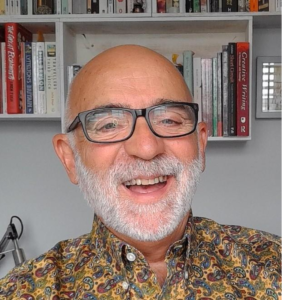

Stephen Tuffin, Associate Lecturer on OU Creative Writing courses A215 and A363, has recently won A Writing Chance bursary – an award that celebrates fresh perspectives and great stories from people whose voices have not historically been heard in publishing and the media. This UK-wide project is co-funded by actor Michael Sheen and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, and supported by the New Statesman and Daily Mirror, with research into barriers to publication being conducted by Northumbria University

We asked Steve to tell us about how his own class background and experience of disability have both helped and hindered his journey into publishing and academia.

I first started writing when I was a road worker. I wrote on bits of paper in the days before PCs. I didn’t write much or very often because much of the time I was too exhausted. The days were very long and very tough.

But, knackered or not, I had this urge to write. I wrote fiction. Short fiction. I didn’t write poetry because I didn’t like it. I didn’t understand it, and, in any case, only posh people read or wrote poems.

Despite not having enough the money, I signed up for the Writers Bureau, and set about learning to write. I paid in instalments, completed several assignments, and was thrilled to receive feedback. But I defaulted on the payments and so was unable to continue. I believe I still owe the Bureau so I’m hoping they don’t read this.

My life took me to Swindon in search of employment. I did a City and Guilds apprenticeship and became a carpenter. I worked on sites all over the place and eventually found myself working at The Institute of Directors in The Mall. I worked there as the lone maintenance man and so found plenty of time to read. I read thrillers and novels about barrel-chested men, with firm chiselled jaws, and women with hour-glass figures and names like Storm. In my spare time, I continued to write. I only ever shared my writing with my wife. No one else. I had trouble with my spelling – and still do.

One day I acquired an electric typewriter – it was being replaced with a new model. I set it up at home and imagined myself to be Hemingway even though I’d never read a word he’d written. I smoked while I wrote. One roll-up after another. I hung doors in the daytime and typed words out at night. Hanging doors is hard physical work but isn’t anywhere near as knackering as digging trenches.

Time passed and the PC came along. Now I could see my words on a screen, as if they were in print, and I could correct my spelling as I went along. I wrote short stories about working-class people – café workers, shop workers, road workers. I wrote what I know.

I fell ill. I was diagnosed with Ankylosing Spondylitis and so my life on site was over. I lost my job, my income and my dignity. I had no idea what I would do next. I considered work in B&Q or as a storeman at the building firm where I’d worked as a carpenter. But my wife had started a course at our local college, and I decided to follow suit.

I wrote my first full length play in the 2002. It was called Roger and Gerald and I didn’t have a clue what I was doing, but I did it. I sat up late into the night and I wrote. I heard their voices in my head, these two men, talking, laughing, arguing, loving. I finished the play and I sat back, and I rolled a cigarette and I felt good.

My college studies took me to Bath Spa University where I gained a BA and an MA in Creative Writing. Later on, I taught there on their undergraduate programme, and it was then that I saw an advert for Associate Lecturers with the Open University. And here I am.

It’s been an interesting journey.

If I am being honest, I’ve always felt a little apart from my colleagues. They are all lovely, but they seem very posh to me. And so much smarter than me, and well educated. In a nutshell, middle-class. And I, well, I was a road worker masquerading as a clever person.

I still am.

I lived too long in that world to suddenly become something else. And I am proud of that world too. I don’t see why, as a working-class man, I can’t enjoy these things that I’ve been led to believe can only be appreciated by the middle-classes. But don’t get me started on that.

You can listen to Martin Sheen read Steve’s work on the BBC’s Margins to Mainstream (about 14 minutes into the programme). This episode also features the work of another awardee, Maya Jordan, who studied creative writing at the OU.

Now I am on this wonderful programme fronted by Michael Sheen for underrepresented writers, and I am seeing my writing take off in a way it never has before.

And the thing is, I have my arthritis to thank for it. So, good things can come in painful packages. Had the AS not got a hold of me I would still be out on site. I wouldn’t be writing this and would never have met all the fine and good people I have taught and worked with over the 16 years I’ve been employed by the OU.

Stephen Tuffin was born in 1958 on a council estate on the south-east coast of England. A former butcher’s boy, cook, cab driver, door-to-door salesman, care home assistant, road worker and builder, he now lives in Swindon and teaches creative writing at the Open University. He is a working-class writer writing working-class stories inspired by the remarkable and raw world he has lived and worked in for most of his life.

Narrative Imperialism and Writing Home: A conversation between Rebekah Lattin-Rawstrone, a new PhD student, and Sarah Butler, a recent graduate

Rebekah Lattin-Rawstrone has just embarked on a PhD in creative writing funded by the Open-Oxford-Cambridge Arts and Humanities Research Council Doctoral Training Partnership. We put her in touch with Sarah Butler, who was recently awarded her own PhD in creative writing, which was also funded by the AHRC – in her case via the Consortium for the Humanities and the Arts South-east England. Here, Rebekah and Sarah let us eavesdrop on their conversation about their writing and research.

