Authored by the team ‘Is this the way to Amarillo’: Tracie Davies, Fiona Flaherty, Wendy Lampitt, Stephanie Mcilhiney, Lee Nailard, Hayley Slaytor, Guido Volpi, Luke Withey, Kathryn Halley, Paul Maher and Shannon McGovern [E119 20J students]

This blog was written as part of a collaborative teamwork task by students studying E119. They had to select a topic and then decide on what roles each person would perform in the team, such as researcher, writer, editor and leader. This blog was chosen as one of the best blogs from around 80 blogs that were produced.

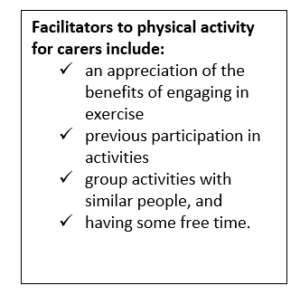

Historically men have been paid more than women in most professions and when it comes to sport, who plays what used to follow gender-based traditions. Perhaps as little as a generation ago these traditions continued to be observed, especially in schools, but as more sports earn greater female representation and more professions bridge the pay gap between the sexes, does that that translate to greater equality of pay for women in professional sport?

Photo by Alex Smith https://unsplash.com/photos/J4yQp1lIJsQ

Female athletes at the Summer Olympic Games now represent almost 50 per cent of all participants (Olympic Games, 2021) but how equally do the more high-profile sports both within and outside the Olympics pay them compared to their male counterparts? Every year, Forbes release a list of the highest paid athletes in the world and in 2020’s list there are only two women in the top 60, Naomi Osaka and Serena Williams (Forbes, 2021). In 2019, only Serena Williams made the list of 100 (Forbes, 2019).

Different sports are governed by different rules surrounding how much their athletes are paid. Since modern tennis was adapted from earlier forms in the mid 19th century (Bustle, 2016), women have participated. The women’s first tennis tournament occurred in 1884, when the first Ladies’ Championships took place at the All England Club at Wimbledon (Wimbledon, 2020), seven years after the first men’s tournament. After 1968, when tennis’ “Open Era” began (Tennis Majors, 2020), Billie Jean King began to campaign for equal prize money for women (Billie Jean King, 2021). In 1973 the US Open was the first Grand Slam tournament to offer it (US Open, 2018) but it wasn’t until 2007 that Wimbledon became the final Grand Slam to join in, one year after the French Open (BBC Sport, 2016).

While tennis has made great strides to achieve equal pay, other sports that have a long history for both genders, basketball and golf, seem to be far behind. Basketball is one of the US’ most popular sports and the disparity between pay for men and women is stark. In 2017 the National Basketball Association’s highest paid player, Stephen Curry, earnt more than £26 million, not including endorsements. Women’s pay for the same year in the Women’s NBA was capped so the highest earning woman, Candace Power, earnt £87,209 (Boost Power, 2021). In golf in 2016 men could win 83 per cent more in winnings than their female equivalent on the golf tour although “They play the same game, to the same level.” (Golf Support, 2016) but although equality seems far off more prize money is being added and the number of tournaments is increasing (Desert Sun, 2021).

Sports such as football (soccer) and rugby which have been considered traditionally male have enjoyed increased participation from women and girls in recent years on national and global levels owing to active campaigns by their governing bodies (Guardian, 2020) (England Rugby, 2019). But while participation may be up, male footballers remain some of the highest paid sportspeople in the world and women receive much more modest salaries, such as in the 2017-18 season where Lionel Messi earnt 130 times as much as the highest paid female footballer, Alex Morgan (Boost Power, 2021). Female rugby players in England have only started to be paid at all since 2019 (Telegraph, 2019) and in the Six Nations competition, while the winning men’s team receive prize money of £5 million, the winning women’s team receives nothing (Luxurious Magazine, 2020).

When drawn on why certain sports are nowhere near awarding equality of pay the same reason is often given: revenue. A great deal of sports’ revenue comes from broadcast rights and to this day there is still vastly more men’s sport broadcasted than women’s sport, leading to far less money in the pot to pay female athletes. A 2017 study by Women in Sport showed that in the UK media coverage of women’s sport accounted for an average of ten per cent of all sport covered, reducing to four per cent at a time when international events had ended (Women in Sport, 2018). The women’s World Cup in 2019 was viewed by 1.12 billion people worldwide, 31 per cent of the number that watched the men’s World Cup in 2018 (Guardian, 2019) but the prize money offered was only 7.5 per cent of that offered to the men’s teams. If viewing figures are a measure of success, even this seems stacked against women’s sport. There are calls for more women’s sport to be available to view (Broadcast Now, 2019) and Sky Sports has run a campaign, “Rise With Us” since March 2020, highlighting women’s sports and plans to expand its existing coverage and digital output (IBC, 2020). If sports’ governance invested more time and money into showcasing women’s teams and players as they have traditionally done with men’s there would be greater awareness, greater spectatorship, higher viewing figures and more revenue.

