Many will remember the 2019 Tour de France for its premature finish caused by hailstorms and landslides, rather than the incredible achievements of the endurance athletes. To complete the 21 stages spanning 3,480 kilometres is an extraordinary feat – but what is it about these athletes that allows them to do it? The physiology of a Tour de France rider has been examined in depth by scientists (e.g. Santalla and colleagues in 2012), but in this short article we will be focusing on just one aspect, the heart.

The heart of the matter

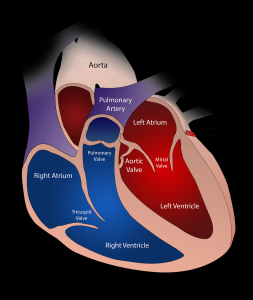

Chris Froome described Egan Bernal, the 2019 Tour champion, as having ‘an amazing engine’  referring to Bernal’s heart, the muscular pump, that drives blood around the body to perform essential functions. Located in the left-hand side of the chest and typically about the size of a clenched fist, Bernal’s heart’s ability to pump the required oxygen to his working muscles to complete the mountain climbs and long distances, is the key to his success.

referring to Bernal’s heart, the muscular pump, that drives blood around the body to perform essential functions. Located in the left-hand side of the chest and typically about the size of a clenched fist, Bernal’s heart’s ability to pump the required oxygen to his working muscles to complete the mountain climbs and long distances, is the key to his success.

We can make such statements because, on examination, as the athlete trains their hearts get bigger and stronger meaning they can pump more blood per beat. Indeed, athletes often have a larger than usual left ventricle, developed through conditioning the body to be as efficient as possible. Referring to these adaptations to training, Bradley Wiggins was described as have a heart ‘like a bucket’ after his 2012 Tour victory.

Because of this increased efficiency, and the trained heart’s ability to pump more blood per beat, a key indicator of an endurance athlete’s heart efficiency is their resting heart rate. Where an average adult’s resting heart rate might be between 60-90 beats per minute (bpm), a Tour de France cyclist can have readings of lower than 40 bpm. Physiological tests carried out on Chris Froome by Team Sky to quash doping allegations after his Tour successes, showed that his resting heart rate dropped as low as 29 bpm.

Cycling is not the only sport that produces these super athletes. Biathlon, combining cross country skiing with precision target shooting, is widely recognised as one of the most challenging winter endurance events. Indeed, the two activities seem unlikely partners with one requiring strength, speed and endurance and the other requiring concentration and a steady hand (while your heart is still thumping from the exertion!).

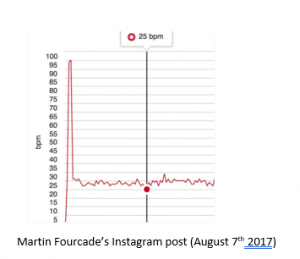

To p French biathlete, Martin Fourcade, winner of over 20 World Championship medals, over 120 World Cup medals and seven Olympic medals posted his own resting heart rate readings on his Instagram account in 2017. He reported an incredible 25 bpm. Although this reading is his own, and biathletes do specifically train to lower their heart beat to enable more accurate shooting, the value is incredible considering the lowest resting heart rate on record is 27 bpm.

p French biathlete, Martin Fourcade, winner of over 20 World Championship medals, over 120 World Cup medals and seven Olympic medals posted his own resting heart rate readings on his Instagram account in 2017. He reported an incredible 25 bpm. Although this reading is his own, and biathletes do specifically train to lower their heart beat to enable more accurate shooting, the value is incredible considering the lowest resting heart rate on record is 27 bpm.

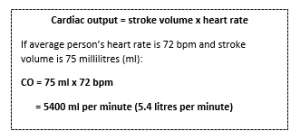

This level of efficiency can also be examined through a second measure: cardiac output – the amount of blood ejected from the left ventricle in one minute. It is calculated by multiplying the person’s heart rate by their stroke volume (amount of blood pumped from the left ventricle in a single heart beat). Therefore, with the trained endurance athlete’s larger left ventricle and lower resting heart rate, they can pump out more blood per beat and their heart needs to beat less frequently to achieve the same cardiac output.

the amount of blood ejected from the left ventricle in one minute. It is calculated by multiplying the person’s heart rate by their stroke volume (amount of blood pumped from the left ventricle in a single heart beat). Therefore, with the trained endurance athlete’s larger left ventricle and lower resting heart rate, they can pump out more blood per beat and their heart needs to beat less frequently to achieve the same cardiac output.

And for those of us who are not elite endurance athletes?

Comfortingly for us mere mortals, and important knowledge for those working in the sport and fitness industry, regular exercise (not necessarily long-distance cycling!) improves heart health and increases cardiac output. This enables us to reduce our resting heart rates and for our bodies to become more efficient, even if not to the extreme levels of the athletes discussed above. So instead of sitting at your desk during your lunch break take a brisk walk, opt for the stairs, and park a few hundred metres further from the supermarket entrance, as these small changes can all improve your heart and most importantly your health.