Sarah Butler

Rebekah Lattin-Rawstrone

Rebekah: It’s a privilege to be given this chance to focus for three whole years on something that really fascinates me – narrative imperialism in the contemporary British novel. But that privilege brings responsibility with it.

Sarah: I’d love to hear more about the concept of narrative imperialism.

Rebekah: This gets right to heart of what I’m hoping to explore in both my critical writing and in the novel. I intend to unravel this concept from several angles: firstly, looking at the development of the novel during a time of imperialism and asking if that affected the narrative structures widely adopted in the form, particularly the three act teleological structure based around conflict and resolution; secondly, building on feminist criticism of narrative structures, thinking specifically of Ursula K. Le Guin’s wonderful essay ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’ in which she outlines the possibility of new story forms that don’t follow the spear, or the arrow model – the hero’s journey model – but the gathering, containing, holding model, arguing that the bag rather than the stick was the first human tool; thirdly, looking at the wide adoption in the creative writing industry, both academic and commercial, of the three act structure and the hero’s journey, especially under the influence of film theory, and asking whether, as the industry attempts to publish different stories it could also look for writing that tells these stories differently (put in another way, are we only interested in different stories when they fit into a certain story telling structure? Are we continuing to enforce a kind of narrative imperialism?).

Sarah: This is so interesting! I teach creative writing at Manchester Metropolitan University and have been reading critiques of the workshop model by writers coming from different literary/cultural traditions. I’ve been thinking about the assumptions I make about structure and form, and about how I support writers and writing from backgrounds different to my own.

I set off on my PhD thinking I was going to write about narrative and ageing and particularly about endings and death, but very early on in the process my supervisors asked me to ‘just write something’ reflective about my work. I ended up writing an essay about home across all of my published work, and realised that it is a huge and pressing theme for me.

Rebekah: I read your response with real delight because the concept of home has been a driver for my work too. I was born overseas and my father then became a diplomat so I spent a lot of time abroad as a child and it has had a huge impact on how I think about where and what I call home and how that might relate to a sense of belonging. You can see how all of these things then fed into an interest in world literature and a wider storytelling practice.

My first novel is actually called Home. It is about a corrupt care home, and I was trying to explore the fractures in the English extended family unit. Age, death and home – more common themes with you. My second novel is about a white English woman trying to forge a relationship with her Malawian half-sister. The desire to create a sense of family and home across national boundaries is central to this book.

I’ve begun by investigating possible alternative narrative structures and am having a lot fun looking at Islamic architecture and the mathematics of tessellation as a possible model for my novel’s structure. As the novel is partly set in Iraq, there is a real wealth of early literature to draw on. It makes for an interesting contrast with my protagonist, real-life adventurer Gertrude Bell who, as someone very keen to contribute to world events, did her best to fulfil the hero’s journey – albeit the heroine’s journey. I’m interested in her life outside of the public eye and how what often really fulfils us in life isn’t always our achievements. In that way, both the subject of the story and the telling should cohere as they attempt to express something different to the traditional three act structure. There will be other threads to the novel too, adding to that sense of pattern and structure through tessellation.

Sarah: I am a bit obsessed about applying structures from different disciplines/places onto writing, so I love the idea of taking ideas from architecture and maths and using those to find a structure for your novel. The way the form and the content are working together also sounds fascinating (and very satisfying!). It’s also really interesting to me because I have an idea for a new novel that I’m struggling to impose a traditional structure onto – I feel as though this conversation has given me permission to think that might not be such a bad thing!

When I started out on my PhD, I worried that ‘over’ analysing my own work would somehow damage my creative process. In fact, it’s been just the opposite. Spending time really thinking about my themes and process has given me a certain clarity of purpose. It’s allowed me to be clearer about what I’m interested in and what I want to explore in my writing.

I’ve been doing some research work for some academics at the OU about the climate crisis and creativity and that’s got me thinking about how I might combine my interest in home with my concern about the climate crisis. I guess I think of myself as both a writer and a researcher now, and that feels exciting and full of possibility.

I wish you all the very best with your PhD. It sounds fabulous, and important, and I am sure it will be an adventure worth having!

Rebekah Lattin-Rawstrone is the author of short story collection Glitches (Acorn Publishing, 2014) and novel Home (Red Button, 2015, now Kindle Direct Publishing). The working title of her PhD is Longing to Belong: an investigation into the potential for alternative storytelling techniques, in particular from the Middle East, to challenge narrative imperialism in the contemporary British novel.

Twitter: @RebekahLattinR; Website: www.lattin-rawstrone.com

Sarah Butler is the author of novels Ten Things I’ve Learnt About Love (Picador, 2013), Before The Fire (Picador, 2015) and Jack and Bet (Picador, 2020). The title of her PhD is Writing Home: an exploration of the writing of Jack and Bet (a novel) and a consideration of what the novel – as a space and a practice – offers to our understanding of the concept of home, and what a consideration of home offers to our understanding of the novel.

Twitter @SarahButler100; Insta: sarahbutlerwriter; Website: http://www.sarahbutler.org.uk/