution of judges. Only 33% of the judges were female on the shows. Just 30% of leading dance experts was female who selected the grand finalists. For the final, just one female was placed on the judging panel.

Dance is considered a female activity (Risner, 2009) so where are all these women at the top? For example, Arlene Phillips is a world-renowned director and choreographer, who is missing from these panels of experts. The BBC was accused of sexism and ageism when Arlene was taken off the Strictly Come Dancing panel. Indeed, figures show that older women are less likely to appear on TV.

Additionally, why wasn’t Darcey Bussell on one of the judging panels; particularly in the ballet finalist? For Ballet these were the leading panel of experts: Dominic Antonucci, Ballet Master of Birmingham Royal Ballet and Christopher Hampson, Artistic Director of Scottish Ballet with Kenneth Tharp, chief executive of The Place, who judged across all categories.

According to McPherson (2005), “men dominate executive, administrative, and artistic positions of nearly every ballet company in the United States” and women report feeling excluded from informal leadership and decision making networks ringing very true in the world of ballet. Instead of being held up as one of the leading experts in ballet, Darcey Barcell, CBE, former principle dancer of the Royal Ballet at 20years old and widely acclaimed as one of the best British Ballerinas was reduced to being the presenter of the show. Indeed, Williams (1992) argues that subtle forms of workplace discrimination push women out of male dominated occupations that involves decision-making.

With such a high percentage of judges being male, it’s no wonder that just one of the dancers in the final was female out of 6. Not only this, but in each category, there was always a lower percentage of females apart from one category which was all-female:

- Ballet: 40% female

- Contemporary: 40% female

- Hip hop: 40% female

- South Asian: 100% female

However, this is not just a problem with the BBC Young Dancer competition. In 2014, The Young British Dancer awards saw an all-male line up for the six available awards as well.

Possible Explanations

It is well documented that males are the minority in dance education environments (Risner, 2007). Dance in the Western World is generally considered a female activity and so those boys who dance are considered effeminate and often assumed to be homosexual (Polasek & Roper, 2011, Risner, 2014). Risner (2014) has documented widespread verbal, emotional and physical bullying of young male dancers due to these constructions. Thus it is possible that boys who decide to attend dance classes, despite such bullying, are those who are skilled at dance and so the variance in dance ability and passion for dance may have much greater variance for girls than boys with boys being at the top range of the distribution.

Furthermore, within the dance studio environment boys are nurtured and often receive preferential treatment compared to the girls and this may be in part to prevent boys from disengaging (Polasek & Roper, 2011, Risner, 2014). Stinson (2005) talks about how such privilege within, not just the studio, but also the dance world is accepted by both men and women and as such often goes unchallenged. Whilst female dancers are often encouraged to remain passive within the dance class and simply respond to commands, male dancers are often encouraged to participate more fully and challenge the passive position of student dancer as this enables them to reclaim their masculinity (Risner, 2007, Stinson, 2005).

The combination of highly dedicated and skilled males who hold an elite position within the dance class and are encouraged to put themselves forward and challenge the status quo may explain the gender inequality in both the BBC Young Dancer finalists and judges. It is possible that young male dancers were more encouraged by their dance teachers to audition for the competition and were more confident in their abilities to take on such a challenge. This could explain the number of male dancers in the semi-finals since this is a higher proportion of male dancers than female dancers given that male dancers are a minority in the dance world.

The valuing of male dancers, at the cost to female dancers, may also explain the gender inequality in the final contestants. This is not to say that the male dancers did not deserve to be in the semi-finals or finals; far from it. What we want is equally confident and privileged female dancers and a challenge to the inherent gender divisions within dance. Boys also need to know that they are achieving in dance because of their talent and not their gender. Boys need to come to dance unafraid of being bullied and without the fear of having their masculinity and sexuality under scrutiny; Russian boys and men don’t seem to experience this sort of discrimination. Girls need to come to dance knowing they will be as equally valued as boys and have permission to move from passive student to empowered dancer.

Where do we go from here?

Whilst it was a pleasure to watch all the finalists dance, we would like the gender imbalances in dance, for both males and females, to progress in a way that both male and female dancers feel valued for their abilities and skills. So then we are no longer distracted from such talent by the stark gender inequalities presented to us in such programmes as BBC Young Dancer of the Year.

References

Polasek, K.M. & Roper, E.A. (2011). Negotiating the gay malestereotype in ballet and modern dance. Research in Dance Education, 12(2), 173-193

Risner, D. (2007) Rehearsing masculinity: challenging the ‘boy code’ in dance education, Research in Dance Education, 8(2), 139-153

Risner, D. (2014). Bullying victimisation and social support of adolescent male dance students: an analysis of findings. Research in Dance Education, 15(2), 179-201.

Stinson, S.W. (2005). The Hidden Curriculum of Gender in Dance Education. Journal of Dance Education, 5(2), 51-57.

This article was originally published on The Psychology of Women’s Section Blog.

Read the original article here