Photo by Susan Flynn https://unsplash.com/photos/wqaEwf35Bl8

Until this happens there is, however, some hope. Relatively new sports such as triathlon and the more recently founded CrossFit offer equal prize money for male and female competitors and have done since the outset (BoxRox, 2020; World Triathlon, 2016). Both describe this stance as an inherent part of their sport: “Equal opportunities for men and women are part of triathlon’s DNA, as well as a part of ITU’s constitution.” (World Triathlon, 2016); Nicole Carroll, Co-director of Certification and Training says “It was not part of our culture to even consider that women are not equal or that their performance should not be equally valued.” (CrossFit, 2018).

As more new sports emerge and grow, they will bring about a new idea of equality; it is easy to imagine the outrage that would occur if a sport paid less prize money to men than women for doing essentially the same thing, and nowadays this would also be the reaction to women being paid less than men in a new sport. But for now, it seems that the gender pay gap is a long way from being closed.

References

BBC Sport (2016) ‘Equal pay is as much a myth as it is a minefield’. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/tennis/35863208 (Accessed 20 January 2021).

Billie Jean King (2021) Demanding Change. Available at: https://www.billiejeanking.com/equality/ (Accessed: 26 January 2021).

Boost Power (2021) How long do sports players work for their money? Available at: https://www.boostpower.co.uk/blog/sports-salaries (Accessed: 18 January 2021).

BoxRox (2020) How Much Money Did The 2020 CrossFit Games Top 10 Athletes Win? Available at: https://www.boxrox.com/how-much-money-did-the-2020-crossfit-games-top-10-athletes-win (Accessed: 20 January 2021).

Broadcast Now (2019) Not enough women’s sport on TV, say viewers. Available at: https://www.broadcastnow.co.uk/not-enough-womens-sport-on-tv-say-viewers/5137759.article (Accessed: 20 January 2021).

Bustle (2016) What Women’s Tennis Has Looked Like Through History. Available at: https://www.bustle.com/articles/142759-what-womens-tennis-has-looked-like-through-history-because-women-have-been-part-of-this-sport (Accessed: 26 January 2021).

CrossFit (2018) Why Men and Women are Always Equal in CrossFit. Available at: https://journal.crossfit.com/article/equality-warkentin (Accessed: 26 January 2021).

Desert Sun (2021) No equal pay yet, but women’s golf is adding more prize money. Available at: https://eu.desertsun.com/story/sports/golf/2019/07/09/lpga-majors-continue-increase-their-purses-equal-pay-gets-closer/1676241001/ Accessed: 26 January 2021).

England Rugby (2019) World Rugby Launch Women’s Campaign. Available at: https://www.englandrugby.com/news/article/world-rugby-launch-womens-campaign (Accessed: 26 January 2021)

Forbes (2019) Why Is Serena Williams The Only Woman On The List Of The 100 Highest-Paid Athletes? Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kimelsesser/2019/06/14/why-is-serena-williams-the-only-woman-on-the-list-of-100-highest-paid-athletes/?sh=32725625fa98 (Accessed: 26 January 2021)

Forbes (2021) Highest Paid Athletes in the World 2020. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/athletes/#73e586aa55ae (Accessed: 18 January 2021)

Golf Support (2016) How Big is Golf’s Gender Pay Gap? Available at: https://golfsupport.com/blog/golfs-gender-pay-gap (Accessed: 21 January 2021).

Guardian (2019) We can gauge popularity of women’s football. Time to up the prize money. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/football/2019/oct/22/womens-football-prize-money-world-cup (Accessed: 26 January 2021).

Guardian (2020) FA hits target with 3.4m women and girls playing football in England. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/football/2020/may/14/fa-hits-target-to-double-womens-football-participation-in-three-years-england-gameplan-for-growth#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20women%20and,Gameplan%20for%20Growth%20in%202017. (Accessed: 26 January 2021)

IBC (2020) Sky Sports Aims to Diversify Audiences for Women’s Sport. Available at: https://www.ibc.org/trends/sky-sports-aims-to-diversify-new-audiences-for-womens-sport/5552.article (Accessed: 23 January 2021).

Luxurious Magazine (2020) Six Nations Gender Pay Gap is One of the Worst in Sport. Available at: https://www.luxuriousmagazine.com/six-nations-gender-pay-gap/ (Accessed: 21 January 2021).

Olympic Games (2021) Women at the Olympic Games. Available at: https://www.olympic.org/women-in-sport/background/statistics (Accessed: 26 January).

Tennis Majors (2020) 1968, Open era: The moment tennis opted to become a modern sport. Available at: https://www.tennismajors.com/our-features/long-form-our-features/1968-open-era-the-moment-tennis-opted-to-become-a-modern-sport-228622.html (Accessed 26 January, 2021).

US Open (2018) 50 Moments that Mattered: US Open offers equal prize money. Available at: https://www.usopen.org/en_US/news/articles/2018-08-21/50_moments_that_mattered_us_open_is_first_grand_slam_tournament_to_offer_equal_prize_money.html (Accessed 26 January 2021).

Wimbledon (2020) About Wimbledon: History – 1880s. Available at: https://www.wimbledon.com/en_GB/aboutwimbledon/history_1880s.html (Accessed: 26 January 2021).

Women in Sport (2018) Where are all the women? Available at: https://www.womeninsport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Where-are-all-the-Women-1.pdf (Accessed: 26 January 2021).

World Triathlon (2016) Female participation in ITU races increases. Available at: https://www.triathlon.org/news/article/female_participation_in_itu_races_increases (Accessed: 20 January 2021).